Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Osong Public Health Res Perspect > Volume 11(2); 2020 > Article

-

Original Article

Cross-Country Comparison of Case Fatality Rates of COVID-19/SARS-COV-2 - Morteza Abdullatif Khafaiea, Fakher Rahimb

-

Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives 2020;11(2):74-80.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.2.03

Published online: April 30, 2020

aSocial Determinants of Health Research Center, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

bHealth Research Institute, Research Center of Thalassemia and Hemoglobinopathies, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

- *Corresponding author: Fakher Rahim, Health Research Institute, Research Center of Thalassemia and Hemoglobinopathies, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran, E-mail: bioinfo2003@gmail.com

• Received: March 13, 2020 • Revised: March 23, 2020 • Accepted: March 23, 2020

Copyright ©2020, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Abstract

-

Objectives

- Case fatality rates (CFR) and recovery rates are important readouts during epidemics and pandemics. In this article, an international analysis was performed on the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

-

Methods

- Data were retrieved from accurate databases according to the user’s guide of data sources for patient registries, CFR and recovery rates were calculated for each country. A comparison of CFR between countries with total cases ≥ 1,000 was observed for 12th and 23rd March.

-

Results

- Italy’s CFR was the highest of all countries studied for both time points (12th March, 6.22% versus 23rd March, 9.26%). The data showed that even though Italy was the only European country reported on 12rd March, Spain and France had the highest CFR of 6.16 and 4.21%, respectively, on 23rd March, which was strikingly higher than the overall CFR of 3.61%.

-

Conclusion

- Obtaining detailed and accurate medical history from COVID-19 patients, and analyzing CFR alongside the recovery rate, may enable the identification of the highest risk areas so that efficient medical care may be provided. This may lead to the development of point-of-care tools to help clinicians in stratifying patients based on possible requirements in the level of care, to increase the probabilities of survival from COVID-19 disease.

- A novel coronavirus has spread through China, originating from the city of Wuhan and has caused many deaths so far. It is a highly contagious virus that has spread rapidly and efficiently. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by a virus (SARS-CoV-2) from the same family as the lethal coronaviruses that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV). COVID-19 is a relatively large virus (120 nm) and is enveloped, containing a positive-sense single-stranded RNA [1]. The virus is transmitted through direct contact with the infected person’s respiratory droplets (coughing and sneezing), as well as contact with infected surfaces. COVID-19 virus can survive for days on surfaces, but a simple disinfectant can eliminate this [2]. COVID-19 signs and symptoms include fever, cough, and shortness of breath. In more severe cases, infection can lead to pneumonia, serious respiratory problems and ultimately, fatalities. Thousands of people have been reported to have been infected with the virus so far [3]. Apart from China, other cases of the disease, also known as COVID-2, have been reported in several countries, including Thailand, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Australia, Iran, and the United States. According to the Worldometer, as of 10th March 2020, there are over 114,430 identified cases of COVID-19 worldwide in 115 countries and territories [1].

- Of these 115 countries, South Korea and Iran (outside of China) have the largest epidemic of COVID-19 and Italy, France and Spain are the countries with a major epidemic of COVID-19 in Europe [2]. COVID-19 spreads mainly from person-to-person during the latency period before the symptoms appear [4]. There is much more to learn about the spread and severity of COVID-19. COVID-19 can cause mild flu-like symptoms, including fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia, and fatigue, while more serious forms can cause severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock, and organ failure, which can lead to death [5]. Without a vaccine for COVID-19, transmission of the virus can be reduced with early detection and patient quarantine [6]. There is epidemiological and clinical evidence to suggest a number of novel compounds, as well as medicines licensed for other conditions, that appear to have potential efficacy against COVID-19 [7,8]. However, in the absence of a safe and effective vaccine or medicine, reducing viral transmission is the only strategy available where general education, and implementing the appropriate prevention and control is key. Precautions can help suppress the risk of infection, such as washing the hands frequently with soap and water or an alcohol-based disinfectant gel, coughing into the elbow or a folded napkin/tissue, avoiding close contact with those who have symptoms, and self-isolating, but medical help must be sought if difficulty in breathing is experienced [5].

- COVID-19 can be diagnosed with diagnostic test kits [9] and imaging techniques such as chest X-ray and pulmonary CT scans that facilitate early diagnosis of pneumonia in patients with COVID-19 [10–12].

- The case fatality rate (CFR), is a measure of the ability of a pathogen or virus to infect or damage a host in infectious disease and is described as the proportion of deaths within a defined population of interest, i.e. the percentage of cases that result in death [13]. CFRs confers the extent of disease severity and CFR is necessary for setting priorities for public health in targeted interventions to reduce the severity of risk [14]. Initial studies reported an estimation of 3% for the global CFR of COVID-19 [15]. Estimating CFR from country-level data requires assessment of information about the delay between the report of the country-specific cases and death from COVID-19, as well as underestimating and under-reporting of death-related cases, which may not be known. Given the importance of CFR and recovery rate (RR), in this current study the CFR and RR of different countries during a COVID-19 ongoing pandemic was observed using up-to-date country-level data.

Introduction

- 1. Source of data and procedure

- The data were retrieved from accurate databases including Worldometer 2, WHO 3, the Center of Disease Control and Prevention [16], and the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report series (provided from Center of Disease Control and Prevention), according to the user’s guide of data sources for patient registries [17]. Due to the rapid increase in data, the analysis in this study was performed on the 12th and 23rd of March 2020.

- Raw data was mapped according to countries and CFR and RR were compared for countries with ≥ 1,000 cases. All countries with < 1,000 cases are presented in supplementary Table 1. A comparison of CFR with different known viral diseases was performed.

- 2. Measuring the CFR and RR

- The formulas below were used to measure CFR and RR.

Materials and Methods

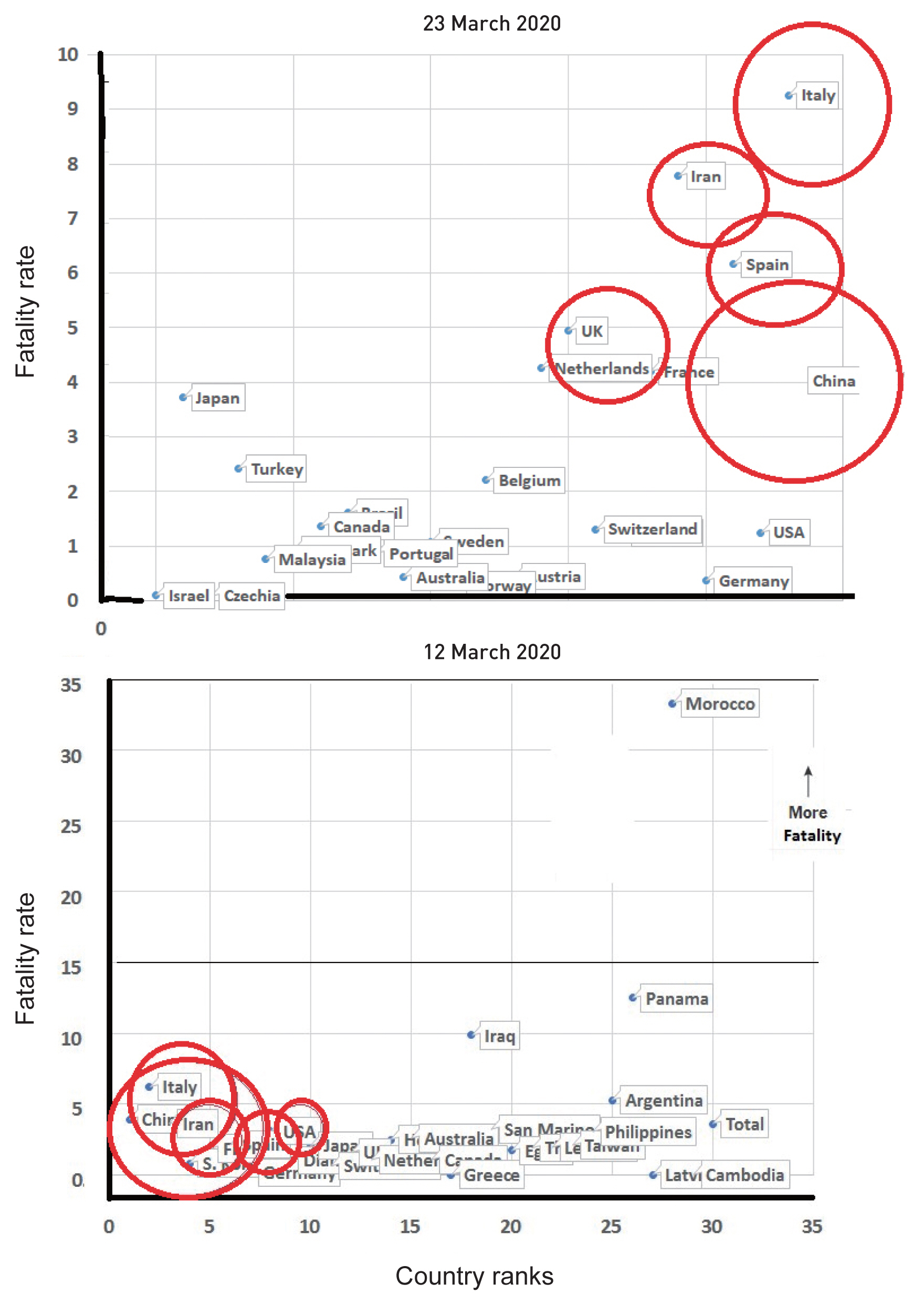

- The total number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 was highest in China, followed by Italy and Iran on 12th March, but on 23rd March 2020, total COVID-19 confirmed cases was the highest in China, followed by Italy, USA, and Spain (Table 1). However, Italy’s CFR was the highest on both time points (12th March, 6.22% versus 23rd March, 9.26%). The data showed that Italy was the only European country reported on 12th March, but by the 23rd March 2020, Spain and France had the highest CFR of 6.16 and 4.21%, respectively, which was strikingly higher than the overall CFR of 3.61%. The highest RR was observed in China, with RR values of 76.12% and 89.85% in both analysis time points, respectively, compared with the overall RR of 55.83% and 29.3% on the 12th and 23rd March 2020, respectively.

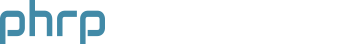

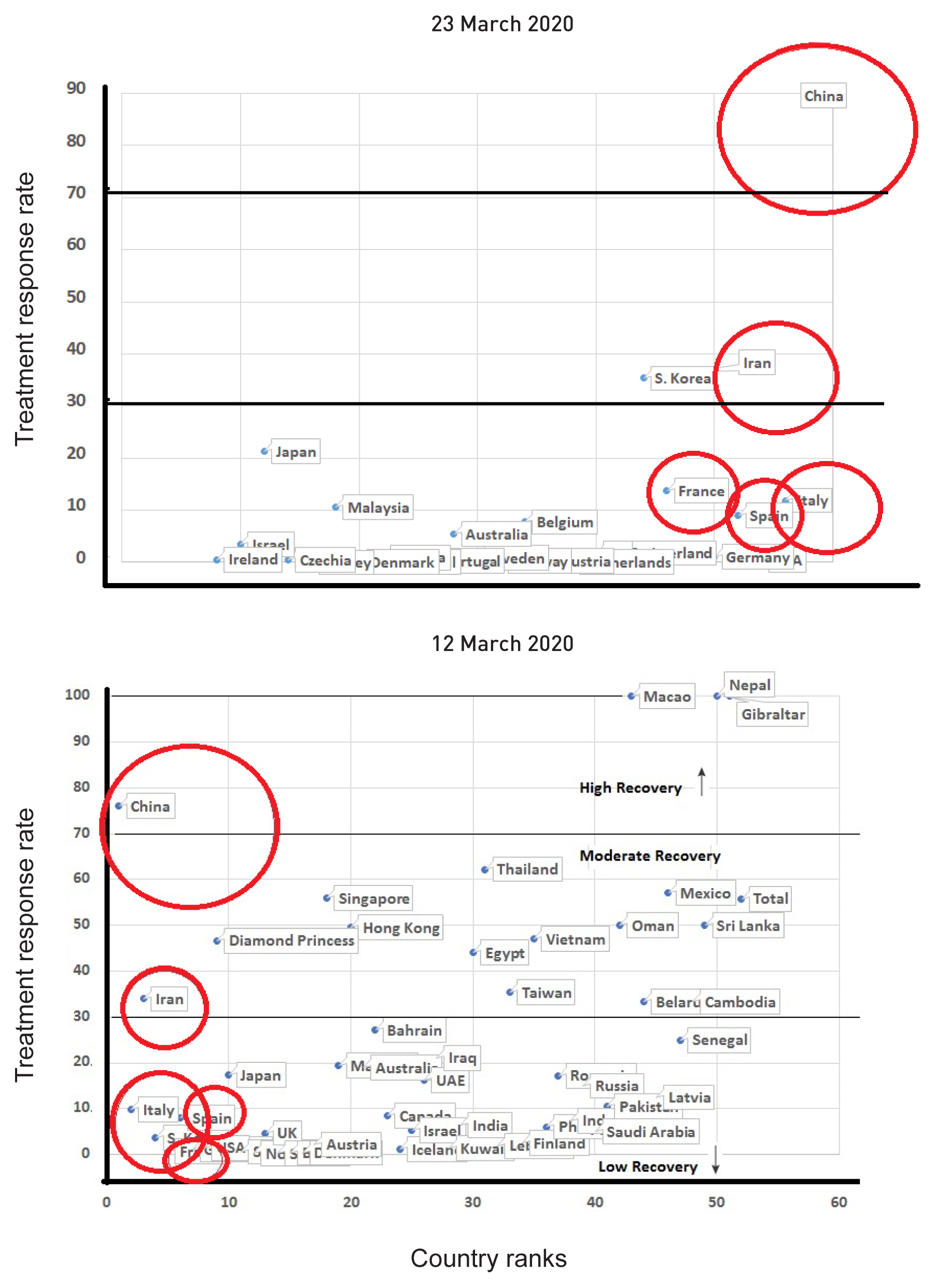

- The highest CFR was observed in Italy, followed by China, Iran, and USA on 12th March, which changed to Italy, Spain, France, Iran, and China on 23rd March (Figure 1). Among European countries, Spain and France also faced an increasing rate of CFR. Although Morocco, Panama, and Iraq showed higher CFR values, there was only a small number of total cases, therefore the results of countries with highest outbreak and total cases of COVID-19 were preferentially reported.

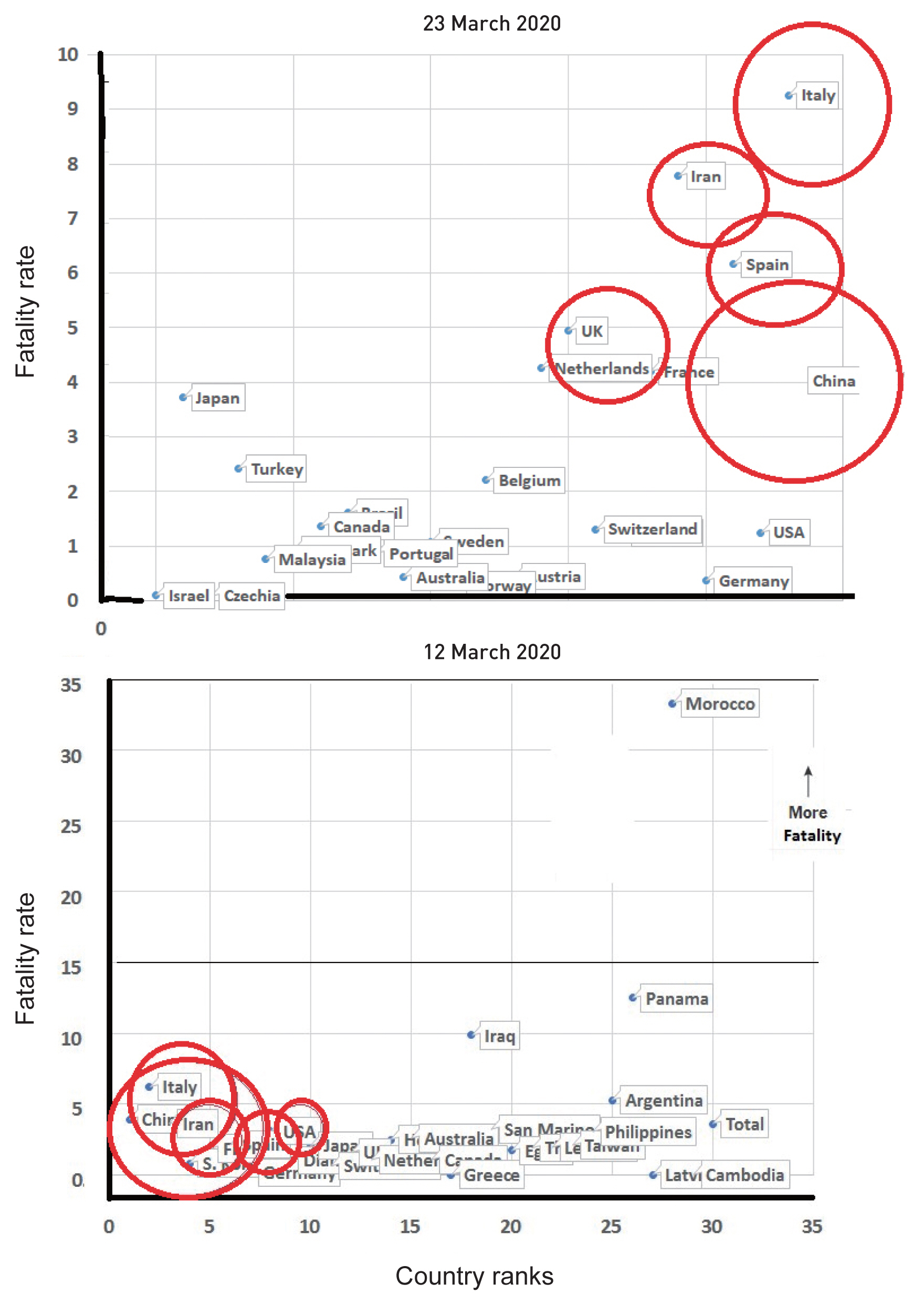

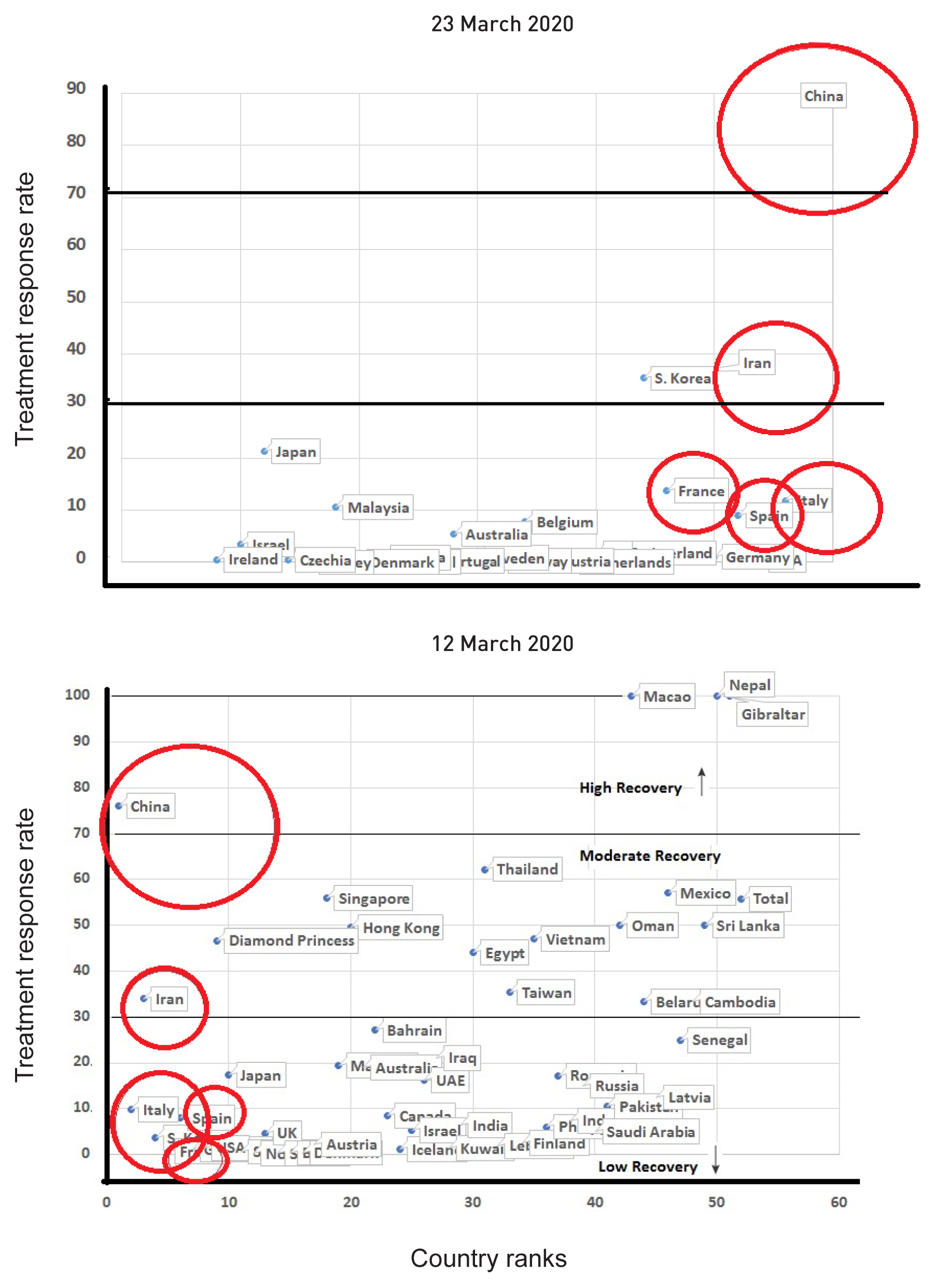

- China showed encouraging recovery rates from COVID-19 at both time points (76.12% and 89.85% on 12th and 23rd March 2020, respectively; Figure 2). Although the COVID-19 outbreak has led to high rates of death in other Asian countries such as Iran, the recovery rate may be considered acceptable (34%).

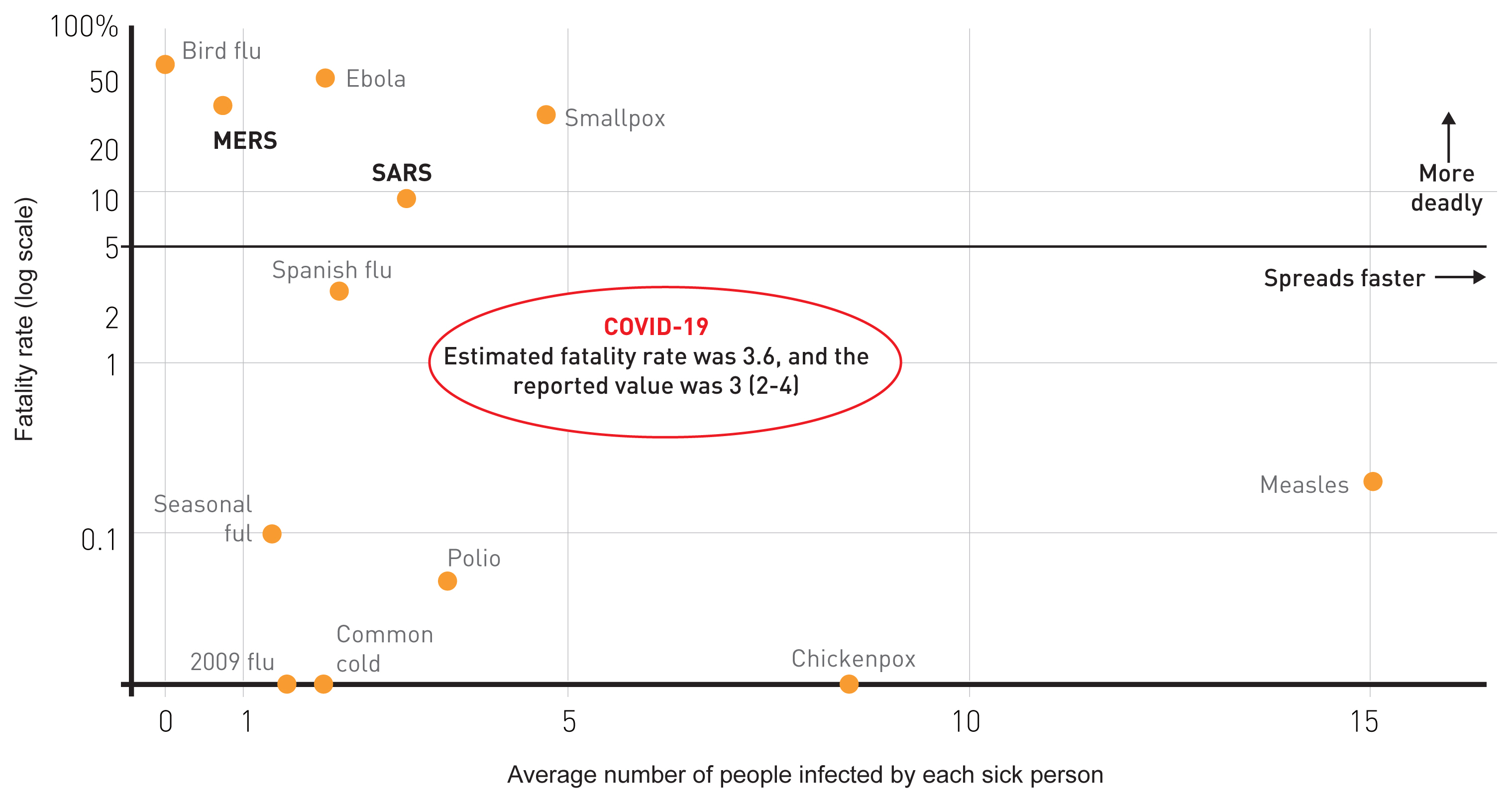

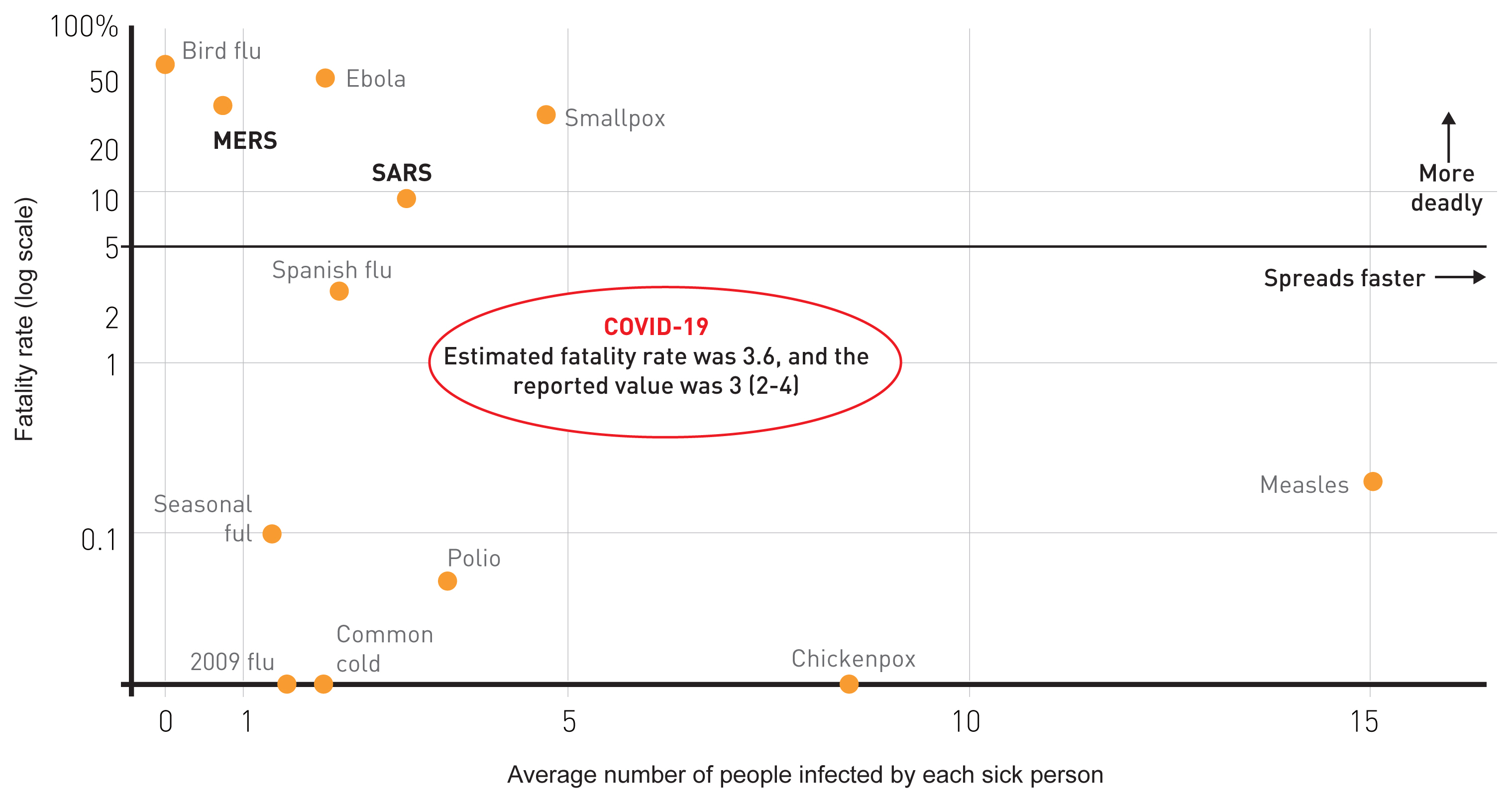

- The comparison of CFR between different known infectious and viral diseases was shown in Figure 3. This revealed that the overall clinical concerns of COVID-19 may eventually be more like those of a severe seasonal flu (CFR of approximately 0.1%) or a pandemic flu, rather than SARS or MERS, which have had CFR of approximately 10% and 36%, correspondingly.

Results

- This study aimed to observe the CFR of different countries during an ongoing COVID-19 pandemic using recent country-level data, showing that alongside the outbreak of this virus, there is a frame-shift and transition from China (as the first country faced with the outbreak) to other countries in other continents.

- The outbreak was declared a public health emergency of international concern on 30th January 2020 [18]. Confronting emerging diseases requires universal cooperation in identifying, controlling, and preventing these diseases. The Center for Disease Control obtained a number of factors to establish a geographic risk assessment for the spread of COVID-19 (Supplementary Figure 1). This may be used for international guidelines for public health decisions and travel-related exposure. For instance, China and Iran were categorized as countries where there was widespread ongoing transmission, with restrictions on entry.

- The data from this study supports the fact that the CFR of the COVID-19 pandemic seems to be less than Bird flu, Ebola, SARS, and MERS, but public health concerns remain due to its highly infectious nature, since a large proportion of cases are asymptomatic or mild, which promotes the spread of the disease worldwide. In such situations, the media plays a crucial role in promoting health literacy and advocating limited spread of the disease [19]. Cross-country comparisons of CFR and RR as important indicators of disease characteristics are vital for national and international priority setting and recognizing health system performance. However, many factors can confound the current estimation for CFR and RR of COVID-19, namely, undetected cases or delayed case reporting, which can significantly affect the 2 indicators which are linked with a degree of preparedness and mitigation of both the general public and politicians.

- Since the number of cases in the world is increasing in a heterogeneous form, to obtain a better picture for cross-country compression of medical care performance, we require a limiting denominator of CFR and RR to be applied to cases under official medical care with final disease outcome (death/ recovered or discharged).

Discussion

- Death and severity of COVID-19 are associated with age and comorbidities across the world. Especially in countries with the highest outbreaks, such as China, Italy, and Iran, strategies must be employed to ensure that high-risk groups, such as old people and those with other underlying diseases such as diabetes and cancer, received adequate protection from COVID-19. Therefore, early access to medical care when infected is vital for improving chances of survival. Improving medical supplies to countries such as Iran, which is significantly influenced by US punitive policies, can reduce the deterioration of this politically sensitive situation [20].

- Furthermore, taking detailed and accurate medical history, and scoring CFR alongside RR, may highlight the highest risk areas, and more efficiently direct the intervention to decrease the spread of the virus globally. This may enable the development of point-of-care tools to help clinicians in stratifying patients, based on possible requirements in the level of care to improve probabilities of survival from COVID-19 disease.

Conclusion

Supplementary Information

-

Acknowledgements

- We acknowledge the contribution made by Dr. Asaad Sharhani, Department of Statistics and epidemiology at Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, in data collection and data management.

Acknowledgments

- 1. Worlometers [Internet]. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic 2020 Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

- 2. World Health Organization [Internet]. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report - 43 Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200303-sitrep-43-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=2c21c09c_2.

- 3. Xu XW, Wu XX, Jiang XG, et al. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: Retrospective case series. BMJ 2020;368:m606PMID: 10.1136/bmj.m606. PMID: 32075786.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, et al. The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application. Ann Intern Med 2020;[Epub ahead of print]. Epub 2020 Mar 10. PMID: 10.7326/M20-0504. PMID: 32150748. PMID: 7081172.Article

- 5. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;[Epub ahead of print]. Epub 2020 Mar 6. PMID: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. PMID: 32109013.Article

- 6. Jernigan DB. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Update: Public Health Response to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak - United States, February 24, 2020. MMWR 2020;69(8). 216−9. PMID: 32106216.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Pang J, Wang MX, Ang IYH, et al. Potential Rapid Diagnostics, Vaccine and Therapeutics for 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): A Systematic Review. J Clin Med 2020;9(3). E623PMID: 10.3390/jcm9030623. PMID: 32110875.Article

- 8. Zhang L, Liu Y. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: A systematic review. J Med Virol 2020;92(5). 479−90. PMID: 10.1002/jmv.25707. PMID: 32052466.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Yi Li Z, Luo YX, et al. Development and Clinical Application of A Rapid IgM-IgG Combined Antibody Test for SARS-CoV-2 Infection Diagnosis. J Med Virol 2020;[Epub ahead of print]. Epub 2020 Feb 27.

- 10. Yang XH, Sun RH, Chen DC. Diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19: Acute kidney injury cannot be ignored. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2020;100(0). E017[in Chinese]. PMID: 32145717.

- 11. Xia W, Shao J, Guo Y, et al. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infection: Different points from adults. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020;[Epub ahead of print]. Epub 2020 Mar 05. PMID: 10.1002/ppul.24718. PMID: 32134205.Article

- 12. Zhao W, Zhong Z, Xie X, Yu Q, Liu J. Relation Between Chest CT Findings and Clinical Conditions of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pneumonia: A Multicenter Study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020;[Epub ahead of print]. Epub 2020 Mar 3. PMID: 10.2214/AJR.20.22976. PMID: 32125873.Article

- 13. Kanchan T, Kumar N, Unnikrishnan B. Mortality: Statistics. Encyclopedia of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 2nd ed.Elsevier Inc; 2015. pp 572−7.Article

- 14. Reich NG, Lessler J, Cummings DAT, Brookmeyer R. Estimating absolute and relative case fatality ratios from infectious disease surveillance data. Biometrics 2012;68(2). 598−606. PMID: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01709.x. PMID: 22276951. PMID: 4540071.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020;395(10223). 470−3. PMID: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. PMID: 31986257.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. Cases in U. S. 2020 Mar 23 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-in-us.html.

- 17. Gliklich RE, Dreyer NA, Leavy MB. [Internet] Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide 3rd ed. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2014 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK208611/.

- 18. Eurosurveillance editorial team. Note from the editors: World Health Organization declares novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) sixth public health emergency of international concern. Euro Surveill 2020;25(5). 200131ePMID: 7014669.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Mojadam M, Matlabi M, Haji A, et al. Khuzestan dust phenomenon: A content analysis of most widely circulated newspapers. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2018;25:15918−24. PMID: 10.1007/s11356-018-1833-5.ArticlePDF

- 20. Takian A, Raoofi A, Kazempour-Ardebili S. COVID-19 battle during the toughest sanctions against Iran. Lancet 2020;[Epub ahead of print]. Epub 2020 Mar 18. PMID: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30668-1. PMID: 32199073.Article

References

Figure 1The cross-country comparison of case fatality rate (CFR) between different countries (n = 116). The circles showed the countries with highest outbreak and positive cases of COVID-19. Countries with CFR value zero has not been illustrated here.

Figure 2The cross-country comparison of recovery rate (RR) between different countries (n = 116). The circles showed the countries with highest outbreak and positive cases of COVID-19. Countries with RR value zero has not been illustrated here.

Figure 3The cross-country comparison of case fatality rate (CFR) between different known infectious and viral diseases (n = 116). The circles showed the estimated value and the reported range of CFR of COVID-19.

Table 1The comparison of case fatality rate (CFR) and recovery rate (RR) between different countries (n = 116). Only countries with total cases over 1,000 cases depicted (population in million and GDP in trillion USD; n = 116).

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Social and Spatial Inequalities during COVID-19: Evidence from France and the Need for a New Sustainable Urban and Regional Development Paradigm

Roula Maya

Sustainability.2024; 16(8): 3501. CrossRef - Impact of pandemic on development and demography in different continents and nations

Pawan Kumar Singh, Alok Kumar Pandey, Ravi Kiran, Rajiv Kumar Bhatt, Anushka Chouhan

International Journal of Finance & Economics.2023; 28(3): 3119. CrossRef - Inhibition of the predicted allosteric site of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease through flavonoids

Bibi Kubra, Syed Lal Badshah, Shah Faisal, Mohamed Sharaf, Abdul-Hamid Emwas, Mariusz Jaremko, Mohnad Abdalla

Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics.2023; 41(18): 9103. CrossRef - The Probable Protective Effect of Photobiomodulation on the Immunologic Factor’s mRNA Expression Level in the Lung: An Extended COVID-19 Preclinical and Clinical Meta-analysis

Babak Arjmand, Fakher Rahim

Clinical Pathology.2023; 16: 2632010X2211276. CrossRef - Applying Machine Learning to Healthcare Operations Management: CNN-Based Model for Malaria Diagnosis

Young Sik Cho, Paul C. Hong

Healthcare.2023; 11(12): 1779. CrossRef - Resilience strengthening of tuberculosis diagnostic services under national tuberculosis program to withstand pandemic situations

Sarika Jain, Monil Singhai, Vineet Chadha, N. Somashekar

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences.2023; 75: 94. CrossRef - An Assessment on Health And COVID-19 Indicators of OECD Countries

Mustafa FİLİZ

Turkish Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Car.2023; 17(3): 338. CrossRef - A comparison of symptom management and utilization of specialist palliative care in the early COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-site retrospective chart review

Madelaine Baetz-Dougan, Jennifer Guan, Blair Henry, Kalli Stilos, Desmond Leung, Niren Shetty, Shruti Gupta, Anita Chakraborty

Progress in Palliative Care.2023; 31(6): 333. CrossRef - Psychological impact of COVID-19 and determinants among Spanish university students

Jesús Cebrino, Silvia Portero de la Cruz

Frontiers in Public Health.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - Uncovering the impact of COVID-19 on the place of death of cancer patients in South America

Doris Durán, Renzo Calderon Anyosa, Belinda Nicolau, Jay S. Kaufman

Cadernos de Saúde Pública.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - COVID-19 and cardiovascular diseases: Past, present, and future

Barun Kumar, Abhimanyu Nigam, Shishir Soni, Vikas Kumar, Anupam Singh, Omna Chawla

Journal of Cardio-diabetes and metabolic disorders.2022; 2(2): 41. CrossRef - Examining the geographic distribution of six chronic disease risk factors for severe COVID-19: Veteran–nonveteran differences

Michelle McDaniel, Justin T McDaniel

Chronic Illness.2022; 18(3): 666. CrossRef - Suicidal Ideation during the COVID-19 Pandemic among A Large-Scale Iranian Sample: The Roles of Generalized Trust, Insomnia, and Fear of COVID-19

Chung-Ying Lin, Zainab Alimoradi, Narges Ehsani, Maurice M. Ohayon, Shun-Hua Chen, Mark D. Griffiths, Amir H. Pakpour

Healthcare.2022; 10(1): 93. CrossRef - COVID-19 and Sanctions Affecting Afghans in Iran

Athar Shafaei, Karen Block

Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies.2022; : 1. CrossRef - Heterogeneity of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States of America: A Geo-Epidemiological Perspective

Alexandre Vallée

Frontiers in Public Health.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - COVID-19 mortality, excess mortality, deaths per million and infection fatality ratio, Belgium, 9 March 2020 to 28 June 2020

Geert Molenberghs, Christel Faes, Johan Verbeeck, Patrick Deboosere, Steven Abrams, Lander Willem, Jan Aerts, Heidi Theeten, Brecht Devleesschauwer, Natalia Bustos Sierra, Françoise Renard, Sereina Herzog, Patrick Lusyne, Johan Van der Heyden, Herman Van

Eurosurveillance.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Assessing the impact of temperature and humidity exposures during early infection stages on case-fatality of COVID-19: A modelling study in Europe

Jingbo Liang, Hsiang-Yu Yuan

Environmental Research.2022; 211: 112931. CrossRef - The Analysis of Turkey’s Fight Against the COVID-19 Outbreak Using K-Means Clustering and Curve Fitting

Fatih Ahmet Şenel

Vietnam Journal of Computer Science.2022; 09(01): 19. CrossRef - China's COVID-19 Control Strategy and Its Impact on the Global Pandemic

Difeng Ding, Ruilian Zhang

Frontiers in Public Health.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Generalized Susceptible–Exposed–Infectious–Recovered model and its contributing factors for analysing the death and recovery rates of the COVID-19 pandemic

Felin Wilta, Allyson Li Chen Chong, Ganeshsree Selvachandran, Ketan Kotecha, Weiping Ding

Applied Soft Computing.2022; 123: 108973. CrossRef - Is there an association between COVID-19 mortality and Human development index? The case study of Nigeria and some selected countries

Sanyaolu Alani Ameye, Temitope Olumuyiwa Ojo, Tajudin Adesegun Adetunji, Michael Olusesan Awoleye

BMC Research Notes.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Modeling for the Stringency of Lock-Down Policies: Effects of Macroeconomic and Healthcare Variables in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Giunio Santini, Mario Fordellone, Silvia Boffo, Simona Signoriello, Danila De Vito, Paolo Chiodini

Frontiers in Public Health.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - The association between different predictive biomarkers and mortality of COVID-19

Narges Ansari, Mina Jahangiri, Kimia Shirbandi, Mina Ebrahimi, Fakher Rahim

Bulletin of the National Research Centre.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Association of COVID-19 Case-Fatality Rate With State Health Disparity in the United States

Yu-Che Lee, Ko-Yun Chang, Mehdi Mirsaeidi

Frontiers in Medicine.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Leveraging the therapeutic, biological, and self-assembling potential of peptides for the treatment of viral infections

Maya K. Monroe, Han Wang, Caleb F. Anderson, Hongpeng Jia, Charles Flexner, Honggang Cui

Journal of Controlled Release.2022; 348: 1028. CrossRef - COVID-19 Mortality and Related Comorbidities in Hospitalized Patients in Bulgaria

Rositsa Dimova, Rumyana Stoyanova, Vesela Blagoeva, Momchil Mavrov, Mladen Doykov

Healthcare.2022; 10(8): 1535. CrossRef - COVID-19 trends, public restrictions policies and vaccination status by economic ranking of countries: a longitudinal study from 110 countries

Myung-Bae Park, Chhabi Lal Ranabhat

Archives of Public Health.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Impact of Immunotherapies on SARS-CoV-2-Infections and Other Respiratory Tract Infections during the COVID-19 Winter Season in IBD Patients

Constanze Heike Waggershauser, Cornelia Tillack-Schreiber, Paul Weyh, Eckard Alt, Thorsten Siegmund, Christine Berchthold-Benchieb, Daniel Szokodi, Fabian Schnitzler, Thomas Ochsenkühn, Alessandro Granito

Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatolog.2022; 2022: 1. CrossRef - Epidemiological features of COVID-19 in Iran

Negah Tavakolifard, Mina Moeini, Asefeh Haddadpoor, Zahra Amini, Kamal Heidari, Mostafa Rezaie

Journal of Research in Medical Sciences.2022; 27(1): 75. CrossRef - MULTIMOORA ile En İyi Makine Öğrenimi Algoritmasının Seçimi ve Covid-19 Pandemisi için Dünya Çapında Ülke Kümelerinin Belirlenmesi

Sevgi ABDALLA, Özlem ALPU

European Journal of Science and Technology.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Global variations in the burden of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its outcomes in pregnant women by geographical region and country’s income status: a meta-analysis

Jameela Sheikh, Heidi Lawson, John Allotey, Magnus Yap, Rishab Balaji, Tania Kew, Elena Stallings, Dyuti Coomar, Andrea Gaetano-Gil, Javier Zamora, Shakila Thangaratinam

BMJ Global Health.2022; 7(11): e010060. CrossRef - Predictive Model for National Minimal CFR during Spontaneous Initial Outbreak of Emerging Infectious Disease: Lessons from COVID-19 Pandemic in 214 Nations and Regions

Xiaoli Wang, Lin Fan, Ziqiang Dai, Li Li, Xianliang Wang

International Journal of Environmental Research an.2022; 20(1): 594. CrossRef - A Statistical Analysis and Comparison of the spread of Swine Flu and COVID-19 in India

Hari Murthy, Boppuru Rudra Prathap, Mani Joseph P, Vinay Jha Pillai, Sarath Chandra K, Kukatlapalli Pradeep Kumar

Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences.2022; 18(6): 92. CrossRef - More than just a common cold: Endemic coronaviruses OC43, HKU1, NL63, and 229E associated with severe acute respiratory infection and fatality cases among healthy adults

Ana B. Gorini da Veiga, Letícia G. Martins, Irina Riediger, Alix Mazetto, Maria do Carmo Debur, Tatiana S. Gregianini

Journal of Medical Virology.2021; 93(2): 1002. CrossRef - Emergence of European and North American mutant variants of SARS‐CoV‐2 in South‐East Asia

Ovinu Kibria Islam, Hassan M. Al‐Emran, Md. Shazid Hasan, Azraf Anwar, Md. Iqbal Kabir Jahid, Md. Anwar Hossain

Transboundary and Emerging Diseases.2021; 68(2): 824. CrossRef - Automated analysis of fatality rates for COVID 19 across different countries

Shaima Ibraheem Jabbar

Alexandria Engineering Journal.2021; 60(1): 521. CrossRef - Tocilizumab use in patients with moderate to severe COVID‐19: A retrospective cohort study

Sridhar Chilimuri, Haozhe Sun, Ahmed Alemam, Kyoung‐Sil Kang, Peter Lao, Nikhitha Mantri, Lawrence Schiller, Myroslava Sharabun, Elona Shehi, Jairo Tejada, Alla Yugay, Suresh Kumar Nayudu

Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics.2021; 46(2): 440. CrossRef - COVID-19 recovery rate and its association with development

Akancha Singh, Aparajita Chattopadhyay

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences.2021; 73: 8. CrossRef - Compositional diversity and evolutionary pattern of coronavirus accessory proteins

Jingzhe Shang, Na Han, Ziyi Chen, Yousong Peng, Liang Li, Hangyu Zhou, Chengyang Ji, Jing Meng, Taijiao Jiang, Aiping Wu

Briefings in Bioinformatics.2021; 22(2): 1267. CrossRef - Vitamin D Status in Hospitalized Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection

José L Hernández, Daniel Nan, Marta Fernandez-Ayala, Mayte García-Unzueta, Miguel A Hernández-Hernández, Marcos López-Hoyos, Pedro Muñoz-Cacho, José M Olmos, Manuel Gutiérrez-Cuadra, Juan J Ruiz-Cubillán, Javier Crespo, Víctor M Martínez-Taboada

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.2021; 106(3): e1343. CrossRef - Use of powered air-purifying respirator(PAPR) as part of protective equipment against SARS-CoV-2-a narrative review and critical appraisal of evidence

Ana Licina, Andrew Silvers

American Journal of Infection Control.2021; 49(4): 492. CrossRef - Postmortem Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in Nasopharyngeal Mucosa

Fabian Heinrich, Kira Meißner, Felicia Langenwalder, Klaus Püschel, Dominik Nörz, Armin Hoffmann, Marc Lütgehetmann, Martin Aepfelbacher, Eric Bibiza-Freiwald, Susanne Pfefferle, Axel Heinemann

Emerging Infectious Diseases.2021; 27(1): 329. CrossRef - COVID-19 caseness: An epidemiologic perspective

Abdel-Hady El-Gilany

Journal of Infection and Public Health.2021; 14(1): 61. CrossRef - Why are ACE2 binding coronavirus strains SARS‐CoV/SARS‐CoV‐2 wild and NL63 mild?

Puneet Rawat, Sherlyn Jemimah, P. K. Ponnuswamy, M. Michael Gromiha

Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics.2021; 89(4): 389. CrossRef - COVID-19 case fatality rates across Southeast Asian countries (SEA): a preliminary estimate using a simple linear regression model

George R Puno, Rena Christina C Puno, Ida V Maghuyop

Journal of Health Research.2021; 35(3): 286. CrossRef - Low-Dose Radiation Therapy for COVID-19: Promises and Pitfalls

Bhanu P Venkatesulu, Scott Lester, Cheng-En Hsieh, Vivek Verma, Elad Sharon, Mansoor Ahmed, Sunil Krishnan

JNCI Cancer Spectrum.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Professional football clubs and empirical evidence from the COVID-19 crisis: Time for sport entrepreneurship?

Jonas Hammerschmidt, Susanne Durst, Sascha Kraus, Kaisu Puumalainen

Technological Forecasting and Social Change.2021; 165: 120572. CrossRef - In silico validation of potent phytochemical orientin as inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 spike and host cell receptor GRP78 binding

Arijit Bhowmik, Souradeep Biswas, Subhadip Hajra, Prosenjit Saha

Heliyon.2021; 7(1): e05923. CrossRef - SARS-CoV-2 Mediated Endothelial Dysfunction: The Potential Role of Chronic Oxidative Stress

Ryan Chang, Abrar Mamun, Abishai Dominic, Nhat-Tu Le

Frontiers in Physiology.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - The Profile of the Obstetric Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection According to Country of Origin of the Publication: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Yolanda Cuñarro-López, Pilar Pintado-Recarte, Ignacio Cueto-Hernández, Concepción Hernández-Martín, María Pilar Payá-Martínez, María del Mar Muñóz-Chápuli, Óscar Cano-Valderrama, Coral Bravo, Julia Bujan, Melchor Álvarez-Mon, Miguel A. Ortega, Juan Antoni

Journal of Clinical Medicine.2021; 10(2): 360. CrossRef - Depressive Symptoms, Fatigue and Social Relationships Influenced Physical Activity in Frail Older Community-Dwellers during the Spanish Lockdown due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Laura M. Pérez, Carmina Castellano-Tejedor, Matteo Cesari, Luis Soto-Bagaria, Joan Ars, Fabricio Zambom-Ferraresi, Sonia Baró, Francisco Díaz-Gallego, Jordi Vilaró, María B. Enfedaque, Paula Espí-Valbé, Marco Inzitari

International Journal of Environmental Research an.2021; 18(2): 808. CrossRef - A knowledge gap unmasked: viral transmission in surgical smoke: a systematic review

Connal Robertson-More, Ted Wu

Surgical Endoscopy.2021; 35(6): 2428. CrossRef - Geospatial dynamics of COVID‐19 clusters and hotspots in Bangladesh

Ariful Islam, Md. Abu Sayeed, Md. Kaisar Rahman, Jinnat Ferdous, Shariful Islam, Mohammad Mahmudul Hassan

Transboundary and Emerging Diseases.2021; 68(6): 3643. CrossRef - Factors associated with the spatial heterogeneity of the first wave of COVID-19 in France: a nationwide geo-epidemiological study

Jean Gaudart, Jordi Landier, Laetitia Huiart, Eva Legendre, Laurent Lehot, Marc Karim Bendiane, Laurent Chiche, Aliette Petitjean, Emilie Mosnier, Fati Kirakoya-Samadoulougou, Jacques Demongeot, Renaud Piarroux, Stanislas Rebaudet

The Lancet Public Health.2021; 6(4): e222. CrossRef - A preliminary exploration of attitudes about COVID-19 among a group of older people in Iwate Prefecture, Japan

Lauren He, John W. Traphagan

Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology.2021; 36(1): 1. CrossRef - Unexpected high frequency of early mortality in COVID‐19: a single‐centre experience during the first wave of the pandemic

Diana Consuegra, Yoshua Seidner‐Isaacs, Didier Larios‐Sanjuan, Julieth Ibarra, Pedro Benavides‐Rodríguez, Samir Viloria, Emiro Buendía, Diego Viasus

Internal Medicine Journal.2021; 51(1): 102. CrossRef - “The Tragedy of the Commons”: How Individualism and Collectivism Affected the Spread of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Yossi Maaravi, Aharon Levy, Tamar Gur, Dan Confino, Sandra Segal

Frontiers in Public Health.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Sensitivity analysis of the infection transmissibility in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic

Pardis Biglarbeigi, Kok Yew Ng, Dewar Finlay, Raymond Bond, Min Jing, James McLaughlin

PeerJ.2021; 9: e10992. CrossRef - Contributions of human ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in determining host–pathogen interaction of COVID-19

SABYASACHI SENAPATI, PRATIBHA BANERJEE, SANDILYA BHAGAVATULA, PREM PRAKASH KUSHWAHA, SHASHANK KUMAR

Journal of Genetics.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Receiving Organ Support Therapies: The International Viral Infection and Respiratory Illness Universal Study Registry

Juan Pablo Domecq, Amos Lal, Christopher R. Sheldrick, Vishakha K. Kumar, Karen Boman, Scott Bolesta, Vikas Bansal, Michael O. Harhay, Michael A. Garcia, Margit Kaufman, Valerie Danesh, Sreekanth Cheruku, Valerie M. Banner-Goodspeed, Harry L. Anderson, Pa

Critical Care Medicine.2021; 49(3): 437. CrossRef - The link between vitamin D deficiency and COVID-19

DevasahayamJesudas Christopher, BarneyTJ Isaac, Balamugesh Thangakunam

Lung India.2021; 38(7): 4. CrossRef - Finding the real COVID-19 case-fatality rates for SAARC countries

Md Rafil Tazir Shah, Tanvir Ahammed, Aniqua Anjum, Anisa Ahmed Chowdhury, Afroza Jannat Suchana

Biosafety and Health.2021; 3(3): 164. CrossRef - Estimation of novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) reproduction number and case fatality rate: A systematic review and meta‐analysis

Tanvir Ahammed, Aniqua Anjum, Mohammad Meshbahur Rahman, Najmul Haider, Richard Kock, Md Jamal Uddin

Health Science Reports.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - COVID-SCORE Spain: public perceptions of key government COVID-19 control measures

Trenton M White, Lucinda Cash-Gibson, Jose M Martin-Moreno, Rafael Matesanz, Javier Crespo, Jose L Alfonso-Sanchez, Sonia Villapol, Ayman El-Mohandes, Jeffrey V Lazarus

European Journal of Public Health.2021; 31(5): 1095. CrossRef - How COVID-19 case fatality rates have shaped perceptions and travel intention?

Raymond Rastegar, Siamak Seyfi, S. Mostafa Rasoolimanesh

Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management.2021; 47: 353. CrossRef - Lockdown strategy worth lives: The SEIRD modelling in COVID-19 outbreak in Indonesia

I Nurlaila, A A Hidayat, B Pardamean

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Sci.2021; 729(1): 012002. CrossRef - Genomic Surveillance of Circulating SARS-CoV-2 in South East Italy: A One-Year Retrospective Genetic Study

Loredana Capozzi, Angelica Bianco, Laura Del Sambro, Domenico Simone, Antonio Lippolis, Maria Notarnicola, Graziano Pesole, Lorenzo Pace, Domenico Galante, Antonio Parisi

Viruses.2021; 13(5): 731. CrossRef - Dynamics of COVID-19 spreading model with social media public health awareness diffusion over multiplex networks: Analysis and control

Padmavathi Ramamoorthi, Senthilkumar Muthukrishnan

International Journal of Modern Physics C.2021; 32(05): 2150060. CrossRef - The relationship between measures of individualism and collectivism and the impact of COVID-19 across nations

Ravi Philip Rajkumar

Public Health in Practice.2021; 2: 100143. CrossRef - Facilities for Centralized Isolation and Quarantine for the Observation and Treatment of Patients with COVID-19

Xianliang Wang, Jiao Wang, Jin Shen, John S. Ji, Lijun Pan, Hang Liu, Kangfeng Zhao, Li Li, Bo Ying, Lin Fan, Liubo Zhang, Lin Wang, Xiaoming Shi

Engineering.2021; 7(7): 908. CrossRef - SARS-CoV-2 simulations go exascale to predict dramatic spike opening and cryptic pockets across the proteome

Maxwell I. Zimmerman, Justin R. Porter, Michael D. Ward, Sukrit Singh, Neha Vithani, Artur Meller, Upasana L. Mallimadugula, Catherine E. Kuhn, Jonathan H. Borowsky, Rafal P. Wiewiora, Matthew F. D. Hurley, Aoife M. Harbison, Carl A. Fogarty, Joseph E. Co

Nature Chemistry.2021; 13(7): 651. CrossRef - Recent advances in detection technologies for COVID-19

Tingting Han, Hailin Cong, Youqing Shen, Bing Yu

Talanta.2021; 233: 122609. CrossRef - Nanomedicine: A Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approach to COVID-19

Arjun Sharma, Konstantinos Kontodimas, Markus Bosmann

Frontiers in Medicine.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - A cross-sectional pilot study on COVID-19 disease pattern, recovery status and effect of co-morbidities in Bangladesh

Monirul Islam Md., Shahriar Saimon, Jannat Koly Fahima, Kabir Shaila, Asad Choudhury Abu, Ahmed Chowdhury Jakir, Rafat Tahsin Md., Shah Amran Md.

African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology.2021; 15(5): 84. CrossRef - Micronutrient zinc roles in adjunctive therapy for COVID-19 by enhancing patients immunoregulation and tolerance to the pathogen

Ba Xuan Hoang, Bo Han

Reviews in Medical Microbiology.2021; 32(3): 149. CrossRef - Dissecting the common and compartment-specific features of COVID-19 severity in the lung and periphery with single-cell resolution

Kalon J. Overholt, Jonathan R. Krog, Ivan Zanoni, Bryan D. Bryson

iScience.2021; 24(7): 102738. CrossRef - Psychological reaction to Covid-19 of Italian patients with IBD

Mariarosaria Savarese, Greta Castellini, Salvatore Leone, Enrica Previtali, Alessandro Armuzzi, Guendalina Graffigna

BMC Psychology.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Emerging mutation in SARS-CoV-2 spike: Widening distribution over time in different geographic areas

Ysrafil Ysrafil, Rosdiana Mus, Noviyanty Indjar Gama, Dwi Rahmaisyah, Riskah Nur'amalia

Biomedical Journal.2021; 44(5): 570. CrossRef - The impact of COVID-19 on rural population: A retrospective study

İbrahim Halil İNANÇ, Nurbanu BURSA, Ahmet GÜLTEPE, Cengiz ŞABANOĞLU

Journal of Health Sciences and Medicine.2021; 4(5): 722. CrossRef - Perceptions of primary healthcare physicians in Jordan of their role in the COVID‐19 pandemic: A cross‐sectional study

Rami Saadeh, Mahmoud A. Alfaqih, Amjad Al‐Shdaifat, Mohammad Alyahya, Nasr Alrabadi, Yousef Khader, Othman Beni Yonis, Mohammed Z. Allouh

International Journal of Clinical Practice.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Counting the Dead: COVID-19 and Mortality in Quebec and British Columbia During the First Wave

Yann Décarie, Pierre-Carl Michaud

Canadian Studies in Population.2021; 48(2-3): 139. CrossRef - Human Amniotic Fluid for the Treatment of Hospitalized, Symptomatic, and Laboratory-verified SARS-CoV-2 Patients

Mojgan Barati, Fakher Rahim

The Open Biology Journal.2021; 9(1): 36. CrossRef - The Drug Repurposing for COVID-19 Clinical Trials Provide Very Effective Therapeutic Combinations: Lessons Learned From Major Clinical Studies

Chiranjib Chakraborty, Ashish Ranjan Sharma, Manojit Bhattacharya, Govindasamy Agoramoorthy, Sang-Soo Lee

Frontiers in Pharmacology.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Epidemic size, trend and spatiotemporal mapping of SARS-CoV-2 using geographical information system in Alborz Province, Iran

Kourosh Kabir, Ali Taherinia, Davoud Ashourloo, Ahmad Khosravi, Hossien Karim, Hamid Salehi Shahrabi, Mojtaba Hedayat Yaghoobi, Alireza Soleimani, Zaynab Siami, Mohammad Noorisepehr, Ramin Tajbakhsh, Mohammad Reza Maghsoudi, Mehran Lak, Parham Mardi, Behn

BMC Infectious Diseases.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Micro-environmental conditions and high population density affects the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus-2 in metropolitan cities of India

Sanjay Dwivedi, Seema Mishra, Ruchi Agnihotri, Vishnu Kumar, Pragya Sharma, Geetgovind Sinam, Vivek Pandey

Environmental Disease.2021; 6(4): 116. CrossRef - Underlying Chronic Disease and COVID-19 Infection: A State-of-the-Art Review

Habib Haybar, Khalil Kazemnia, Fakher Rahim

Jundishapur Journal of Chronic Disease Care.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Twitter Sentiment Analysis during COVID19 Outbreak

Akash Dutt Dubey

SSRN Electronic Journal .2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Challenges in maintaining treatment services for people who use drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic

Adrian Dunlop, Buddhima Lokuge, Debbie Masters, Marcia Sequeira, Peter Saul, Grace Dunlop, John Ryan, Michelle Hall, Nadine Ezard, Paul Haber, Nicholas Lintzeris, Lisa Maher

Harm Reduction Journal.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Estimating Case Fatality Rate of Symptomatic Patients with COVID-19: Is This the Right Thing to Do?

Morteza Abdullatif Khafaie, Fakher Rahim

SSRN Electronic Journal .2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Three novel prevention, diagnostic, and treatment options for COVID-19 urgently necessitating controlled randomized trials

Richard I. Horowitz, Phyllis R. Freeman

Medical Hypotheses.2020; 143: 109851. CrossRef - Considerations for an Individual-Level Population Notification System for Pandemic Response: A Review and Prototype

Mohammad Nazmus Sakib, Zahid A Butt, Plinio Pelegrini Morita, Mark Oremus, Geoffrey T Fong, Peter A Hall

Journal of Medical Internet Research.2020; 22(6): e19930. CrossRef - Pandemia COVID-19, la nueva emergencia sanitaria de preocupación internacional: una revisión

R. Mojica-Crespo, M.M. Morales-Crespo

Medicina de Familia. SEMERGEN.2020; 46: 65. CrossRef - COVID-19 in the radiology department: What radiographers need to know

N. Stogiannos, D. Fotopoulos, N. Woznitza, C. Malamateniou

Radiography.2020; 26(3): 254. CrossRef - Promoting Physical Activity During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Obesity and Chronic Disease Management

Geoffrey M. Hudson, Kyle Sprow

Journal of Physical Activity and Health.2020; 17(7): 685. CrossRef - The DOSMD challenge and the COVID-19 conundrum

Ravi Philip Rajkumar

Schizophrenia Research.2020; 222: 475. CrossRef - Considerations for safety in the use of systemic medications for psoriasis and atopic dermatitis during theCOVID‐19 pandemic

Jose W. Ricardo, Shari R. Lipner

Dermatologic Therapy.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Tocilizumab for treatment of patients with severe COVID–19: A retrospective cohort study

Tariq Kewan, Fahrettin Covut, Mohammed J. Al–Jaghbeer, Lori Rose, K.V. Gopalakrishna, Bassel Akbik

eClinicalMedicine.2020; 24: 100418. CrossRef - Environmental concern regarding the effect of humidity and temperature on 2019-nCoV survival: fact or fiction

Narges Nazari Harmooshi, Kiarash Shirbandi, Fakher Rahim

Environmental Science and Pollution Research.2020; 27(29): 36027. CrossRef - Protocol of a population-based prospective COVID-19 cohort study Munich, Germany (KoCo19)

Katja Radon, Elmar Saathoff, Michael Pritsch, Jessica Michelle Guggenbühl Noller, Inge Kroidl, Laura Olbrich, Verena Thiel, Max Diefenbach, Friedrich Riess, Felix Forster, Fabian Theis, Andreas Wieser, Michael Hoelscher, Abhishek Bakuli, Judith Eckstein,

BMC Public Health.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - COVID-19 PANDEMİSİ DÖNEMİNDE ÜLKELERİN COVID-19, SAĞLIK VE FİNANSAL GÖSTERGELER BAĞLAMINDA SINIFLANDIRILMASI: HİYERARŞİK KÜMELEME ANALİZİ

Bilgehan TEKİN

Finans Ekonomi ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi.2020; 5(2): 336. CrossRef - Epidemiological characteristics of the COVID-19 outbreak in a secondary hospital in Spain

Christine Giesen, Laura Diez-Izquierdo, Carmen María Saa-Requejo, Inmaculada Lopez-Carrillo, Carmen Alejandra Lopez-Vilela, Alicia Seco-Martinez, María Teresa Ramirez Prieto, Eduardo Malmierca, Cristina Garcia-Fernandez

American Journal of Infection Control.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Accounting for Underreporting in Mathematical Modeling of Transmission and Control of COVID-19 in Iran

Meead Saberi, Homayoun Hamedmoghadam, Kaveh Madani, Helen M. Dolk, Andrei S. Morgan, Joan K. Morris, Kaveh Khoshnood, Babak Khoshnood

Frontiers in Physics.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Reflecting on the safety zoo: Developing an integrated pandemics barrier model using early lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic

Paul Lindhout, Genserik Reniers

Safety Science.2020; 130: 104907. CrossRef - Novel SARS-CoV-2 outbreak and COVID19 disease; a systemic review on the global pandemic

Abdulmohsen H. Al-Rohaimi, Faisal Al Otaibi

Genes & Diseases.2020; 7(4): 491. CrossRef - Sequential battery of COVID-19 testing to maximize negative predictive value before surgeries

NEERAJ SINHA, GALIT BALAYLA

Revista do Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - How a Barcelona Post-Acute Facility became a Referral Center for Comprehensive Management of Subacute Patients With COVID-19

Marco Inzitari, Cristina Udina, Oscar Len, Joan Ars, Cristina Arnal, Hugo Badani, Vanessa Davey, Ester Risco, Pere Ayats, Ana M. de Andrés, Cristina Mayordomo, Francisco J. Ros, Alessandro Morandi, Matteo Cesari

Journal of the American Medical Directors Associat.2020; 21(7): 954. CrossRef - Prior infection with intestinal coronaviruses moderates symptom severity and mortality in patients with COVID-19: A hypothesis and preliminary evidence

Ravi Philip Rajkumar

Medical Hypotheses.2020; 143: 110116. CrossRef - Spread of variants with gene N hot spot mutations in russian SARS-CoV-2 isolates

SA Kiryanov, TA Levina, MYu Kirillov

Bulletin of Russian State Medical University.2020; (2020(4)): 21. CrossRef - The COVID-19 pandemic: diverse contexts; different epidemics—how and why?

Wim Van Damme, Ritwik Dahake, Alexandre Delamou, Brecht Ingelbeen, Edwin Wouters, Guido Vanham, Remco van de Pas, Jean-Paul Dossou, Por Ir, Seye Abimbola, Stefaan Van der Borght, Devadasan Narayanan, Gerald Bloom, Ian Van Engelgem, Mohamed Ali Ag Ahmed, J

BMJ Global Health.2020; 5(7): e003098. CrossRef - The COVID-19 Pandemic: Diverse Contexts; Different Epidemics—How and Why?

Wim Van Damme, Ritwik Dahake, Alexandre Délamou, Brecht Ingelbeen, Edwin Wouters, Guido Vanham, Remco van de Pas, Jean-Paul Dossou, Por Ir, Seye Abimbola, Stefaan Van der Borght, Narayanan Devadasan, Gerald Bloom, Ian Van Engelgem, Mohamed Ali Ag Ahmed, J

SSRN Electronic Journal .2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Promising effects of tocilizumab in COVID-19: A non-controlled, prospective clinical trial

Farzaneh Dastan, Ali Saffaei, Sara Haseli, Majid Marjani, Afshin Moniri, Zahra Abtahian, Atefeh Abedini, Arda Kiani, Sharareh Seifi, Hamidreza Jammati, Seyed Mohammad Reza Hashemian, Mihan Pourabdollah Toutkaboni, Alireza Eslaminejad, Jalal Heshmatnia, Mo

International Immunopharmacology.2020; 88: 106869. CrossRef - Obese communities among the best predictors of COVID-19-related deaths

Antoine Fakhry AbdelMassih, Ramy Ghaly, Abeer Amin, Amr Gaballah, Aya Kamel, Bassant Heikal, Esraa Menshawey, Habiba-Allah Ismail, Hend Hesham, Josephine Attallah, Kirollos Eshak, Mai Moursi, Mariam Khaled-Ibn-ElWalid, Marwa Tawfik, Mario Tarek, Mayan Moh

Cardiovascular Endocrinology & Metabolism.2020; 9(3): 102. CrossRef - A Japanese case of COVID‐19: An autopsy report

Koji Okudela, Hiroyuki Hayashi, Yukihiro Yoshimura, Hiroaki Sasaki, Hiroshi Horiuchi, Nobuyuki Miyata, Natsuo Tachikawa, Yuki Tsuchiya, Hideaki Mitsui, Kenichi Ohashi

Pathology International.2020; 70(10): 820. CrossRef - Innate Immune Responses to Highly Pathogenic Coronaviruses and Other Significant Respiratory Viral Infections

Hanaa Ahmed-Hassan, Brianna Sisson, Rajni Kant Shukla, Yasasvi Wijewantha, Nicholas T. Funderburg, Zihai Li, Don Hayes, Thorsten Demberg, Namal P. M. Liyanage

Frontiers in Immunology.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Assessment of Epidemiological Determinants of COVID-19 Pandemic Related to Social and Economic Factors Globally

Mohammad Mahmudul Hassan, Md. Abul Kalam, Shahanaj Shano, Md. Raihan Khan Nayem, Md. Kaisar Rahman, Shahneaz Ali Khan, Ariful Islam

Journal of Risk and Financial Management.2020; 13(9): 194. CrossRef - Pathophysiology and treatment strategies for COVID-19

Manoj Kumar, Souhaila Al Khodor

Journal of Translational Medicine.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Laboratory biosafety measures involving SARS-CoV-2 and the classification as a Risk Group 3 biological agent

Alexa M. Kaufer, Torsten Theis, Katherine A. Lau, Joanna L. Gray, William D. Rawlinson

Pathology.2020; 52(7): 790. CrossRef - Molecular epidemiology of the first wave of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in Thailand in 2020

Jiratchaya Puenpa, Kamol Suwannakarn, Jira Chansaenroj, Pornjarim Nilyanimit, Ritthideach Yorsaeng, Chompoonut Auphimai, Rungrueng Kitphati, Anek Mungaomklang, Amornmas Kongklieng, Chintana Chirathaworn, Nasamon Wanlapakorn, Yong Poovorawan

Scientific Reports.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Can climatic factors explain the differences in COVID-19 incidence and severity across the Spanish regions?: An ecological study

Pedro Muñoz Cacho, José L. Hernández, Marcos López-Hoyos, Víctor M. Martínez-Taboada

Environmental Health.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - A comprehensive review about SARS-CoV-2

SK Manirul Haque, Omar Ashwaq, Abdulla Sarief, Abdul Kalam Azad John Mohamed

Future Virology.2020; 15(9): 625. CrossRef - Harnessing Recent Advances in Synthetic DNA and Electroporation Technologies for Rapid Vaccine Development Against COVID-19 and Other Emerging Infectious Diseases

Ziyang Xu, Ami Patel, Nicholas J. Tursi, Xizhou Zhu, Kar Muthumani, Daniel W. Kulp, David B. Weiner

Frontiers in Medical Technology.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Laboratory Findings, Comorbidities, and Clinical Outcomes Comparing Medical Staff versus the General Population

Mina Ebrahimi, Amal Saki Malehi, Fakher Rahim

Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives.2020; 11(5): 269. CrossRef - The Relationship Between Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Health-Related Parameters and the Impact of COVID-19 on 24 Regions in India: Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study

Ravi Philip Rajkumar

JMIR Public Health and Surveillance.2020; 6(4): e23083. CrossRef - Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Modeling Study of Factors Driving Variation in Case Fatality Rate by Country

Jennifer Pan, Joseph Marie St. Pierre, Trevor A. Pickering, Natalie L. Demirjian, Brandon K.K. Fields, Bhushan Desai, Ali Gholamrezanezhad

International Journal of Environmental Research an.2020; 17(21): 8189. CrossRef - Investigating duration and intensity of Covid-19 social-distancing strategies

C. Neuwirth, C. Gruber, T. Murphy

Scientific Reports.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Survival and Estimation of Direct Medical Costs of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Anas Khan, Yazed AlRuthia, Bander Balkhi, Sultan Alghadeer, Mohamad-Hani Temsah, Saqer Althunayyan, Yousef Alsofayan

International Journal of Environmental Research an.2020; 17(20): 7458. CrossRef - Time dynamics of COVID-19

Cody Carroll, Satarupa Bhattacharjee, Yaqing Chen, Paromita Dubey, Jianing Fan, Álvaro Gajardo, Xiner Zhou, Hans-Georg Müller, Jane-Ling Wang

Scientific Reports.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - https://www.crossref.org/webDeposit/

Betsy Varghese, Siba Shajahan, Harikrishnan Anilkumar, Retheesh K. Haridasan, Arya Rahul, Hariprasad Thazhathedath, Anish T. Surendran Nair

Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Science.2020; 9(46): 3411. CrossRef - COVID-19: Spatial analysis of hospital case-fatality rate in France

Marc Souris, Jean-Paul Gonzalez, Muhammad Adrish

PLOS ONE.2020; 15(12): e0243606. CrossRef - Investigating the Determinants of High Case-Fatality Rate for Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Italy

Francesco Barone-Adesi, Luca Ragazzoni, Maurizio Schmid

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness.2020; 14(4): e1. CrossRef - Riesgos, contaminación y prevención frente al COVID-19 en el quehacer odontológico: una revisión

Paul Martin Herrera-Plasencia, Erika Raquel Enoki-Miñano, Miguel Angel Ruiz-Barrueto

Revista de Salud Pública.2020; 22(5): 1. CrossRef - Environmental Concern Regarding the Effect of Humidity and Temperature on SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19) Survival: Fact or Fiction

Narges Nazari Harmooshi, Kiarash Shirbandi, Fakher Rahim

SSRN Electronic Journal .2020;[Epub] CrossRef - COVID-19 Infection in Medical Staffs versus Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Laboratory Findings, Comorbidities, and Clinical Outcome

Mina Ebrahimi, Amal Saki Malehi, Fakher Rahim

SSRN Electronic Journal .2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Infectious diseases epidemiology, quantitative methodology, and clinical research in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic: Perspective from a European country

Geert Molenberghs, Marc Buyse, Steven Abrams, Niel Hens, Philippe Beutels, Christel Faes, Geert Verbeke, Pierre Van Damme, Herman Goossens, Thomas Neyens, Sereina Herzog, Heidi Theeten, Koen Pepermans, Ariel Alonso Abad, Ingrid Van Keilegom, Niko Speybroe

Contemporary Clinical Trials.2020; 99: 106189. CrossRef - Elective Surgery during SARS-Cov-2/COVID-19 Pandemic: Safety Protocols with Literature Review

Lázaro Cárdenas-Camarena, Jorge Enrique Bayter-Marin, Héctor Durán, Alfredo Hoyos, César Octavio López-Romero, José Antonio Robles-Cervantes, Ernesto Eduardo Echeagaray-Guerrero

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery - Global Open.2020; 8(6): e2973. CrossRef

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite