Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Osong Public Health Res Perspect > Volume 11(4); 2020 > Article

-

Review Article

COVID-19: Weighing the Endeavors of Nations, with Time to Event Analysis - Shine Stephen, Alwin Issac, Jaison Jacob, VR Vijay, Rakesh Vadakkethil Radhakrishnan, Nadiya Krishnan

-

Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives 2020;11(4):149-157.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.4.02

Published online: August 31, 2020

College of Nursing, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, India

- *Corresponding author: Shine Stephen, College of Nursing, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India, Email: shinestephentn@gmail.com

Copyright ©2020, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Abstract

- The cataclysmic COVID-19 pandemic erupted silently causing colossal impact worldwide, the repercussions of which indicated a lackadaisical vigilance in preparation for such a pandemic. This review assessed the measures taken by nations to contain this pandemic. A literature review was conducted using Medline, Google Scholar, Science Direct, Scopus, and WHO website. There were 8 nations (selected from the GHS index list) appraised for containment strategies. This was achieved by using mortality rate (per million) as the primary endpoint. The nations which were proactive, initiated scientific strategies earlier with rigor, appeared to have succeeded in containing the pandemic, although it is still too early to arbitrate a verdict. The so called “pandemic war” mandates international, interdisciplinary, and interdepartmental collaboration. Furthermore, building trust and confidence between the government and the public, having transparent communication, information sharing, use of advanced research-technology, and plentiful resources are required in the fight against COVID-19.

- Corona Virus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) has spread to most nations. Migration, climate change, urbanization, and international mass displacement are some prevailing factors that are ideal for a virus to cause a pandemic [1]. The initial infection was reported in Wuhan, China in late 2019, and rapidly spread worldwide thereafter [2]. On March 11th 2020, based on “alarming levels of spread and severity, and a worrisome level of inaction,” COVID-19 was announced as a pandemic by the Director-General of World Health Organization (WHO) [3]. Screening, surveillance, quarantine, lockdown, testing, isolation, and treatment were the approaches adopted by most nations to contain the pandemic. Some nations prudently executed most of these approaches early, whereas, some nations precariously delayed implementation and the outcomes have been very discernible, although it may be too early to arbitrate the success of these strategies. Fluctuations in the number of tests, positive cases, and case fatality rate (CFR) are the probable outcomes of a country showcasing their preparedness and timely containment measures.

- This article aimed to examine COVID-19 containment strategies for nations which rank highly in the Global Health Security (GHS) index. The GHS index was a joint project of the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, and was developed with the Economist Intelligence Unit. The GHS index ranked 195 countries based on their health security, preparedness against epidemics, and related capabilities. Interestingly, the 8 nations selected for this review were amongst the top ranked countries of the GHS index, however, their performance and outcomes for COVID-19 containment measures were incongruous with their respective GHS index scores.

- The toll of COVID-19 positive cases and deaths are escalating swiftly and the current situation drives each nation to learn from the successes and failures of other countries during this pandemic.

Introduction

- A thorough literature search was performed to retrieve the containment strategies of the selected nations between January and July 2020, using Medline, Google Scholar, Science Direct, Scopus, and the official websites of the WHO and the concerned nations. The keywords were COVID-19, pandemic, SARS-CoV-2, preparedness, and containment strategies. Amongst the nations that are ranked in the top 10 of the GHS index, 8 countries (United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Thailand, Sweden, South Korea, and Finland) were selected, all of which reported index cases of COVID-19 in January. Available data from these countries included COVID-19 cases (date of index positive case, number of tests performed, number of positive cases, and deaths), mitigation (availability of human resources, personnel protective equipments arranged, number of hospital beds including critical care beds with the facility for mechanical ventilation and other strategies) and response (screening and isolation facilities, implementation of lockdown, public relations, and restricted travel). Since mortality is a precise appraisal of the progression and outcome of a pandemic [4], with which the management strategy of a nation can be evaluated, the death rate (per million population) was fixed as the primary endpoint for evaluating the outcome of measures taken by these 8 selected nations.

- 1. Containment strategies: uniqueness, versatility, and outcomes

- According to the WHO, all individuals who had come in contact with a COVID-19 positive patient needed to be in quarantine for a fortnight (incubation period of COVID-19), starting from the last day they had contact with the patient [5]. Those infectious would be isolated (to curb further spread) and social distancing (more than 1 meter and no group gathering) norms would be followed.

- In the United States (US), a returnee from Wuhan tested positive for COVID-19 on January 20th. A surge in the number of patients was observed initially due to the delay in commencement of COVID-19 testing [6]. Many of the testing kits developed by the US were reported to be erroneous [7]. On January 29th, the White House coronavirus taskforce was set up to organize and oversee efforts to contain and palliate the spread of coronavirus in the US. Two days later, a public health emergency was declared, which barred entry to foreign nationals who had visited COVID-19 affected nations (China, Iran, United Kingdom, Ireland, or the 26 European countries) in the past 2 weeks. US nationals returning home after travelling through COVID-19 affected countries had to undergo a compulsory health screening and be quarantined for a fortnight. Non-essential travel to COVID-19 affected nations was banned, yet a nationwide lockdown was not imposed. A national emergency was announced on March 13th [8]. By April 11th, all public events were cancelled and schools were closed (Figure 1).

- On January 31st, the first case of COVID-19 was reported in York, England, in an infected Chinese national. As soon as the case was confirmed, a public health information campaign that resembled a previous “Catch it, Bin it, Kill it” campaign was initiated, to educate the public on reducing the risk of spreading the virus [9]. Public Health England (PHE) was slow to enact action. Though most countries focused on “containment policy,” the UK was led by the scientists to believe in “herd immunity” and the control measures appeared not to be stringent enough. Schools were all shut down by March 20th (Figure 1). The Coronavirus Act 2020 was enacted by government on March 19th, which offered discretionary powers to the government in areas of schooling, health care organizations, border force, and courts. The UK was forced into lockdown on March 23rd due to a drastic increase in the number of cases [9].

