Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Osong Public Health Res Perspect > Volume 14(6); 2023 > Article

-

Original Article

Factors affecting depression and health-related quality of life in the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic -

Deok-Ju Kim

-

Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives 2023;14(6):520-529.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24171/j.phrp.2023.0166

Published online: November 16, 2023

Department of Occupational Therapy, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Cheongju University, Cheongju, Republic of Korea

- Corresponding author: Deok-Ju Kim Department of Occupational Therapy, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Cheongju University, 298 Daeseong-ro, Cheongwon-gu, Cheongju 28503, Republic of Korea E-mail: dj7407@hanmail.net

© 2023 Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

- 859 Views

- 42 Download

Abstract

-

Objectives

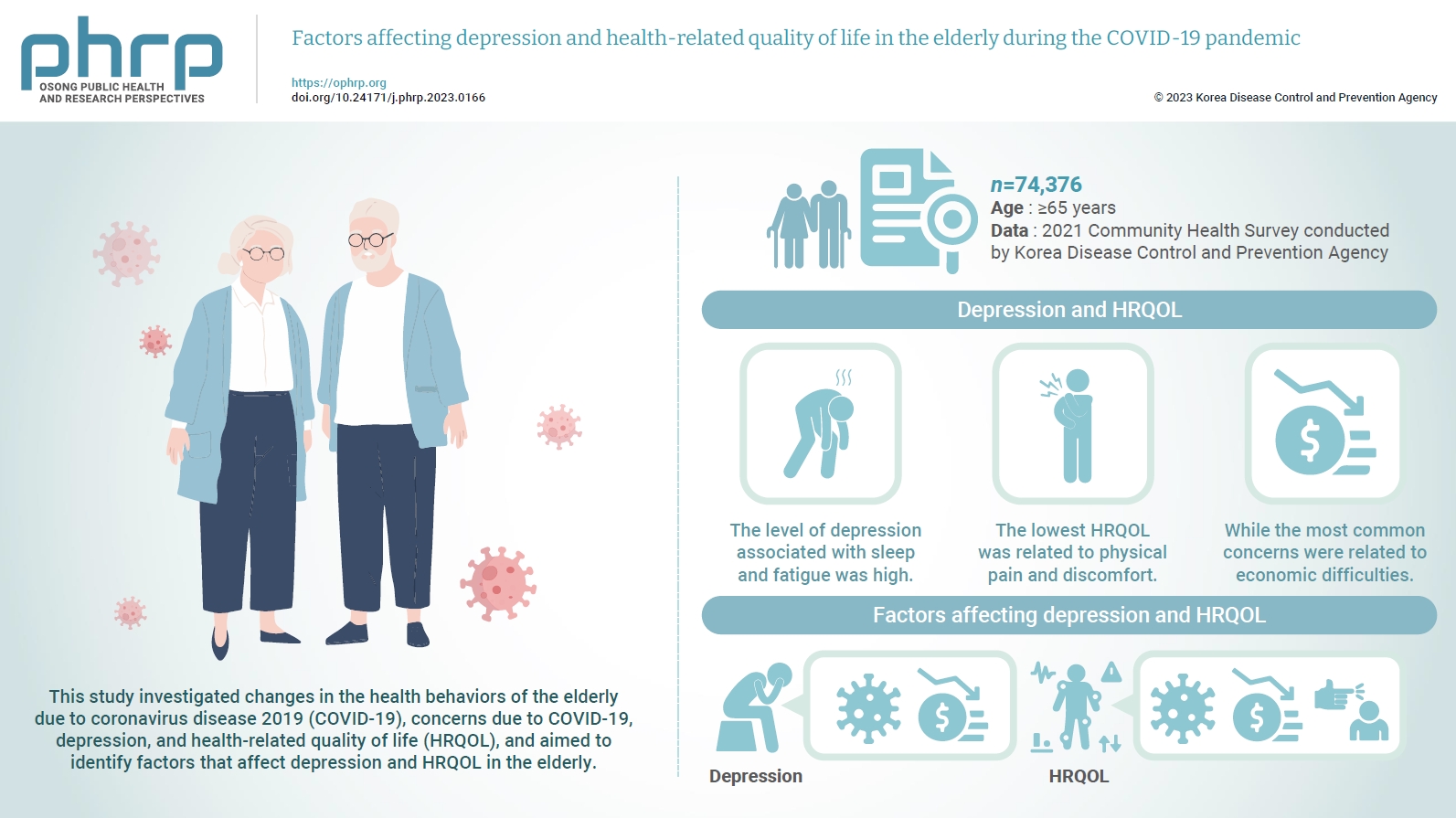

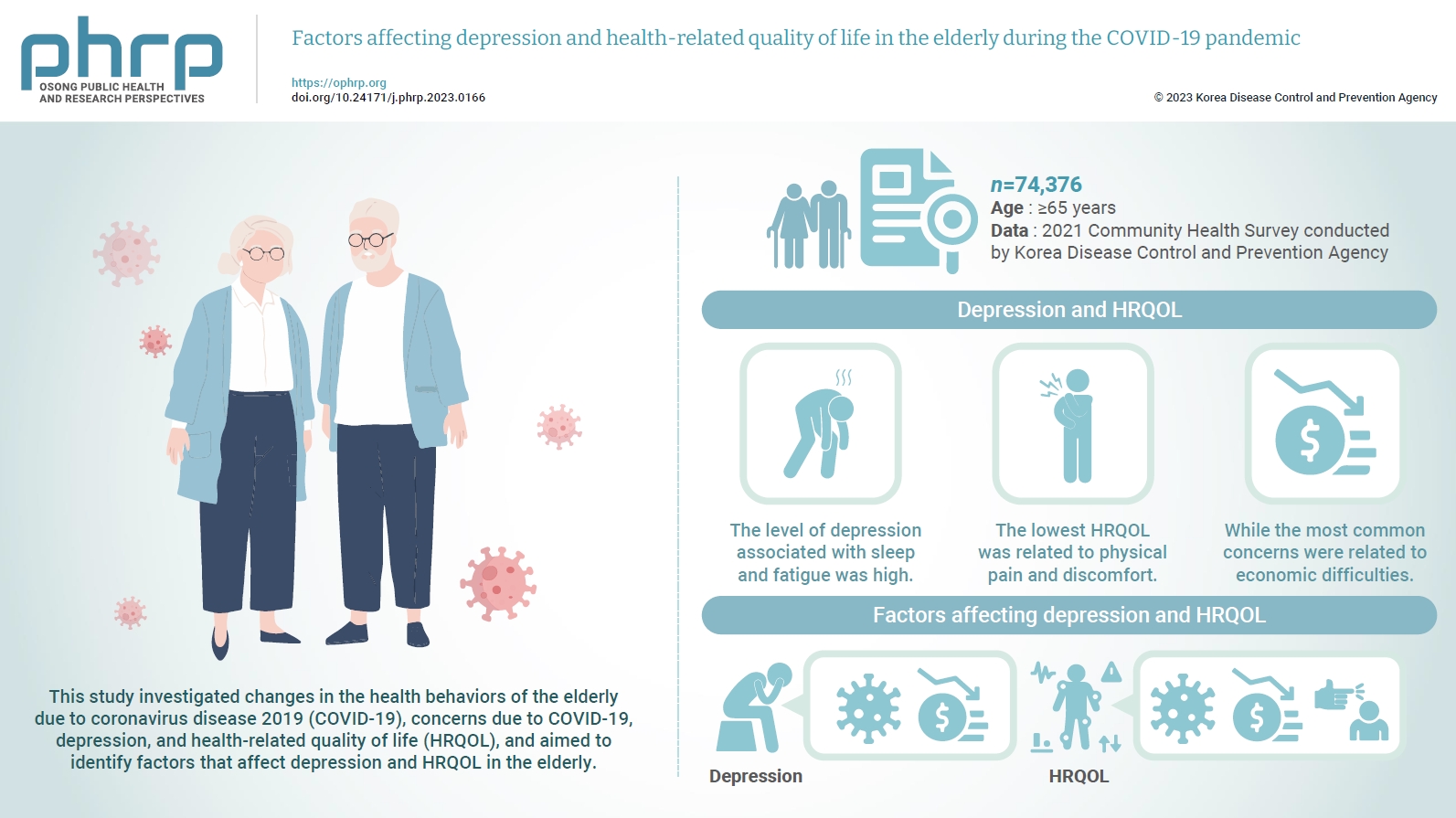

- This study investigated changes in the health behaviors of the elderly due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), concerns due to COVID-19, depression, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and aimed to identify factors that affect depression and HRQOL in the elderly.

-

Methods

- This study was conducted using data from the 2021 Community Health Survey of the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. From a total sample size of 229,242 individuals, 74,376 elderly people aged 65 or older were selected as subjects, and changes in health behaviors, concerns due to COVID-19, depression, and HRQOL were measured and analyzed.

-

Results

- The level of depression associated with sleep and fatigue was high. The lowest HRQOL was related to physical pain and discomfort, while the most common concerns were related to economic difficulties. Factors influencing depression included worries about infection and economic harm, while factors impacting HRQOL encompassed concerns about infection, economic harm, and criticism from others.

-

Conclusion

- If an infectious disease situation such as COVID-19 reoccurs in the future, it will be necessary to encourage participation in hybrid online and offline programs at senior welfare centers. This should also extend to community counseling institutions like mental health welfare centers. Additionally, establishing connections with stable senior job projects can help to mitigate the effects of social interaction restrictions, physical and psychological health issues, and economic difficulties experienced by the elderly.

- The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) spread rapidly worldwide, leading the World Health Organization to declare a pandemic in March 2020 [1]. This disease has significantly impacted various aspects of our lives, including the economy, society, and culture. One of the most notable changes following the outbreak of COVID-19 has been the transformation of our social networks [2]. COVID-19 is primarily transmitted through interpersonal contact and droplets, making limiting face-to-face interactions a key strategy in reducing its spread. Consequently, governments have developed and implemented various social distancing measures [3]. While social distancing is effective in preventing the spread of COVID-19, it also carries the risk of social isolation. Many individuals have faced significant restrictions in their relationships with family and friends, as well as in their social interactions, due to sudden isolation from their external environment and limitations on their daily activities. This is particularly true for the elderly, who often struggle with adapting to environmental changes and may find non-face-to-face communication methods, such as social networking services, challenging. This has often resulted in a more isolated lifestyle, leading to an increase in depression [4]. Furthermore, the spread of inaccurate information through various media outlets has fueled anxiety and fear about the spread of infectious diseases. As concerns about infection rise, it is anticipated that this will negatively impact not only the mental health of the elderly, but also their health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

- Depression is a common mental illness in old age, and it significantly impacts life satisfaction among the elderly [5]. The elderly population is particularly susceptible to depression due to the physical decline associated with aging, as well as social factors such as isolation and the loss of relationships [6]. For instance, during the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in Hong Kong in 2003, the elderly experienced heightened levels of loneliness and isolation due to the cessation of social and family gatherings, medical treatments, and participation in senior-related institutions. Consequently, the suicide rate among the elderly in Hong Kong surged by approximately 32% the following year [7]. This serves as a reminder of the critical importance of addressing the psychological needs of the elderly, particularly in the context of a pandemic such as COVID-19.

- In the realm of physical function, health behaviors frequently serve as indicators for assessing the level of care required and the success of aging [8]. It has been observed that elderly individuals who exhibit high performance in health behaviors are often able to maintain good cognitive function and enjoy a high HRQOL [9]. However, research has indicated that social distancing has led to decreased physical activity and altered exercise behaviors among the elderly, which in turn has negatively impacted their overall performance in activities of daily living [4,10].

- Research is currently being conducted on the issues faced by the elderly due to COVID-19, with a primary focus on the epidemiological characteristics and current status of this demographic. However, there is a noticeable lack of comprehensive research that also considers psychological problems and aspects of HRQOL. COVID-19 has been reclassified from a first-degree infectious disease to a second-degree infectious disease, and most social distancing measures have been lifted. Nevertheless, given the uncertainty of when another infectious disease outbreak might occur, it is crucial to understand the impact of COVID-19 on the elderly and to prepare for future infectious disease scenarios. This study is a secondary analysis using data from the 2021 Community Health Survey. The aim is to understand the current changes in health behaviors among the elderly due to COVID-19, their concerns related to the disease, depression, and HRQOL. Ultimately, the goal is to identify factors that influence depression and HRQOL in the elderly population.

Introduction

- Participants

- This study utilized raw data from the 2021 Community Health Survey conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. The purpose of the Community Health Survey is to generate community health statistics that can be used to establish and evaluate community health care plans, as mandated by the Community Health Act. The 2021 dataset included new items related to COVID-19, in addition to the existing data. The data collection period spanned from August 16, 2021, to October 31, 2021. The Community Health Survey is executed through the collaborative efforts of 3 committees and management offices, in conjunction with the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, various cities and provinces, public health centers, and responsible universities. The survey targeted adults aged 19 years or older who resided in the sample households. The survey was conducted as a one-on-one electronic survey, comprising 18 areas and 163 questions. Trained surveyors visited the sample households to administer the survey [11]. The Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency appointed a third-party agency to verify the survey data and ensure quality control. This agency re-extracted 13% of the completed surveys and conducted a telephone inspection. The survey was administered to 229,242 adults aged 19 years or older. Of these, 74,492 were aged 65 years or older. After excluding 116 patients with missing values in general characteristics, health behavior, and items of concern, 74,376 patients were included in the final analysis.

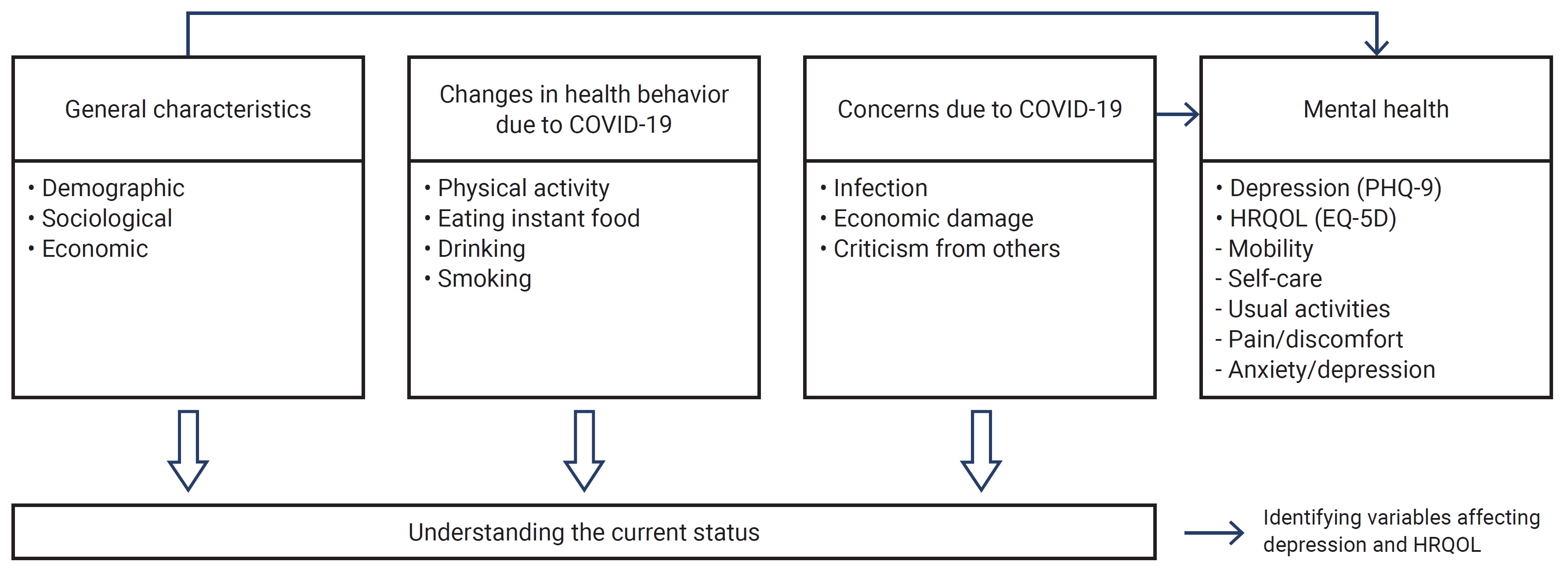

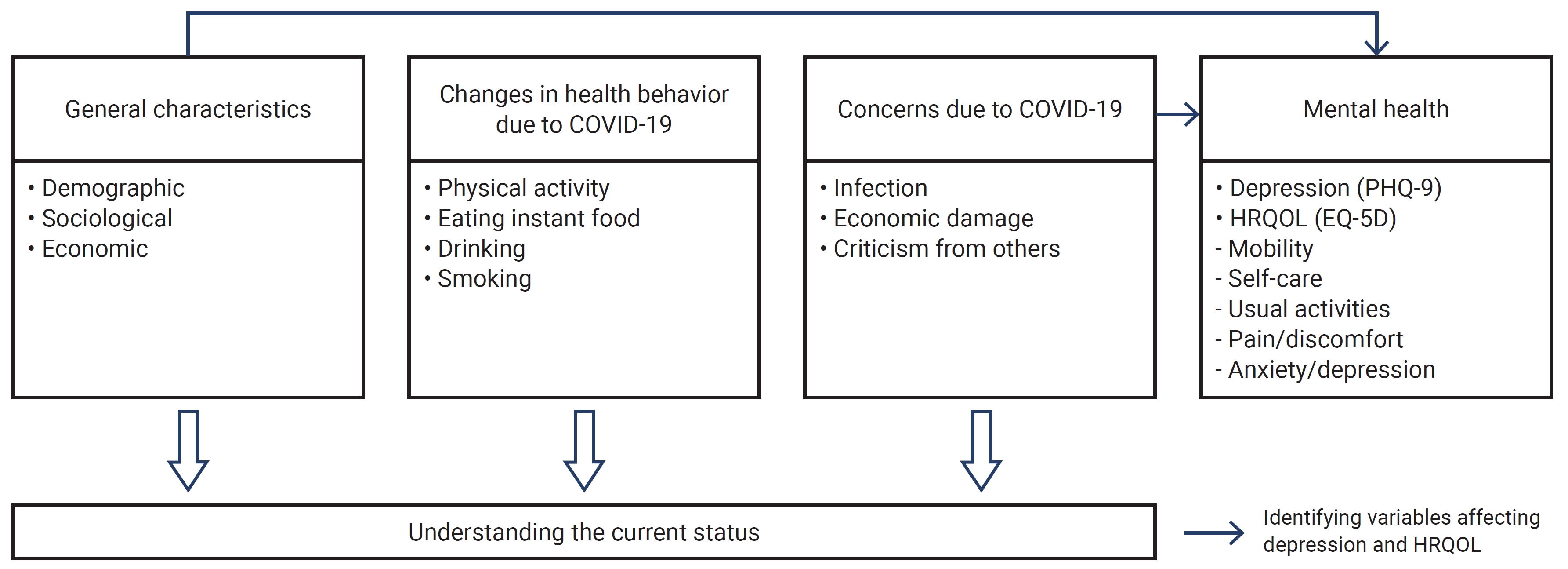

- Research Model

- This study explored the demographic, sociological, and economic traits of the elderly population, as well as the current shifts in health behavior and concerns brought about by COVID-19. It also aimed to identify the factors influencing depression and HRQOL. The research model is depicted in Figure 1.

- Measurements

- Four items were utilized to inquire about changes in health behaviors due to COVID-19: physical activity (such as walking and exercise), consumption of instant food or soda, drinking, and smoking. For each question, participants were asked, “How has this changed compared to before COVID-19?” Responses were scored as follows: 1 point for “increased,” 2 points for “similar,” 3 points for “decreased,” and 4 points for “not applicable.”

- In relation to concerns arising from COVID-19, 3 specific items were addressed: concern about infection, concern about criticism from others due to infection, and concern about economic damage due to COVID-19. For each item, respondents were asked the question, “How concerned are you about the following due to COVID-19?” They were then instructed to rate their level of concern on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 point for “very concerned,” 2 points for “concerned,” 3 points for “somewhat concerned,” 4 points for “not very concerned,” and 5 points for “not concerned at all.” A higher score indicates a lower level of concern.

- In this study, depression was measured using the patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a depression screening tool. This self-report test is designed to gauge the severity of depression, and it comprises 9 sub-items. The scores are summed to determine the level of depression: 0-4 points indicate normal levels, 5 to 9 points suggest mild depression, 10 to 19 points denote moderate depression, and a score of 20 or more signifies severe depression. Essentially, a higher score corresponds to a higher level of depression. The test-retest reliability of the PHQ-9, as measured by Cronbach alpha, was found to be 0.89, while its concurrent validity was determined to be 0.81 [12].

- In this study, we utilized the EuroQoL-5 dimensions (EQ-5D) index to measure HRQOL. This index was specifically designed to measure HRQOL based on a variety of dimensions. The EQ-5D index comprises questions that assess the current health status in 5 key areas: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each item is scored as follows: “no problem” earns 1 point, “slight problem” earns 2 points, and “severe problem” earns 3 points. The resulting score provides a comprehensive indication of HRQOL, with a lower score signifying a higher HRQOL [13]. The test-retest reliability of this tool, as measured by Cronbach alpha, was found to be 0.93, and its convergent validity was determined to be 0.85 [14].

- Statistical Analysis

- The data collected were analyzed using the IBM SPSS ver. 27.0 (IBM Corp.). We calculated the general characteristics, changes in health behaviors due to COVID-19, and the current state of concerns related to COVID-19 using frequencies and percentages. The results for depression and HRQOL were calculated as means and standard deviations. To determine the impact of general characteristics and COVID-19-related concerns on depression and HRQOL, we used the independent t-test and analysis of variance, as well as multiple regression analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Materials and Methods

Changes in health behaviors due to COVID-19

Concerns due to COVID-19

Depression

HRQOL

- Participant Characteristics

- Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the study participants. The gender distribution was 42.3% male and 57.7% female. In terms of age, 40,288 participants (54.2%) were between 65 and 74 years old, 27,345 (36.8%) were between 75 and 84 years old, and 6,743 (9.1%) were 85 years or older. The majority of participants, 46,470 (62.5%), lived with a spouse. A significant portion, 43,904 (59.0%), were not engaged in economic activities, outnumbering those who were. Regarding changes in total income due to COVID-19, the majority, 54,334 (73.1%), reported no change. Similarly, 54,803 (73.7%) reported no change in spending on major items related to COVID-19.

- Changes in Health Behaviors due to the COVID-19

- Table 2 shows the results for changes in health behaviors due to COVID-19. For physical activities such as walking and exercise, the most common response was “similar to before COVID-19,” with 40,046 respondents (53.8%). However, the second most common response was “decreased,” reported by 24,240 respondents (32.6%). Regarding the consumption of instant food or soda, the most common response was “similar,” reported by 33,047 respondents (44.4%). For drinking and smoking habits, “not applicable” was the most common response, but there were more reports of a decrease than an increase. The average score for each item was as follows: physical activity scored 2.45±0.72 and eating instant food scored 2.96±0.99, indicating a score distribution close to “similar to before COVID-19.” Drinking scored 3.40±0.85 and smoking scored 3.72±0.67, suggesting an overall score distribution close to “not applicable.”

- Concerns due to COVID-19

- Table 3 presents the results for concerns due to COVID-19. The most common response was “very much so” for the following concerns: “concerns about infection” with 27,507 (37.0%), “criticism from others” with 32,099 (43.2%), and “economic damage” with 37,701 (50.7%). This suggests that elderly individuals were highly concerned about COVID-19. When examining the average score for each item, the concern due to infection was 2.18±1.16, the concern due to economic damage was 1.94±1.06, and the concern due to criticism from others was 1.82±1.04. This indicates that the average distribution of scores ranged from “yes” to “very much so.”

- Depression and HRQOL

- In the depression assessment (PHQ-9), the item “difficulty falling asleep or sleeping too much” scored 0.63±0.96 points, while “tiredness and low energy” scored 0.59±0.79 points. These 2 items had the highest scores. In the HRQOL evaluation (EQ-5D), “self-care” had the highest score (1.15±0.39 points), while “pain/discomfort” had the lowest score (1.59±0.61 points) (Table 4).

- Depression and HRQOL according to General Characteristics

- Table 5 presents the results for depression and HRQOL in relation to general characteristics. Higher levels of depression were observed in women, individuals aged 85 years or older, those living alone due to the loss of a spouse, those not participating in economic activities, and those experiencing an increase in income and expenditure related to COVID-19 (p<0.001). In contrast, men aged between 65 and 75 years, those living separately from their spouses, those engaged in economic activities, and those experiencing a decrease in income and expenditure due to COVID-19 generally exhibited higher HRQOL (p<0.001). Among the subcategories of HRQOL, the “anxiety/depression” component did not appear to be associated with changes in income due to COVID-19 (p>0.05).

- Factors Affecting Depression and HRQOL

- A multiple regression analysis was performed to explore the impact of general characteristics and COVID-19-related concerns on depression and HRQOL in the elderly population. The independent variables were general characteristics and COVID-19-related concerns, while the dependent variables were depression and HRQOL. Upon examining the multi-collinearity among the variables influencing each variable, it was found that the variance inflation factor value was less than 10 for all variables, indicating no multi-collinearity issue. In terms of depression, the F value, which signifies the model’s suitability, was 361.983 (p<0.001), with R2=0.064 and an adjusted R2=0.064. For HRQOL, the F value indicating the model’s suitability was 1,212.218 (p<0.001), with R2=0.186 and an adjusted R2=0.186. All variables, except for those pertaining to individuals who were divorced and living alone, had an impact on depression. Concerns related to COVID-19, specifically worries about infection and economic damage, were also found to influence depression (p<0.05, p<0.01, p<0.001). All variables, except for those related to individuals living alone due to bereavement, had an impact on HRQOL. Concerns related to COVID-19 were found to influence HRQOL (p<0.05, p<0.01, p<0.001) (Table 6).

Results

- This study utilized data from the 2021 Community Health Survey to examine the changes in health behaviors among the elderly population due to COVID-19. It also explored their concerns related to COVID-19, depression, and HRQOL. The ultimate goal was to identify factors that influence depression and HRQOL among the elderly.

- Upon examining the changes in health behaviors among subjects due to COVID-19, it was found that many reported their physical activity levels to be similar to or less than those prior to the pandemic. When asked about their concerns related to COVID-19, the majority responded with “very much so” to all queries about infection fears, criticism from others, and economic damage. Notably, concerns about economic damage were the most prevalent. These growing fears about infection can cause older individuals to avoid social interactions, leading to increased social isolation [15]. The elderly are at a higher risk of disease exposure due to decreased immunity, and many also have chronic conditions. COVID-19, in particular, has a high fatality rate among older individuals with underlying health conditions [16]. This reality caused many elderly individuals to increasingly avoid outdoor activities due to infection fears, creating a vicious cycle that further deteriorated their physical functions.

- The number of responses indicating a decrease in income following the COVID-19 pandemic was approximately 20 times greater than those reporting an increase. There was a high level of concern about economic damage due to COVID-19, suggesting that the elderly may face financial hardship in the event of an infectious disease outbreak. A previous study found that 73.1% of respondents reported economic difficulties due to the impact of COVID-19. The majority of these respondents experienced financial hardship, with self-employed individuals, freelancers, day laborers, and the elderly from vulnerable groups suffering particularly severe difficulties [17]. The job project for the elderly, a component of the social participation program for this demographic, provided partial financial support to the elderly by disbursing a small amount of activity-related expenses each month. However, due to the suspension of this project amid the COVID-19 pandemic, many elderly individuals reported financial difficulties resulting from the loss of this income [4]. In 2020, the Seoul Welfare Foundation conducted a survey on lifestyle changes among Seoul citizens. Respondents reported difficulties related to changes in their income, including an inability to pay rent or utility bills, foregoing hospital visits due to costs, and issues that directly impact daily life, such as not being able to maintain a balanced diet [18]. The economic difficulties stemming from a decrease in children's income and the suspension of their own income are considered among the most significant concerns arising from the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The depression test results indicated high scores for sleep or fatigue-related issues, such as “difficulty falling asleep or sleeping too much” and “tiredness, low energy.” The highest HRQOL item was “self-care,” while the lowest was “pain/discomfort.” This suggests that while there was little difficulty in self-care, the HRQOL was negatively impacted by bodily pain and discomfort. Kim [19] conducted an analysis of the interactions among risk factors in elderly individuals whose physical activity had decreased due to COVID-19. The findings revealed that sleep disorders significantly influenced depression in the elderly, indicating a strong correlation between sleep disorders and depression. The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-5 has already established that depression and sleep disorders are closely linked, to the extent that sleep disorders are included in the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorders. A reduction in physical activity can lead to a deterioration in health status, and subsequent fatigue, loss of energy, physical pain, and difficulty sleeping can create a vicious cycle. Therefore, maintaining a positive perception of one's health is crucial.

- Depression rates were higher among women, older individuals, those living alone due to the loss of a spouse, those with no economic activity, and those experiencing significant changes in income and expenditure due to COVID-19. The analysis revealed that all these factors influenced depression. Generally, it is recognized that women have a higher incidence of depression than men, a fact that was also reflected in a study conducted post-COVID-19, which showed a higher risk of depression among elderly women compared to men [20]. Elderly individuals living alone have been found to experience higher levels of depression compared to those living with family, reinforcing the findings of this study and underscoring the importance of familial cohabitation in old age [21]. The respondents in this study cited economic difficulties as their primary concern due to COVID-19, suggesting a correlation between the increased expenditure brought on by the pandemic and depression.

- HRQOL was higher in older men, those living separately from a spouse, those engaged in economic activity, and those experiencing minimal changes in income and expenditure due to COVID-19. Upon analyzing the factors influencing HRQOL, it was found that all the aforementioned factors had a significant impact. Previous studies have suggested that having a spouse positively affects the mental health of the elderly. However, this study's results indicate that living separately from a spouse can lead to a higher HRQOL, warranting further discussion on the topic.

- In Republic of Korea, the rate of divorce among couples married for over 20 years is rapidly increasing, particularly among those aged 65 or older, a phenomenon referred to as “twilight divorce” [22]. These couples, who may have endured an incompatible marriage for the sake of their children, often seek divorce in their later years, dreaming of a second life. According to 2021 data, only 12.8% of elderly individuals expressed a desire to live with their grown children, a significant decrease from 32.5% in 2008 [23]. This suggests a shift towards a more independent lifestyle among the elderly. The higher HRQOL observed in those living alone without a spouse, maintaining steady economic activity, and experiencing minimal changes in spending due to COVID-19, can be seen as a reflection of this changing perception.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has also led to an increase in home-based work and study, resulting in families spending more time together, which has been associated with increased conflicts [24]. This suggests that while humans are social creatures, HRQOL may be higher when individuals have time to themselves. Factors influencing depression included concerns about infection and economic damage, while factors affecting HRQOL included concerns about infection, economic damage, and criticism from others. Fear of infection leads individuals to isolate themselves, potentially leading to a vicious cycle of continued isolation and deteriorating physical health. However, it is important to prioritize personal comfort and health maintenance, rather than forcing social interactions. Activities such as moderate-intensity outdoor walking at least 3 times a week and home-based stretching exercises are recommended for this purpose [25]. Regular walking, even without a specific exercise program, can effectively reduce depression in the elderly and improve HRQOL. For the elderly, who are more vulnerable to infection, concern about this issue is inevitable. Therefore, national and community-level interventions are needed to alleviate the concerns and stress of the elderly in the event of future infectious disease outbreaks. It is crucial to identify and provide tailored support to vulnerable elderly groups who may experience unstable emotions such as depression. Particularly, those over 75 years of age or those living alone, who are at high risk of emotional difficulties and social isolation, may benefit from support services such as home visits. Some dementia care centers and mental health welfare centers currently offer home visits once or twice a month to check on the health of the elderly and organize their home environment [26]. Additionally, many community organizations are planning to implement a service to check on the health of the elderly via phone calls on a weekly basis. If expanded, this system could greatly assist in managing the emotional health of the elderly. Therefore, services that monitor the elderly through home visits or phone calls should be expanded. As previously mentioned, providing information on affordable physical activities and emotional support services can help improve the HRQOL of the elderly.

- This study has certain limitations, primarily due to its reliance on raw data from the Community Health Survey, which restricted its ability to identify changes in all aspects of life. Additionally, it was not possible to consider more nuanced sociodemographic characteristics. Despite these constraints, this study successfully identified changes in the health behavior and concerns of the elderly population in Korea due to COVID-19. It also investigated the factors influencing depression and HRQOL. It also makes a significant contribution by proposing a strategy to support the mental health of the elderly.

Discussion

- This study investigated changes in the health behaviors of the elderly due to COVID-19, the current status of concerns due to COVID-19, depression, and HRQOL, and aimed to identify factors affecting depression and HRQOL in the elderly.

- The main results of the study were as follows: There was a high level of depression related to sleep and fatigue. In terms of HRQOL, the lowest scores were associated with physical pain and discomfort. Upon examining the impact of COVID-19-related concerns on depression and HRQOL among the elderly, it was discovered that increased concerns led to heightened depression and negatively affected HRQOL. In the event of future infectious disease outbreaks like COVID-19, priority should be given to early screening and support for those who are emotionally vulnerable. Participation in hybrid online and offline programs at senior welfare centers, community counseling institutions such as mental health welfare centers, and involvement in stable senior job projects should be encouraged to mitigate the effects of social interaction restrictions, physical and psychological health issues, and economic difficulties faced by the elderly.

Conclusion

HIGHLIGHTS

-

Ethics Approval

This data utilized the data from the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency’s 2021 Community Health Survey, and the Community Health Survey was conducted directly by the state for the public. Therefore, this research could be conducted without deliberation by the Research Ethics Committee.

-

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Funding

None.

-

Availability of Data

The datasets are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

Additional Contributions

The author appreciates the help from the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, to conduct the study using the 2021 Community Health Survey.

Article information

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19, 11 March 2020 [Internet]. WHO; 2020 [cited 2021 Oct 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

- 2. Kim Y, Oh SM. The impact of COVID-19 on cognitive function in older adults: focusing on the comparison between the older adults living alone and the non-living alone. Korean J Gerontol Soc Welf 2022;77:75−100. Korean.Article

- 3. Kwon OJ. A case study of changes in the exercise behavior of the elderly by COVID-19. Korean Soc Sport Psychol 2020;31:123−34. Korean.Article

- 4. Shin HR, Yoon TY, Kim SK, et al. An exploratory study on changes in daily life of the elderly amid COVID-19-focusing on technology use and restrictions on participation in elderly welfare centers. Korean J Gerontol Soc Welf 2020;75:207−32. Korean.Article

- 5. Song YS, Kim TB, Bae NK, et al. Relating factors on mental health status (depression, cognitive impairment and dementia) among the admitted from long-term care insurance. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc 2018;19:247−60. Korean.

- 6. Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:837−41.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Chan SM, Chiu FK, Lam CW, et al. Elderly suicide and the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;21:113−8.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Berg AI. Life satisfaction in late life: markers and predictors of level and change among 80+ year olds [dissertation] University of Gothenburg. 2008.

- 9. Kim JH, Jung YM. A study on the health age, activity daily of living and cognitive function of the elderly. J Korean Gerontol Nurs 2001;3:22−31. Korean.

- 10. Yoo BS, Lee KW. Change in ways of providing services at the senior welfare center based on COVID-19 coping strategies. Korean J Res Gerontol 2021;30:21−36. Korean.Article

- 11. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA). Community health survey 2021 guidelines for using raw data. KDCA; 2021. Korean.

- 12. Park SJ, Choi HR, Choi JH, et al. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Anxiety Mood 2010;6:119−24. Korean.

- 13. Seong SS, Choi CB, Sung YK, et al. Health-related quality of life using EQ-5D in Koreans. J Korean Rheum Assoc 2004;11:524−62. Korean.

- 14. Jo MW, Lee SI. Validity and reliability of Korean EQ-5D valuation study using the time-trade off method. Korean J Helth Promot 2007;7:96−103. Korean.

- 15. Meo SA, Alhowikan AM, Al-Khlaiwi T, et al. Novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV: prevalence, biological and clinical characteristics comparison with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020;24:2012−19.PubMed

- 16. Bae GE. An exploratory study on the effect of the prolonged COVID-19 on the daily life of the elderly: focusing on users of the elderly welfare center. J Korea Soc Wellness 2022;17:1−13. Korean.Article

- 17. Son BD, Moon HJ. Who suffers the most financial hardships due to COVID-19? Korean J Soc Welf 2021;73:9−31. Korean.Article

- 18. Moon HJ, Ku I, Kim JS, et al. A study on performance evaluation of disaster emergency living expenses in Seoul. Seoul Welfare Foundation; 2020. Korean.

- 19. Kim CJ. Analysis of depression due to change in the physical activities of older adults: focusing on the impact of COVID-19. Korean J Adapt Phys Act 2022;30:89−101. Korean.

- 20. Moon JH, Kim SJ, Sung KO. An exploratory study on COVID-19 phobia and influencing factors. Soc Sci Res 2021;32:285−307. Korean.Article

- 21. Kim HK, Lee HJ, Park SM. Factors influencing quality of life in elderly women living alone. J Korean Gerontol Soc 2010;30:279−92. Korean.

- 22. Lee HS. A case study on the elderly woman who has divorced. Korean J Gerontol Soc Welf 2015;68:85−106. Korean.

- 23. 8 out of 10 elderly, ‘live separately from their children’… A changing elderly generation. The Kyunghyang Shinmun [Internet]. 2021 Jun 7 [cited 2023 Sep 26]. Available from: https://www.khan.co.kr/print.html?art_id=202106071117001. Korean.

- 24. ‘Extension and extension’… The trend of 'COVID-19 telecommuting' in large corporations is prolonged. The Korea Economy [Internet]. 2020 Mar 14 [cited 2023 Sep 26]. Available from: https://www.hankyung.com/economy/article/202003140737Y. Korean.

- 25. Stanton R, Reaburn P. Exercise and the treatment of depression: a review of the exercise program variables. J Sci Med Sport 2014;17:177−82.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Chungbuk Metropolitan Dementia Center. Memory keeper guide book. Chungbuk Metropolitan Dementia Center; 2019. Korean.

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Cite

Cite