Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Osong Public Health Res Perspect > Volume 14(5); 2023 > Article

-

Short Communication

Perceptions of older adults and generativity among older citizens in Japan: a descriptive cross-sectional study -

Yuho Shimizu1,2,3

, Tomoya Takahashi1

, Tomoya Takahashi1 , Kenichiro Sato1

, Kenichiro Sato1 , Susumu Ogawa1

, Susumu Ogawa1 , Daisuke Cho1

, Daisuke Cho1 , Yoshifumi Takahashi1

, Yoshifumi Takahashi1 , Daichi Yamashiro1

, Daichi Yamashiro1 , Yan Li1

, Yan Li1 , Keigo Hinakura1

, Keigo Hinakura1 , Ai Iizuka1

, Ai Iizuka1 , Tomoki Furuya1

, Tomoki Furuya1 , Hiroyuki Suzuki1

, Hiroyuki Suzuki1

-

Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives 2023;14(5):427-432.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24171/j.phrp.2023.0063

Published online: October 10, 2023

1Research Team for Social Participation and Healthy Aging, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Tokyo, Japan

2Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

3Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, Japan

- Correspondence to: Yuho Shimizu Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan E-mail: yuhos1120mizu@gmail.com

© 2023 Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

- 1,260 Views

- 56 Download

Abstract

-

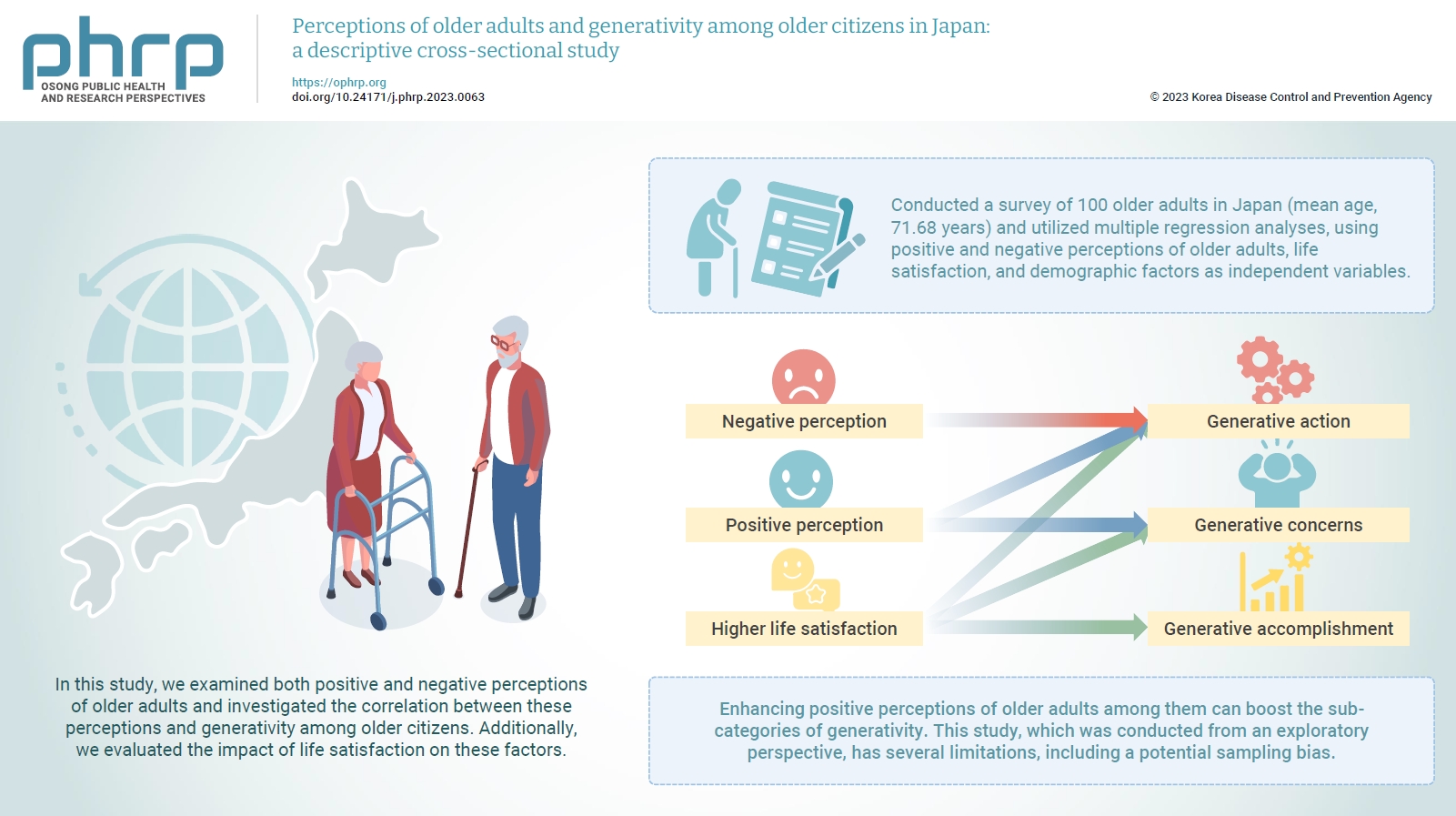

Objectives

- As the population ages worldwide, including in Japan, there is a growing expectation for older adults to remain active participants in society. The act of sharing one’s experiences and knowledge with younger generations through social engagement not only enriches the lives of older individuals, but also holds significant value for our society. In this study, we examined both positive and negative perceptions of older adults and investigated the correlation between these perceptions and generativity among older citizens. Additionally, we evaluated the impact of life satisfaction on these factors.

-

Methods

- We conducted a survey of 100 older adults in Japan (mean age, 71.68 years) and utilized multiple regression analyses, using positive and negative perceptions of older adults, life satisfaction, and demographic factors as independent variables. The sub-categories of generativity—namely, generative action, concern, and accomplishment—were used as dependent variables.

-

Results

- Participants who held a more positive perception of older adults demonstrated a higher level of generative actions and concerns. Additionally, participants who reported higher levels of life satisfaction also exhibited more generative actions, concerns, and accomplishments. Conversely, those who held a more negative perception of older adults were found to have higher levels of generative actions.

-

Conclusion

- Enhancing positive perceptions of older adults among them can boost the sub-categories of generativity. This study, which was conducted from an exploratory perspective, has several limitations, including a potential sampling bias. A more comprehensive examination of the relationship between perceptions of older adults and generativity is anticipated in future research.

- Population aging is progressing worldwide, including in Japan, where individuals aged 65 and above comprise 29.1% of the total population [1]. The falling birthrate and aging population are anticipated to pose significant societal challenges. In light of these circumstances, it is crucial for older adults to actively participate in society to invigorate local communities and bolster the labor force [2]. The act of sharing one’s experiences and knowledge with the younger generation through social participation not only enriches the lives of older citizens, but is also meaningful for our society.

- In this study, we explored the concept of generativity, which pertains to the transmission of experiences and knowledge from older to younger generations. Erikson [3] defined generativity as the interest in nurturing and guiding the next generation, primarily through the act of parenting [4]. However, recent trends such as increased life expectancy and delayed marriages have led to a broader interpretation of generativity as a psychological and social issue encompassing adulthood and old age [5]. Indeed, research involving older adults has demonstrated that those with higher levels of generativity tend to experience greater life satisfaction [6,7] and are more likely to participate in local parenting support initiatives [4]. Generativity comprises the following elements: (1) generative action, which includes specific actions like sharing personal experiences; (2) generative concern, which signifies an interest in engaging with younger generations and in creative activities; and (3) generative accomplishment, which conveys a sense of societal contribution and involvement in passing experiences to younger generations [4]. By differentiating these components and identifying the psychological variables linked to them, we can effectively develop psychological interventions to enhance generativity among older individuals.

- We also examined positive and negative perceptions of older adults. As the elderly population expands, the range of individual perceptions about older people is likely to broaden. In terms of the relationship between these perceptions and generativity, older adults who hold more positive views of themselves are often proud of their peer group (i.e., older adults), and are inclined to share their experiences and knowledge with younger generations. This is likely because older adults who maintain positive old-age stereotypes tend to have better mental health [8–10] and are more likely to engage actively in generative actions. On the other hand, those who hold negative views of older adults may be more reluctant to share their experiences with younger generations.

- The literature presents common stereotypes about old age as both negative, including descriptors like “slow” and “feeble,” and positive, with terms such as “warm” and “gentle” [11,12]. These ambivalent stereotypes suggest that the positive and negative perceptions of the elderly are not mutually exclusive. In other words, a certain segment of the older population may view their social group in both a positive and negative light. With this in mind, we separately assessed the positive and negative perceptions of the elderly and explored the relationship between these perceptions and generativity.

- A variable that must be accounted for when investigating this relationship is life satisfaction. Individuals with greater life satisfaction tend to have higher self-esteem [13,14] and fewer depressive tendencies [15,16], making them more likely to perceive the ingroup (i.e., older adults) in a positive light. Furthermore, there is a positive correlation between generativity and life satisfaction among older adults [6,7,17]. Consequently, we aimed to explore the relationship between positive and negative perceptions of older adults and generativity, after controlling for life satisfaction.

Introduction

- Participants

- We performed a power analysis assuming a medium to large effect size (f2=0.20, Nparameter=7, α=0.05, βpower=0.80), and the required sample size was N=80. A total of 100 older Japanese, comprising 10 men and 90 women in urban areas, participated in this study (mean, 71.68 years; range, 65–86 years). They were enrolled in a health program implemented by a Japanese municipality in 2021 to train volunteers to read picture books to children. The ethics committee of the authors’ institution approved this study.

- Measurements

- We utilized the 16-item measure developed by Toyoshima et al. [18] to evaluate both positive and negative perceptions of the elderly, with 8 items dedicated to each. Positive perceptions were gauged using descriptors such as “cheerful” and “active,” while negative perceptions were measured with terms like “sickly” and “dependent.” Participants were shown these descriptors and asked to rate the extent to which they believed each term applied to older adults. Their responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1, representing strong disagreement, to 5, representing strong agreement. The mean was used as the score (α=0.76, 0.87, respectively), with higher scores indicating a more pronounced perception. While the correlations between this scale and existing ageism scales remain unknown, the items used in this study are believed to accurately represent stereotypes of old age in Japan [18,19].

- We measured generativity using the revised Japanese version of the Generativity Scale [4], comprising 4 items related to generative action, 4 items related to generative concern, and 4 items related to generative accomplishment. Participants were asked to rate their responses on a 6-point Likert scale, with 0, indicating strong disagreement, to 5, indicating strong agreement. We calculated the mean score for each sub-category (α=0.94, 0.85, and 0.87, respectively), with higher scores signifying greater generativity. A factor analysis revealed that the same factors identified in Murayama et al. [4] were extracted (refer to Open Science Framework [OSF], https://osf.io/unyh5/).

- Life satisfaction was measured using the satisfaction with life scale [20]. This involved participant rating 5 items, one of which was “I am satisfied with my life,” on a 7-point Likert scale. The scale ranged from 1, representing strong disagreement, to 7, indicating strong agreement. The average score was used (α=0.83), with higher scores signifying greater life satisfaction. In terms of demographic variables, participants were queried about their educational background in terms of years, their age, and their gender.

- Procedure and Analysis

- Participants were briefed about the study and gave their consent to participate. They then responded to questions concerning their perceptions of older adults, generativity, life satisfaction, and demographic information. The statistical software R ver. 4.1.0 (The R Foundation) was utilized for the analysis. Multiple regression analyses were performed using the perceptions of older adults, life satisfaction, and demographic variables as independent variables, and the sub-categories of generativity (generative action, concern, and accomplishment) as dependent variables. The questionnaire items, data used in the analysis, R codes, and histograms for each indicator can be accessed on the OSF.

Materials and Methods

- Summary statistics for each indicator are presented in Table 1. Participants who held more positive perceptions of older adults demonstrated more generative actions, concerns, and accomplishments, respectively (r=0.27, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08–0.44, p=0.006; r=0.24, 95% CI, 0.05–0.42, p=0.01; r=0.21, 95% CI, 0.02–0.39, p=0.04). Additionally, participants who reported higher life satisfaction also showed more generative actions, concerns, and accomplishments, respectively (r=0.38, 95% CI, 0.20–0.54, p<0.001; r=0.32, 95% CI, 0.13–0.49, p=0.001; r=0.46, 95% CI, 0.29–0.60, p<0.001). The correlation coefficients between the variables for groups with higher and lower average years of education (M=14.03) were included in the OSF. Consequently, correlations similar to those in the main analysis were found in both groups.

- Multiple regression analyses were performed using positive and negative perceptions of the elderly, life satisfaction, and demographic variables as independent variables, with the sub-categories of generativity serving as dependent variables (Table 2). The results indicated that participants who held more positive perceptions of older adults demonstrated more generative actions and concerns (β=0.25, 95% CI, 0.06–0.44, p=0.01; β=0.21, 95% CI, 0.004–0.41, p=0.046). Conversely, participants with more negative perceptions of older adults showed more generative actions (β=0.22, 95% CI, 0.02–0.43, p=0.03). Participants who reported higher levels of life satisfaction exhibited more generative actions, concerns, and accomplishments (β=0.38, 95% CI, 0.19–0.58, p<0.001; β=0.31, 95% CI, 0.11–0.51, p=0.003; β=0.43, 95% CI, 0.23–0.62, p<0.001). A post-hoc power analysis was performed using the adjusted coefficient of determination (adjusted R2) in multiple regression analyses (Nsample=100, Nparameter=7, α=0.05), which yielded the following results βpower=0.95 (generative action), βpower=0.75 (generative concern), and βpower=0.95 (generative accomplishment). While these are considered to be acceptable levels, the limitation caused by the small R2 is discussed below.

Results

- In this study, we surveyed older Japanese adults to explore the relationship between positive and negative perceptions of older adults and generativity, encompassing generative action, concern, and accomplishment [4]. The results suggested that, even when accounting for life satisfaction and demographic factors, participants who held more positive views of older adults were more likely to exhibit increased generative actions and concerns. Conversely, those with more negative perceptions of older adults demonstrated a higher level of generative actions.

- Participants with more positive perceptions of older adults tended to exhibit better mental health [8−10] and a strong sense of pride in their association with the older adult social group, as well as in their personal accomplishments. These individuals are often more inclined to share their experiences and knowledge with younger generations and are more likely to take proactive steps to do so. Interestingly, while only life satisfaction influenced generative accomplishment, both life satisfaction and positive perceptions of older adults showed a positive correlation (r=0.24) (Table 1). These results suggest that enhancing positive perceptions of older adults among them could potentially boost the sub-categories of generativity.

- Meanwhile, participants with more negative perceptions of older adults demonstrated higher levels of generative behavior. This may be because those with negative views of older adults are more likely to use their own past and current behaviors as cautionary tales for younger generations. However, the correlation between negative perceptions of older adults and generativity was small (Table 1), so this finding should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, given the moderate negative correlation between positive and negative perceptions of older adults (r=–0.35) [21], it may be possible to enhance positive perceptions of older adults without necessarily reducing negative ones. Among the ambivalent stereotypes of old age [11,12], focusing on increasing positive perceptions of older adults, rather than reducing negative ones, could be an effective strategy for boosting generativity among older adults.

- Despite the above findings, our study has 4 major limitations. First, 90% of our participants were female. While we accounted for gender in our analysis, it remains uncertain whether the same results would be observed in an older male population. Previous studies have indicated that generativity tends to be higher among older males than older females [4,22], suggesting that the relationship between perceptions of older adults and generativity may differ by gender. It is worth noting that when we conducted the analysis using only data from women, the results were consistent with those in the main analysis (see OSF). Second, all participants in this study were Japanese. Therefore, the impact of cultural differences on the relationship between perceptions of older adults and generativity warrants further investigation in future research. Third, our participant pool was limited to those enrolled in a health program that trains volunteers to read picture books to children. Consequently, their health status and levels of generativity might be higher than those of the general older population. However, the average scores for the sub-categories of generativity in this study were not excessively high compared to the values in Murayama et al. [4], where participants were randomly selected older individuals aged 65 to 84 years from an urban area in Japan. Thus, it would be unjust to claim that our participants significantly deviate from the general older population. Finally, the coefficients of determination in our multiple regression analyses were relatively small. Prior research has identified agentic and communal goal attainment [23] and psychological well-being [17,24] as being strongly associated with generativity. Therefore, it is necessary to reevaluate our findings after controlling for these variables.

Discussion

- The findings of this study indicate that enhancing the positive perceptions of the ingroup (i.e., older adults) could potentially boost generativity. Concurrently, it has been documented that sharing their experiences and wisdom with younger generations can contribute to the preservation of older adults’ physical and mental health. We anticipate a virtuous cycle where healthier older adults foster more positive perceptions of themselves, thereby increasing generativity. While a comprehensive interpretation of our data is challenging, it would be beneficial to further explore the interconnections among perceptions of older adults, generativity, and health status in older citizens. The heightened generativity in older adults could also promote intergenerational interaction, enabling younger generations to learn from the life experiences of their elders. We are eager to undertake empirical studies that concentrate on the generativity of older adults.

Conclusion

- • Passing on older adults’ experiences to the younger generation is meaningful for our society.

- • We conducted a survey of 100 older adults in Japan.

- • Participants with more positive perceptions of older adults had more generativity.

- • Participants with higher levels of life satisfaction had more generativity.

- • A more detailed survey of the link between perceptions of older adults and generativity is expected.

HIGHLIGHTS

-

Ethics Approval

The ethics committee of Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Geriatrics and Gerontology approved this study and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

-

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (22H01098).

-

Availability of Data

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository (https://osf.io/unyh5/).

-

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: YS, TT; Data curation: all authors; Formal analysis: YS; Funding acquisition: HS; Investigation: YS, TT; Methodology: YS; Project administration: HS; Supervision: HS; Writing–original draft: YS; Writing–review & editing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Additional Contributions

The authors acknowledge the continued efforts in the management of survey by Senior Citizen Activities Promotion Section in Welfare Division of Hachioji City in Tokyo, Japan. The authors also thank members of the research team for social participation and healthy aging in Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Geriatrics and Gerontology.

Article information

| No. | Mean±SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.39±0.98 | ||||||||

| 2 | 3.41±0.83 | 0.55** | |||||||

| 3 | 1.99±1.05 | 0.64** | 0.46** | ||||||

| 4 | 3.24±0.44 | 0.27** | 0.24* | 0.21* | |||||

| 5 | 3.12±0.55 | –0.01 | –0.05 | –0.16 | –0.35** | ||||

| 6 | 4.32±1.00 | 0.38** | 0.32** | 0.46** | 0.24* | –0.35** | |||

| 7 | 14.03±2.53 | 0.07 | 0.14 | –0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | ||

| 8 | 71.68±5.15 | –0.06 | 0.02 | –0.14 | 0.06 | –0.12 | –0.07 | –0.15 | |

| β (95% CI) | VIF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action | Concern | Accomplishment | ||

| Positive perception | 0.25 (0.06 to 0.44)* | 0.21 (0.004 to 0.41)* | 0.13 (–0.07 to 0.32) | 1.16 |

| Negative perception | 0.22 (0.02 to 0.43)* | 0.14 (–0.07 to 0.35) | 0.03 (–0.17 to 0.23) | 1.28 |

| Life satisfaction | 0.38 (0.19 to 0.58)** | 0.31 (0.11 to 0.51)** | 0.43 (0.23 to 0.62)** | 1.19 |

| Years of education | 0.03 (–0.15 to 0.22) | 0.13 (–0.06 to 0.32) | –0.06 (–0.24 to 0.12) | 1.03 |

| Age | –0.02 (–0.21 to 0.16) | 0.06 (–0.13 to 0.26) | –0.13 (–0.31 to 0.06) | 1.05 |

| Sex (0=male, 1=female) | –0.15 (–0.33 to 0.03) | –0.11 (–0.30 to 0.08) | –0.07 (–0.25 to 0.12) | 1.02 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.19 (0.07 to 0.32)** | 0.12 (0.01 to 0.23)** | 0.19 (0.07 to 0.32)** | |

- 1. Statistics Bureau of Japan. Statistics on the elderly in Japan [Internet]. Statistics Bureau of Japan; 2022 [cited 2023 Mar 2]. Available from: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/topics/topi1320.html Japan.

- 2. Townsend BG, Chen JT, Wuthrich VM. Barriers and facilitators to social participation in older adults: a systematic literature review. Clin Gerontol 2021;44:359−80.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Erikson EH. Childhood and society. Norton and Company; 1950.

- 4. Murayama S, Kobayashi E, Kuraoka M, et al. Development of revised Japanese version of Generativity Scale (JGS-R) and investigation of its reliability and validity. Jpn J Pers 2022;30:151−60. Japan.Article

- 5. Cheng ST. Generativity in later life: perceived respect from younger generations as a determinant of goal disengagement and psychological well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64:45−54.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Adams-Price CE, Nadorff DK, Morse LW, et al. The creative benefits scale: connecting generativity to life satisfaction. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2018;86:242−65.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 7. An JS, Cooney TM. Psychological well-being in mid to late life: the role of generativity development and parent-child relationships across the lifespan. Int J Behav Dev 2006;30:410−21.ArticlePDF

- 8. Levy B. Stereotype embodiment: a psychosocial approach to aging. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2009;18:332−6.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 9. Levy BR, Hausdorff JM, Hencke R, et al. Reducing cardiovascular stress with positive self-stereotypes of aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2000;55:P205−13.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Levy BR, Slade MD, May J, et al. Physical recovery after acute myocardial infarction: positive age self-stereotypes as a resource. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2006;62:285−301.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 11. Cadieux J, Chasteen AL, Packer DJ. Intergenerational contact predicts attitudes toward older adults through inclusion of the outgroup in the self. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2019;74:575−84.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Fernandez-Ballesteros R, Olmos R, Perez-Ortiz L, et al. Cultural aging stereotypes in European countries: are they a risk to active aging? PLoS One 2020;15:e0232340.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Kang SM, Shaver PR, Sue S, et al. Culture-specific patterns in the prediction of life satisfaction: roles of emotion, relationship quality, and self-esteem. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2003;29:1596−608.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 14. Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, et al. The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J Couns Psychol 2006;53:80−93.Article

- 15. Chang EC, Sanna LJ. Optimism, pessimism, and positive and negative affectivity in middle-aged adults: a test of a cognitive-affective model of psychological adjustment. Psychol Aging 2001;16:524−31.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Tremblay M, Blanchard CM, Pelletier LG, et al. A dual route in explaining health outcomes in natural disaster. J Appl Soc Psychol 2006;36:1502−22.

- 17. McAdams DP, St Aubin ED, Logan RL. Generativity among young, midlife, and older adults. Psychol Aging 1993;8:221−30.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Toyoshima A, Tabuchi M, Sato S. Relationship between recognition of elder abuse and attitude toward elderly people among young adults. Jpn J Gerontol 2016;38:308−18.

- 19. Suda A, Masumoto T. Changes of nursing students’ images of the elderly caused by lectures, exercise and practice. Bull Kawasaki College Allied Health Prof 2006;26:29−36.

- 20. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, et al. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 1985;49:71−5.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155−9.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Schoklitsch A, Baumann U. Measuring generativity in older adults: the development of new scales. GeroPsych 2011;24:31−43.Article

- 23. Au A, Lai S, Wu W, et al. Generativity and positive emotion in older adults: mediation of achievement and altruism goal attainment across three cultures. J Happiness Stud 2020;21:677−92.ArticlePDF

- 24. Hirose J, Kotani K. How does inquisitiveness matter for generativity and happiness? PLoS One 2022;17:e0264222.ArticlePubMedPMC

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Cite

Cite