- Australia reported its first case on January 25th. On the 13th February, the government barred entry of tourists arriving from mainland China, and advised returning residents to self-quarantine for a fortnight upon arrival, and warned that noncompliance would warrant a fine. On March 15th the National Cabinet announced that gatherings of more than 500 people should be called off with exceptions for schools, universities, workplaces, and public transport [10]. An overseas travel ban was imposed on March 20th (Figure 1) and cruise ships were barred from docking in ports. Owing to a lackadaisical approach towards COVID-19 management, cases began to rise in mid-March. Australia’s stockpile of personal protective equipment (PPE) wasn’t sufficient to meet the demands and later the country ran out of PPE. Initially, only people returning from overseas or those who had come in contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case were tested. This proved insufficient, and they expanded their testing to the vulnerable, health care workers, anyone exhibiting mild symptoms of COVID-19 and even asymptomatic cases [10].

- A human bio-security emergency was declared on March 18th owing to the hazard to human health caused by COVID-19, and stringent measures were imposed with the shutting down of non-essential services, urging vulnerable people to stay indoors, social distancing rule of 4 square meters per person in an enclosed space (which was later modified to include only 2 people who could meet in public places). People were permitted to go outdoor to purchase essential items, for medical or humane needs, exercising (in line with the limitation of 2 people meeting in public), and for job or educational activities. A mobile application (app) “COVIDSafe” that uses Bluetooth technology was developed to show contact between people when they come within 1.5 meters of each other [11].

- The index case for Canada’s COVID-19 epidemic was reported on January 27th, in Toronto. A stringent border access ban was put in place and the Quarantine Act was invoked that warranted all persons (excluding essential workers) entering the country to self-isolate themselves for a fortnight, prohibited those with symptoms from using public transit, and barred self-isolation in settings where they may come in contact with vulnerable people [12]. Global Affairs Canada provided consular support to Canadians stranded in other countries affected by COVID-19 and numerous educational resources about coronavirus management were circulated amongst the public. International passenger flights were allowed to land only in 4 designated airports to ensure vigilant and coordinated screening of the passengers [13]. The government believed that broader testing was the key to reopening the country and thereby paced their testing capacity through an interim order. The Federal government activated their emergency operations center on January 15th, and the Government's pandemic response was based on the Canadian pandemic influenza preparedness planning guidelines and the Federal/provincial/territorial public health response plan for biological events [14,15]. On March 12th the government ordered the shutdown of schools (Figure 1), bars, restaurants, cinema halls, non-essential businesses, and public gatherings; community transmissions were reported by mid-March, which forced the country to declare a state of emergency (Figure 1) [13]. Canada, having a universal health care system, enabled the public health authorities to commandeer the hospital system. A smart-phone app that notifies the users if they have been in the proximity of a person who has tested positive for COVID-19, will be launched in July [13].

- Even before Thailand reported their initial COVID-19 case, passengers from China were screened at the airports. Thailand was the first country to report a COVID-19 case outside China. On January 8th, a Chinese tourist who had flown from Wuhan to Bangkok (Thailand) was identified using thermal surveillance and tested positive for COVID-19, 4 days later [16]. Owing to the nation’s weaker economy, mass screening was not affordable and so contact tracing was initiated early. On January 23rd, the government issued a decree barring all non-essential travel to China, and a curfew was imposed from 10 pm to 4 am. By mid-March all non-essential businesses were shut down along with schools, entertainment venues, and public gatherings were barred (Figure 1). On April 4th international flights were denied entry into the country (Figure 1) except for those bringing Thai citizens from abroad. Travelers had to be quarantined for a fortnight in a government-managed setting. It was mandatory that every person entering a shop or restaurant scanned a quick response (QR) code using their phone, which later facilitated contact tracing as deemed by the situation. Thai administration employed village health workers who supervised people’s movements in and out of their villages, carried out domicile visits (to monitor people’s temperature, communicated health messages about COVID-19, and how to prevent it, and documented household health data), and conveyed data to the provincial health office and the central government. While the government declared a state of emergency, the fight against the pandemic was driven by public health authorities deploying a policy of prompting people to use face masks, hand sanitizers, practice social distancing, and staying at home. Visual and audio reminders were omnipresent in public places and shopping centers [17]. Culturally transmitted norms of personal hygiene, voluntary abidance to government recommendations, volunteers from hundreds of thousands of grass-root public health activists, and collaboration among the public health authorities, paved the way for their success at keeping COVID-19 transmission to a minimum [18]. By mid-June the country had resumed its normalcy, though preventive measures such as wearing a face mask, and social distancing were still being followed.

- Sweden is a prominent country in Europe that marked a stable performance in human development and quality of life indices and ranked highly in the GHS top 10 index, with a population of nearly 10.3 million. The country registered its maiden COVID-19 case on January 31st in a woman returned from Wuhan city, and the second positive case was reported nearly a month later.

- On February 17th, the government put a travel ban in place to Hubei province and advised against non-essential travel to grossly affected nations [19]. The public health agency of Sweden was entrusted to advise and monitor the action plan to contain virus spread. The primary aim was to curb the spread of COVID-19 to limit the demand on the health services, such that it didn’t overwhelm the country’s hospital capacity. General containment strategies were employed where social distancing was advised for vulnerable people especially the elderly, and people with respiratory illness were told to isolate. There was no nationwide lockdown in Sweden because the government was not eager to curb movement for their citizens. Secondary schools and universities were closed on March 17th, however primary schools were exempted from shut down. On March 11th the government passed a law banning gatherings of more than 500 people, and later reduced the number to a group of 50 people on March 27th as the case numbers surged. Since early March 2020, the government held a daily press conference to empower the public with advice and recommendations to contain the virus spread, and by March 18th an advisory travel ban was imposed within the country. Testing for COVID-19 started in January, however, the number of tests (per 100,000 population) conducted was lower than many other European countries, and was limited to those who were symptomatic or citizens returning from COVID-19 affected regions. The testing capacity was escalated gradually and peaked to 30,000 tests per week towards mid-May and contact tracing was optimized [19]. The public health agency was entrusted with full control over the COVID-19 response strategy (without much interference from government and political pressure) which made the Swedish response unique compared with other nations.

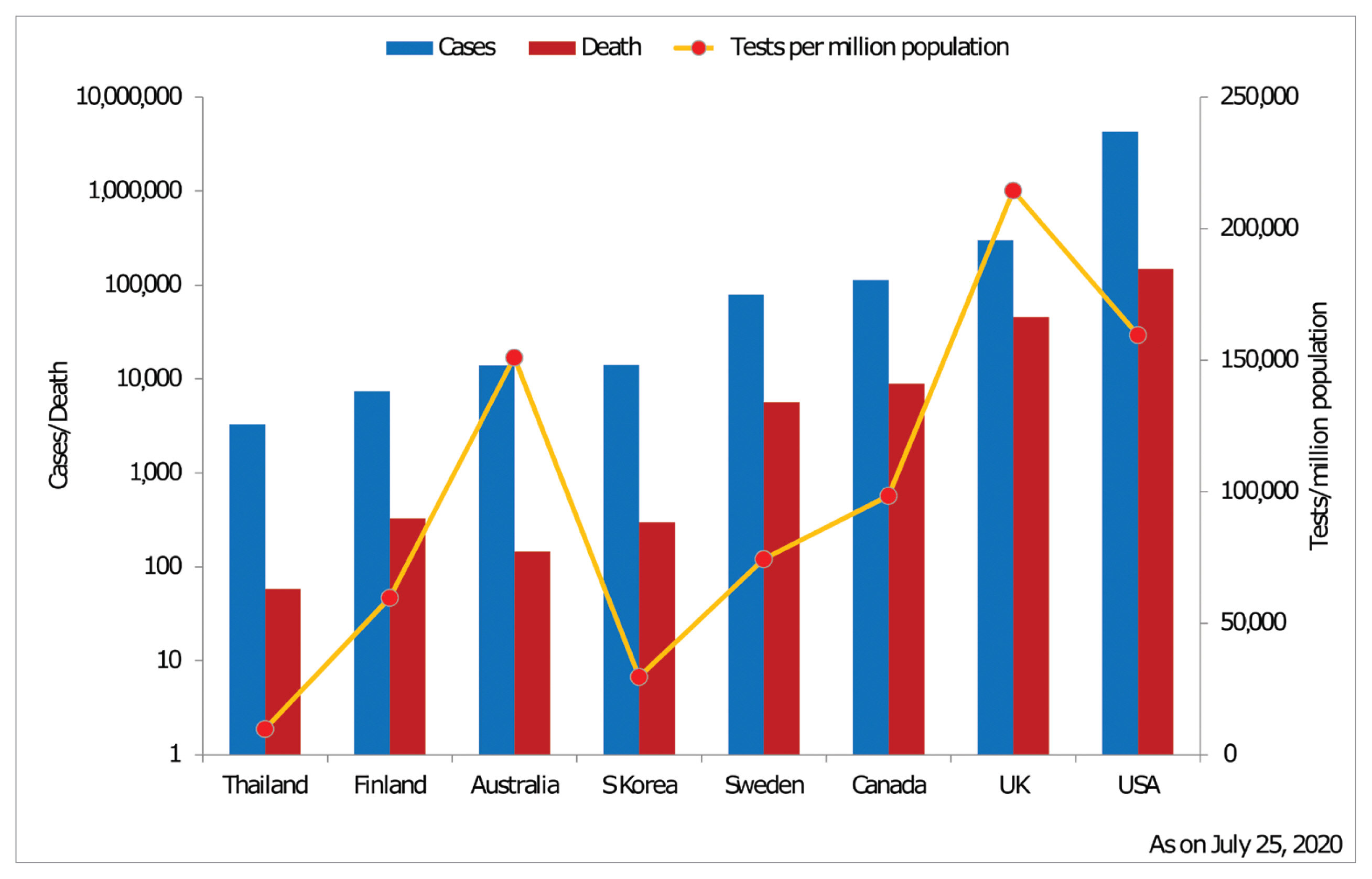

- A 35-year-old Chinese woman tested positive for COVID-19 on January 20th in South Korea [20]. Korea’s response was 4-pronged: test, track, trace, and treat. Testing was not limited to symptomatic patients or those from the afflicted regions, even asymptomatic people were tested. Owing to the high proportion of cashless transactions, phone ownership rates, and density of surveillance technology, health officials retraced patient’s movements using security camera footage, credit card records, and GPS data from their cars and cell phones [21]. A travel ban was imposed to affected countries, a partial lockdown in Daegu (the city which was affected the most), and shutdown of educational institutions were in place by February 19th (Figure 1). Drive-through testing centers were functional by March 13th. Soon after the virus was isolated in China, Korea Centers for Disease and Prevention (KCDC) produced testing kits (100,000 kits per day) and conducted 29,619 tests per million population (Figure 2). A local surveillance team called in twice a day to ensure the traced person remained isolated, and even people with mild or no symptoms were isolated [22]. Under the relevant acts of government, the ministry of health collected personal data of COVID-19 confirmed and possible patients. Face mask use was commonly observed by the public. Simultaneously, the country permitted the public a “right to know” the movements, conveyance means, and links of patients which in turn helped them to avoid hotspots of infection [23].

- Finland reported their index case when a Chinese woman who traveled from Wuhan to Finland tested positive on January 29th. At a time when other nations struggled to keep a steady supply of personal protective equipment, Finland had an enviable stockpile of medical supplies amassed during the Cold War era. While every other nation had not stockpiled supplies, Finland was prepared for the heightened demand for medical supplies, and this proved to be pivotal in the country's, response to COVID-19 [24]. The country limited its coronavirus testing capacity to the most vulnerable and health care personnel. A state of emergency was declared in the country on March 16th, and various measures were imposed to slow down the spread of virus and protect at-risk groups under various acts of the country. This included shutting down schools (excluding early education), a ban on public gatherings and closing government-run public facilities (Figure 1). The border with neighboring nations was closed on March 19th [25]. Test, trace, isolate, and treat, besides stepping up other prohibitory measures in a contained manner, were the strategies adopted by the nation [26].

Materials and Methods

1.1. United States

1.2. United Kingdom

1.3. Australia

1.4. Canada

1.5. Thailand

1.6. Sweden

1.7. South Korea

1.8. Finland

- Much evolved state-of-the-art technology aided expeditious identification of the novel coronavirus and updated the information to the entire globe. Novel technology merged with conventional methods, case detection, isolation, contact tracing, quarantine, and infection control measures were employed to counter the pandemic. It’s too early to judge the efficacy of measures taken by different nations, although a few countries kept the pandemic in check. Control measures executed by the nations scrupulously resemble each other and are in accordance with the WHO recommendations.

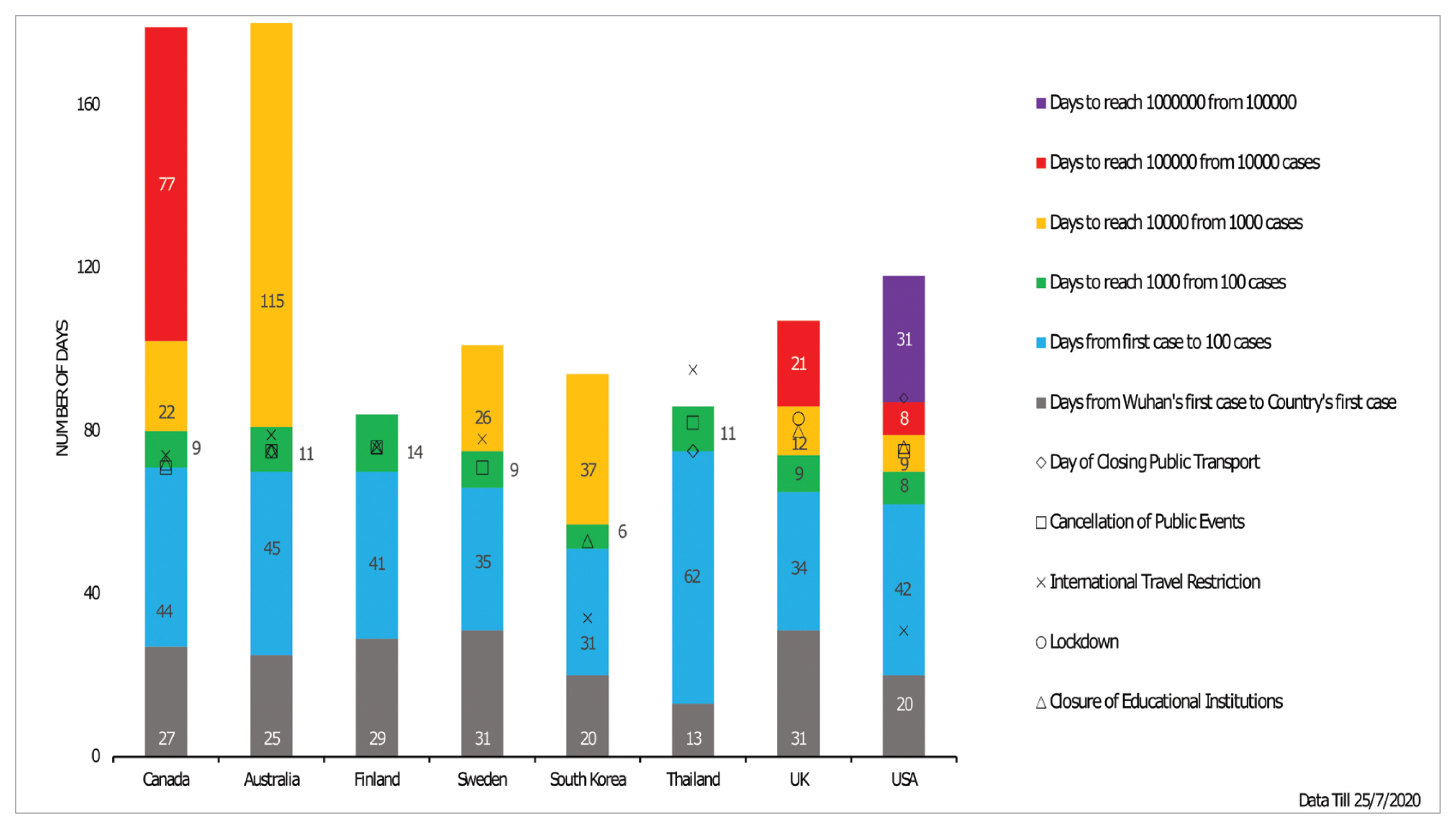

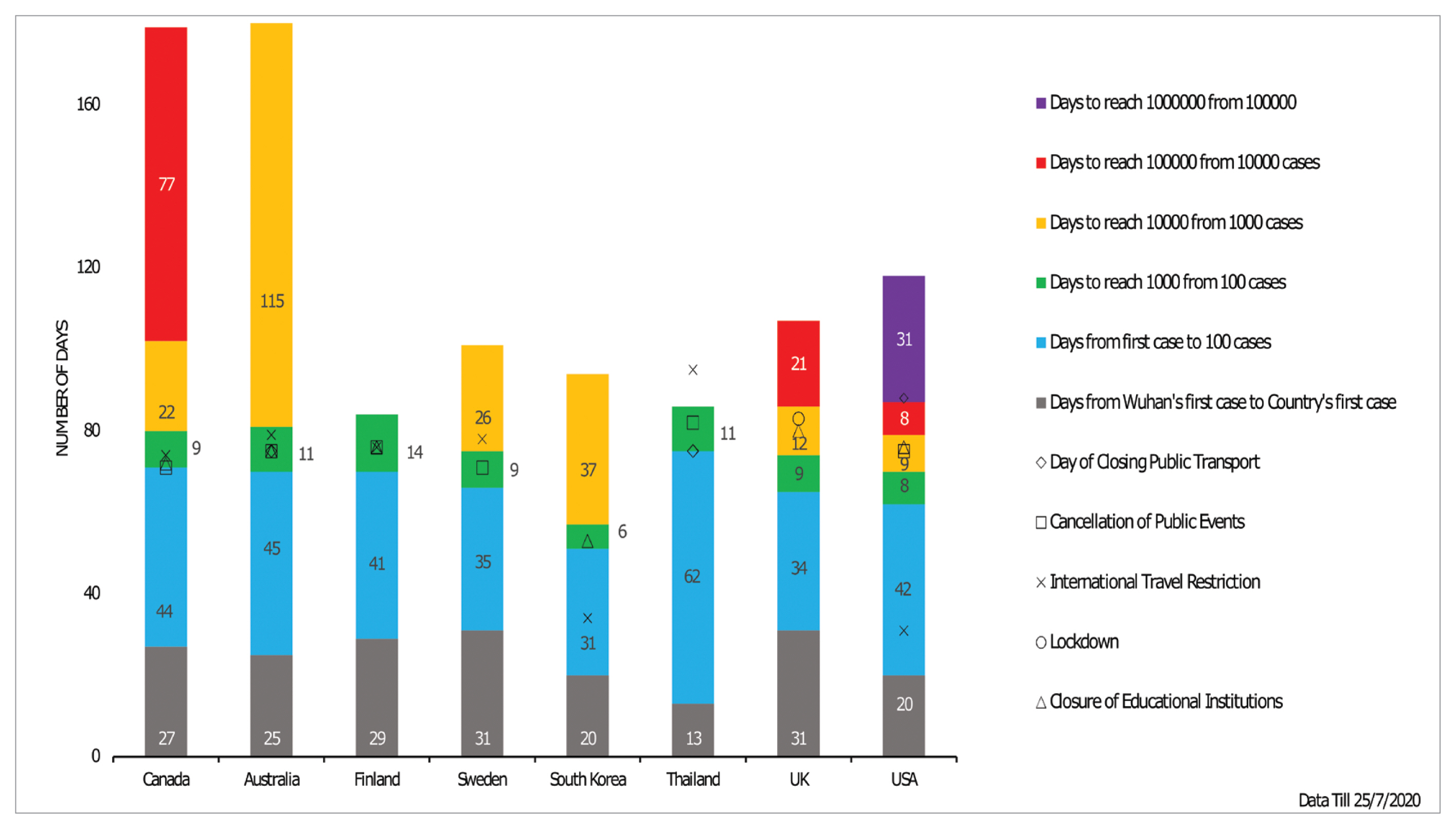

- It is imperative to note that COVID-19 transmission occurred across nations at varying timelines depending on the connectivity, initiation of early mitigation measures, trade relations, deployment of containment strategies, and various socio-behavioral aspects. As depicted in Figure 1, Thailand, South Korea, and US registered their index COVID-19 case 13 to 20 days after the Wuhan outbreak, owing to their close trade relations with China. Whereas European countries took almost a month to have their maiden case. Thailand took 62 days to mark its 100th case from the index case while other nations crossed the same benchmark between 31 to 45 days. Importantly, South Korea and the US employed early international travel bans long before their 100th case. The initial transmission was rapid in the US and UK as it took less than 10 days to reach the national toll to 1,000 cases from the 100th case, while other nations took nearly 2 months. Though it took less than 2 weeks for every nation to record the 1,000th case from the 100th case, Australia and South Korea required 115 days and 37 days to reach 10,000 tallies from the 1,000th case, whereas Thailand and Finland have still not crossed the 10,000 mark, reflecting tightened reigns over the disease spread.

- The early grip for these nations can be attributed to their swift border closures and travel restrictions, suspension of educational institutions, closure of public events, and meticulous testing and contact tracing from an early time point. The nations like US, UK, and Canada needed just 9, 12, and 22 days respectively to climb 10,000 cases and witnessed an exponentially rapid spread in the following days. Notably, the US and UK delayed the implementation of stringent lockdowns, a public transport ban, and event cancelation compared with other nations, which later proved fatal. However, the UK and Canada managed to regain control over the spread of disease, while the US succumbed to COVID-19 and witnessed over 4 million cases and is still facing an active pandemic.

- Cases in the US have skyrocketed suggesting the inefficiency and flaws in their pandemic management strategies. The US dominates globally with a case toll of more than 4 million (Figure 2). The lack of previous experience in managing viral outbreaks (e.g., Zika, Ebola, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) has led the US not being prepared. Regardless of the availability of the virus genomic sequence from January 11th, the US failed to produce enough testing kits. Rather, many of the available testing kits proved to be defective. There was no specific testing strategy, which might have led to many probable cases being missed. Insufficient supply of personal protective equipment for health care providers also worsened the situation. The assumption that only the aged and vulnerable population were at risk also proved to be fatal [27] with a mortality of 450 per million population (Table 1). The approach of viewing COVID-19 like a seasonal flu, despite medical knowledge warning to the contrary, proved detrimental [28] with the lowest recovery response (RR) among the nations studied in this review of 8 countries in the top GHS index (47.57%; Table 1). Ignoring ominous signs, the US administration focused on saving the economy rather than saving lives [29]. Having a decentralized public health system, coordination became arduous and early advisory warnings from nodal agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were not heeded. All of these factors made for a chaotic situation.

- Even though the UK ranked 2 in the GHS index, the response towards COVID-19 was questionable. Having a National Health Service, stringent action plans against COVID-19 were not enacted, which attributed to a swift surge in cases by the end of March. Though the UK developed specific laboratory tests and coronavirus action plans to combat the disease, its implementation was delayed and overwhelmed the National Health Service with a case toll of 298,681 and a death toll of 674 per million population as on July 25th (Figure 2). Non-adherence to the “track and trace” instructions (of WHO to identify and isolate cases), a limited PPE supply to health care workers, implementation of late lockdown, and unorganized testing added to the surge in case toll. There was no effective system to report recovered cases [30]. The CFR of 15.4 % (Table 1) showed poor COVID-19 containment in the UK [31].

- Australia displayed commendable efforts to tame the viral spread to a state of single-digit cases per day since its index case in late January, though it’s now battling with a second wave of disease transmission. Early success in taming the outbreak was not only due to early closure of national borders, social distancing, quarantine and contact tracing of the infected, and cancellation of public events, but also partly attributed to transparent information sharing, escalated approach of imposing restrictions, swift testing of suspected infection cases and their contacts, and all high-risk individuals in hotspots. The government also focused on safeguarding economic ventures to continue business and released economic stimulus packages to their citizens. Importantly, the nation’s CFR was 1 out of 13,948 infected (Table 1) which is well below the global average reflecting another facet of containing the pandemic in long run. The key to Australia’s success at reducing COVID-19 transmission was attributable to its public acceptance of spatial distancing and wide access to tele-health.

- Canada couldn’t protect their elders in long-term care which increased their CFR (7.9%) and diminished RR (87.31%; Table 1). A report by the Royal Society of Canada reported COVID-19 as a “shock wave” which revealed numerous long-standing deficiencies in the health care system which grossly affected their senior citizens [32]. Access to primary health care was limited due to the shortage of registered nurses and other health care facilities. The government had to recall retired medical practitioners to meet the increased health care needs of the country [33]. If a system of early warnings about the pandemic was in place, they could have brought the situation under control [34].

- Thailand’s centralized level of governmental administration made it easy to enact rules regarding the containment of an epidemic. The role played by employed village health volunteers in containment and mitigation measures was commendable. Moreover, Thai citizens adhered to governmental advice regarding the pandemic. Recent data showed that about 95% of Thais wore masks during the epidemic, which is highest in Southeast Asia [35]. All these measures facilitated the containment of the epidemic which resulted in a case toll of 3,282 and CFR 1.8% (Table 1) despite being the first country to report a COVID-19 case outside China.

- With the 7th position in the GHS index, Sweden followed a unique way of dealing with COVID-19. Instead of complete lockdown, limited movement restriction was imposed. The public maintained social distancing [36]. The death per million population in Sweden was 564 (Table 1), which is quite high compared with similarly GHS index ranked nations. The healthcare capacity in terms of bed numbers and infrastructure was far lower than other developed countries. The health care system focused on protecting the aged and the vulnerable population to reduce the spread of the virus, but this was ineffective in safeguarding the nation. The focus was to prevent over congestion of the health care system. Due to the congested healthcare system, the citizens with symptoms had to stay at home, which augmented fatalities. The way Sweden dealt with the epidemic invited much criticism from many corners of the world [19].

- South Korea’s response proved that they were well prepared for the epidemic even though it ranked 9th in the GHS index. The screening program for COVID-19 was initiated well before the reporting of its index case. Mass testing was planned and executed along with large scale production of testing kits. Effective contact tracing was carried out using digital technology. Timely implementation of drive-through screening centers, widespread use of masks, and testing of asymptomatic individuals made Korea free from community transmission of COVID-19. 1 in every 100 citizens were tested, which was a high benchmark whilst combating COVID-19. The administrator’s accuracy in data sharing of the key features of the outbreak prevented ambiguity and confusion among the public. Moreover, Korea had formal standard operating procedures to be followed regarding the containment of epidemics [37]. These measures helped them to limit the number of cases to 14,092 with a commendable recovery response (RR) of 91.30% [33] (Table 1).

- Finland relied on a hybrid strategy to contain the virus spread which ensured normal living while still employing containment measures. The disease curve flattened from the early weeks of April which initiated the gradual lifting of imposed restrictions including travel bans, re-opening educational institutes, and business endeavors to minimize public life and economy from succumbing to the pandemic. Reciprocal support between the public and private sectors to prepare and stockpile the needed supplies and equipment for health care helped them in this emergency. The nation’s strong base in numerous human development indices, and timely streamlined containment strategies, coupled with strong legislation from governmental agencies, along with public support flattened the outbreak curve in April 2020, with 7,388 cases as of July 25th in a population of nearly 5.6 million. The Finnish strategy highlights the need to balance the containment measures for disease outbreak and national sentiment. They brought the pandemic under control with the highest RR of 93.67% among the nations studied (Table 1).

- SARS-CoV-2 infection, which was initially thought to be spread through contact, is now proved to be disseminated by airborne droplets, although the complete picture is still evolving [38]. The threat posed by the viral disease escalated and triggered global solidarity to work towards a definitive treatment regime or vaccine [39]. To date, no specific treatment or clinical guidelines proved effective despite several randomized clinical trials, where efforts are continuing. Furthermore, numerous pharmaceutical companies and national laboratories are in the process of vaccine development which are in various stages of development and testing, with none approved for prophylaxis. As a general agreement, a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is the ultimate solution to reduce the mortality and morbidity associated with the disease [40].

- 1. Lessons from well-controlled nations

- Most of the nations followed traditional measures of containment of an epidemic including screening, surveillance, quarantine, lockdown, testing, and isolation. Some nations prudently executed them earlier, whereas some delayed and the outcomes are very discernible, although outcomes of these strategies will be measured over time.

- Transparency in sharing the available information related to the disease outbreak and related epidemiology, widespread testing of suspected cases and contacts assisted the Australians to flatten the disease curve. Coordinated efforts by the health workers, responsible public actions, and centralized rules enactment by the Thailand administration facilitated them to curb the spread of infection. The MERS outbreak of 2015 enabled South Korea’s development of standard operating procedures to be followed during an epidemic. Their widespread testing and effective case isolation helped to bring the infection under control. Coordinated efforts through public-private partnerships at different phases of containment along with citizen cooperation aided a low rate COVID-19 infection in Finland.

- 2. Modifications and reformations for future pandemics

- Biological threats like the COVID-19 pandemic are inevitable and every nation must expect them to pose a great challenge to global health and security. There is an alarming need for every nation to be prepared and capable to swiftly respond to such public health emergencies. Confidence needs to be provided to neighboring countries that the outbreak can be prevented if there is a future global pandemic. Moreover, world leaders and international agencies must bear a collective responsibility to ensure a coordinated response.

Each country should develop health intelligence teams capable of giving early warning of a health emergency.

Epidemic preparedness plans and standard operating protocols for each nation should be designed and updated periodically.

Policies for judicial use of available resources during a disease outbreak should be developed and implemented.

Measures to gain the confidence of the public, like transparent information sharing to be established.

Centralized administration to monitor and oversee sustainable action plans during a disease outbreak is crucial to coordinate national efforts.

Recruitment, pre-preparedness, and continuous training of the workforce for epidemic/pandemic control.

Investing more in infectious disease prevention, control, and related research.

Developing precise and sophisticated technology in surveillance, control, and preventive methods.

- Limitations of this review are that it did not address the preparedness of nations and the factors associated with mortality of COVID-19. However, this was a meaningful appraisal about top-rated GHS index nations handling of the COVID-19 epidemic across key containment and combating strategies.

Discussion

- The measures different countries adopted for COVID-19 were similar, but their timing and rigor in implementation made a huge impact upon how the country fared concerning case fatality per head of population. Although the picture is still evolving, and no country was fully equipped to respond to COVID-19, countries with a centralized and government-dominated healthcare system responded better in terms of adapting to absorb the surge in cases, provided the response was guided and backed by well-timed political will. Moreover, early implementation of stringent containment strategies have reduced transmission rates in many countries.

Conclusion

- 1. 2019-Global-Health-Security-Index.pdf [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 8]. Available from: https://www.ghsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019-Global-Health-Security-Index.pdf.

- 2. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054−62. PMID: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. PMID: 32171076. PMID: 7270627.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Press briefings [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/media-resources/press-briefings.

- 4. Zylke JW, Bauchner H. Mortality and Morbidity: The Measure of a Pandemic. JAMA 2020;324(5). 458−9. PMID: 10.1001/jama.2020.11761.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Considerations for quarantine of individuals in the context of containment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/considerations-for-quarantine-of-individuals-in-the-context-of-containment-for-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19).

- 6. Wang J. [Internet]. How the CDC’s Restrictive Testing Guidelines Hid the Coronavirus Epidemic [Internet]. The Wall Street Journal 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 6]. Available from: http://archive.vn/tp9HA.

- 7. Kenen J. [Internet]. How testing failures allowed coronavirus to sweep the U.S. Politico 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.politico.com/news/2020/03/06/coronavirus-testing-failure-123166.

- 8. Official Guide to Government Information and Services | USAGov [Internet]. [cited 2020 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.usa.gov/.

- 9. Department of Health & Social Care [Internet]. Coronavirus action plan: a guide to what you can expect across the UK GOV.UK; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-action-plan/coronavirus-action-plan-a-guide-to-what-you-can-expect-across-the-uk.

- 10. Prime Minister of Australia [Internet]. Update on coronavirus measures [cited 2020 Jul 19]. Available from: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/update-coronavirus-measures.

- 11. Attorney-General's Department, Australian Government [Internet]. COVIDSafe legislation [cited 2020 Jul 19]. Available from: https://www.ag.gov.au/rights-and-protections/privacy/covidsafe-legislation.

- 12. Dunham J. [Internet]. Travellers returning home must enter mandatory isolation: health minister. Coronavirus 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 18]. Available from: https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/travellers-returning-home-must-enter-mandatory-isolation-health-minister-1.4867749.

- 13. Government of Canada [Internet]. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Canada’s response 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 18]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/canadas-reponse.html.

- 14. Government of Canada [Internet]. Federal/Provincial/Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events 2018 [cited 2020 Jul 18]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/emergency-preparedness/public-health-response-plan-biological-events.html.

- 15. Government of Canada [Internet]. Canadian Pandemic Influenza Preparedness: Planning Guidance for the Health Sector 2006 [cited 2020 Jul 19]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/flu-influenza/canadian-pandemic-influenza-preparedness-planning-guidance-health-sector.html.

- 16. Cheung E. [Internet]. Wuhan pneumonia: Thailand confirms first case of virus outside China. South China Morning Post 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/3045902/wuhan-pneumonia-thailand-confirms-first-case.

- 17. Bello W. [Internet]. How Thailand Contained COVID-19 - FPIF. Foreign Policy Focus 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://fpif.org/how-thailand-contained-covid-19/.

- 18. Department of Disease Control [Internet]. Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) [cited 2020 Jul 18]. Available from: https://ddc.moph.go.th/viralpneumonia/eng/index.php.

- 19. The Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs warns against all travel to Hubei province [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.krisinformation.se/en/news/2020/february/the-swedish-ministry-for-foreign-affairs-now-warns-against-all-travel-to-hubei.

- 20. Shim E, Tariq A, Choi W, et al. Transmission potential and severity of COVID-19 in South Korea. Int J Infect Dis 2020;93:339−44. PMID: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.031. PMID: 32198088. PMID: 7118661.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Contact Transmission of COVID-19 in South Korea: Novel Investigation Techniques for Tracing Contacts. Osong Public Health Res Perspect 2020;11(1). 60−3. PMID: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.1.09. PMID: 32149043. PMID: 7045882.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 22. Normile D. [Internet]. Coronavirus cases have dropped sharply in South Korea. What’s the secret to its success? Science 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 4]. Available from: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/03/coronavirus-cases-have-dropped-sharply-south-korea-whats-secret-its-success.Article

- 23. South Korea virus “emergency” as cases increase [Internet]. BBC News 2020 Feb 21 [cited 2020 Apr 8]. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-51582186.

- 24. Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare [Internet]. Coronavirus COVID-19 - Latest Updates 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 18]. Available from: https://thl.fi/en/web/infectious-diseases-and-vaccinations/what-s-new/coronavirus-covid-19-latest-updates.

- 25. Finnish Government [Internet]. Government press releases [cited 2020 Jul 18]. Available from: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/information-on-coronavirus/government-press-releases.

- 26. Ministry of Social Affairs and Health [Internet]. Preparedness for the novel coronavirus disease 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 18]. Available from: https://stm.fi/en/coronavirus-preparedness.

- 27. Nowroozpoor A, Choo EK, Faust JS. Why the United States failed to contain COVID-19. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2020;[Epub ahead of print]. Epub 2020 Jun 30. PMID: 10.1002/emp2.12155.Article

- 28. Margolin J, Meek JG. [Internet]. Intelligence report warned of coronavirus crisis as early as November: Sources. ABC News 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 10]. Available from: https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/intelligence-report-warned-coronavirus-crisis-early-november-sources/story?id=70031273.

- 29. Sachs J. [Internet]. Covid-19: Why America has the world’s most confirmed cases CNN; 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 10]. Available from: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/26/opinions/us-most-confirmed-cases-sachs/index.html.

- 30. Devlin H. [Internet]. Health experts criticise UK’s failure to track recovered Covid-19 cases. The Guardian 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/18/health-experts-criticise-uk-failure-track-recovered-covid-19-cases.

- 31. Covid-19 Coronavirus Pandemic [Internet]. Worldometer 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries.

- 32. Lowrie M. [Internet]. Canada’s long-term care system failed elders, before and during COVID-19: report. CTV News 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/canada-s-long-term-care-system-failed-elders-before-and-during-covid-19-report-1.5009940.

- 33. Basky G. All hands on deck as cases of COVID-19 surge. CMAJ 2020;192(15). E415−6. PMID: 10.1503/cmaj.1095859. PMID: 32392507. PMID: 7162446.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 34. Bronskill J. [Internet]. Coronavirus a ‘failure of early warning’ for Canada, intelligence expert says 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-coronavirus-a-failure-of-early-warning-for-canada-intelligence/.

- 35. Hartigan R. [Internet]. A look inside Thailand, which prevented coronavirus from gaining a foothold National Geographic; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/06/look-inside-thailand-prevented-coronavirus-gaining-foothold/.

- 36. Winberg M. [Internet]. Därför kan Sverige inte utfärda utegångsförbud. SVT Nyheter 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 17]. Available from: https://www.svt.se/nyheter/vetenskap/darfor-kan-sverige-inte-utfarda-utegangsforbud.

- 37. Issac A, Stephen S, Jacob J, et al. The Pandemic league of COVID-19: South Korea Vs United States, the preached lessons for entire world. J Prev Med Pub Health 2020;53(4). 228−32. PMID: 10.3961/jpmph.20.166.ArticlePDF

- 38. Lotfi M, Hamblin MR, Rezaei N. COVID-19: Transmission, prevention, and potential therapeutic opportunities. Clin Chim Acta 2020;508:254−66. PMID: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.05.044. PMID: 32474009. PMID: 7256510.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 39. Zhang N, Li C, Hu Y, et al. Current development of COVID-19 diagnostics, vaccines and therapeutics. Microbes Infect 2020;22(6–7). 231−5. PMID: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.05.001. PMID: 32387332. PMID: 7200352.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 40. Amanat F, Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines: Status Report. Immunity 2020;52(4). 583−9. PMID: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.03.007. PMID: 32259480. PMID: 7136867.ArticlePubMedPMC

References

| GHS rank | Country | Population (million) | Index case reported (MM/DD/YY) | Case/million | Deaths/ million | CFR† (%) | Recovered | RR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 331.13 | 01/20/20 | 13,388 | 450 | 3.6 | 2,036,752 | 47.57 |

| 2 | United Kingdom | 67.91 | 01/31/20 | 4,419 | 674 | 15.4 | NA | NA |

| 3 | Netherlands‡ | 17.3 | 02/27/20 | 3,101 | 358.28 | 11.8 | - | - |

| 4 | Australia | 25.52 | 01/25/20 | 600 | 6 | 1 | 9,017 | 64.65 |

| 5 | Canada | 37.76 | 01/27/20 | 3,034 | 235 | 7.9 | 99,098 | 66.41 |

| 6 | Thailand | 69.81 | 01/08/20 | 47 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 3,109 | 94.73 |

| 7 | Sweden | 10.10 | 01/31/20 | 7,858 | 564 | 7.2 | NA | NA |

| 8 | Denmark‡ | 5.9 | 02/27/20 | 2,338 | 105.49 | 4.6 | - | - |

| 9 | South Korea | 51.27 | 01/20/20 | 277 | 6 | 2.1 | 12,866 | 91.30 |

| 10 | Finland | 5.54 | 01/29/20 | 1,335 | 59 | 4.5 | 6,920 | 93.67 |

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Are population movement restrictions containing the COVID-19 cases in Sub-Saharan Africa?

Maria Sassi, Gopal Trital

Development Southern Africa.2023; 40(4): 881. CrossRef - Communication to promote and support physical distancing for COVID-19 prevention and control

Rebecca E Ryan, Charlotte Silke, Anne Parkhill, Ariane Virgona, Bronwen Merner, Shauna Hurley, Louisa Walsh, Caroline de Moel-Mandel, Lina Schonfeld, Adrian GK Edwards, Jessica Kaufman, Alison Cooper, Rachel Kar Yee Chung, Karla Solo, Margaret Hellard, Gi

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - Paediatric orthopaedic surgery during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. A safe and pragmatic approach to service provision

Ibrar Majid, Tahani Fowzi Al Ali, M.A. Serour, Hisham M. Elsayed, Yousra Samir, Ajay Prashanth Dsouza, Hayder Saleh AlSaadi, Sattar Alshryda

The Surgeon.2022; 20(6): e338. CrossRef - An evidence-based nursing care guide for critically ill patients with COVID-19: A scoping Review

Manju Dhandapani, Vijay VR, Nadiya Krishnan, Lakshmanan Gopichandran, Alwin Issac, Shine Stephen, Jaison Jacob, Thilaka Thilaka, Lakshmi Narayana Yaddanapudi, Sivashanmugam Dhandapani

Asian Journal of Nursing Education and Research.2022; : 144. CrossRef - An examination of Thailand’s health care system and strategies during the management of the COVID-19 pandemic

Alwin Issac, Rakesh Vadakkethil Radhakrishnan, VR Vijay, Shine Stephen, Nadiya Krishnan, Jaison Jacob, Sam Jose, SM Azhar, Anoop S Nair

Journal of Global Health.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Somatoform Symptoms among Frontline Health-Care Providers during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Jaison Jacob, VR Vijay, Alwin Issac, Shine Stephen, Manju Dhandapani, Nadiya Krishnan, VR Rakesh, Sam Jose, Anoop S. Nair, SM Azhar

Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine.2021; 43(3): 272. CrossRef - How the nations should gear up for future pandemics?

Alwin Issac, VR Vijay, Nadiya Krishnan, Jaison Jacob, Shine Stephen, Rakesh Vadakkethil Radhakrishnan, Manju Dhandapani

Journal of Global Health.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Determinants of Willingness for COVID-19 Vaccine: Implications for Enhancing the Proportion of Vaccination Among Indians

Jaison Jacob, Shine Stephen, Alwin Issac, Nadiya Krishnan, Rakesh Vadakkethil Radhakrishnan, Vijay V R, Manju Dhandapani, Sam Jose, Azhar SM, Anoop S Nair

Cureus.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - O Papel da Telessaúde na Pandemia Covid-19: Uma Experiência Brasileira

Rodolfo Souza da Silva, Carlos André Aita Schmtiz, Erno Harzheim, Cynthia Goulart Molina-Bastos, Elise Botteselle de Oliveira, Rudi Roman, Roberto Nunes Umpierre, Marcelo Rodrigues Gonçalves

Ciência & Saúde Coletiva.2021; 26(6): 2149. CrossRef - Scrutiny of COVID-19 response strategies among severely affected European nations

Shine Stephen, Alwin Issac, Rakesh Vadakkethil Radhakrishnan, Jaison Jacob, VR Vijay, Sam Jose, SM Azhar, Anoop S. Nair, Nadiya Krishnan, Rakesh Sharma, Manju Dhandapani

Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives.2021; 12(4): 203. CrossRef

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite