Points to consider when developing drugs for dry eye syndrome

Article information

Abstract

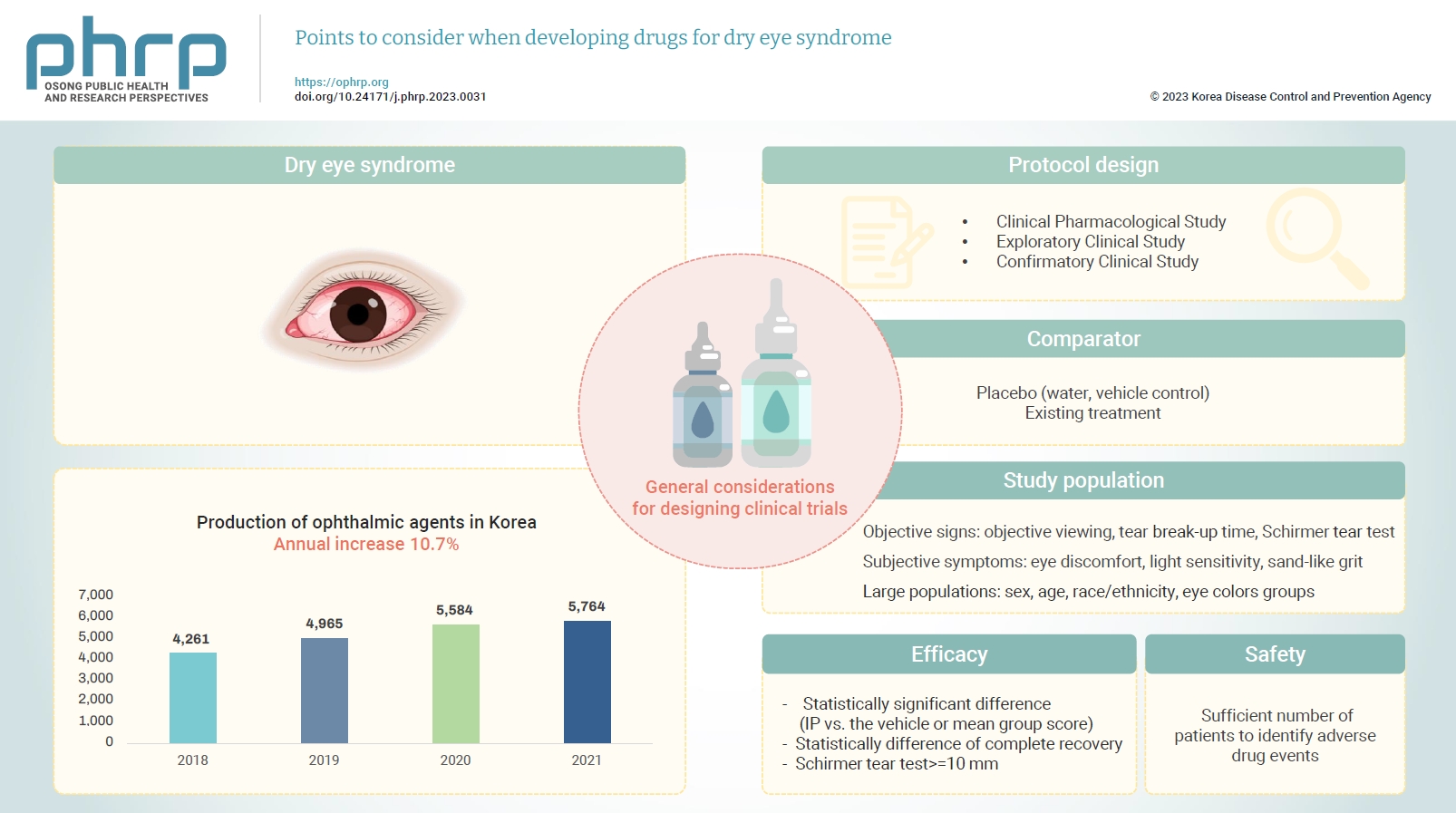

Changes in both the social environment (e.g., the increased use of electronic media) and the atmospheric environment (e.g., air pollution and dust) have contributed to an increasing incidence of eye disease and an increased need for eye care. Notably, the signs and symptoms of dry eye syndrome can impact the daily quality of life for various age groups, including the elderly, and usually requires active treatment. The symptoms of dry eye syndrome include tear film instability, hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities. As treatments for dry eye are being developed, a standardized guideline is needed to increase the efficiency of drug development and improve the quality of clinical trial data. In this paper, we present general considerations for the pharmaceutical industry and clinical trial investigators designing clinical trials focused on the development of drugs to treat dry eye syndrome.

Introduction

Eye diseases have been increasing in all age groups due to recent changes in the social environment such as the increased use of electronic devices (e.g., computers and cellular phones). In addition, the worsening air environment including fine particulates (e.g., dust) contributes to increases in eye disease. The need for eye care has increased because of these 2 factors. According to the Korea Pharmaceutical and Bio-Pharma Manufacturers Association, the production of ophthalmic agents (eye drops, eye ointments) has increased by approximately 10% every year over the past 3 years [1,2]. The domestic production of ophthalmic agents from 2018 to 2021 is presented in Table 1 [1,2]. In October 2020, the National Health Insurance Service took measures to reduce the price of ophthalmic agents because of the rapid increase in prescriptions for disposable eye drops [3] and because the marketing and usage of eye drops are expected to remain high.

Ophthalmic solutions are preparations administered to the eye, including liquid aseptic preparations applied to eye tissues such as the conjunctival sacs and solid aseptic preparations used in dissolution or suspension form. These preparations are usually made by adding excipients to the active ingredient and dissolving or suspending them in a solvent or by filling a container with excipients and the active ingredient to create a solid aseptic preparation [4]. Ophthalmic solutions include antihistamine-containing eye drops, used to alleviate symptoms such as allergic conjunctivitis, and artificial tears, used to alleviate dry eye symptoms.

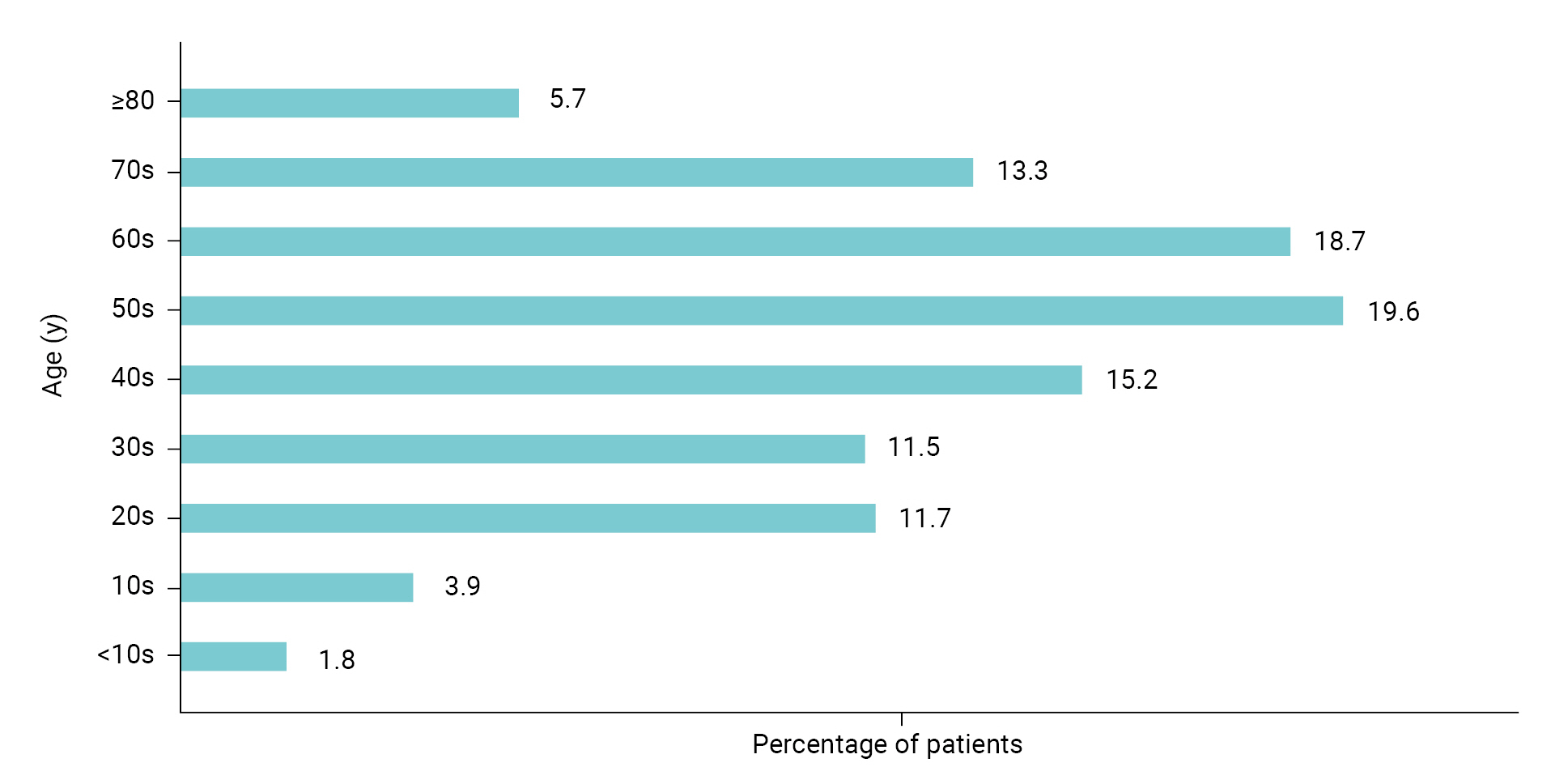

Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis in the tear film, resulting in tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities [5]. The eyes become sore and sensitive, with a feeling of foreign matter like grains of sand in the eye, which can lead to shooting pain and dryness. In severe cases, patients may complain of headaches, the eyes may be bloodshot, or the surface of the eye can be damaged. If it is clear that the dry eye symptoms are caused by disease, treatment of the disease improves it. Otherwise, the most common treatment is an “artificial tears” eye drop [6–9]. The signs and symptoms of dry eye syndrome are not only inconvenient but can also lower the quality of life for all age groups. As shown in Figure 1, the age groups affected by dry eye are evenly distributed from teenagers to adults in their 70s [10]. Active treatment is usually needed.

Since new treatments for dry eye continue to be developed, a standardized guideline is needed to support the efficiency of dry eye drug development and improve the quality of clinical trial data. The National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation (NIFDS) in the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety has published a relevant guideline [11]. Therefore, we suggest the general consideration when designing clinical trials, specifically for the pharmaceutical industry and clinical trial investigators who want to develop drugs for dry eye syndrome.

General Considerations for Clinical Trials

To conduct a clinical trial for the development of drugs to treat dry eye syndrome, the investigator should prepare a clinical trial protocol and submit the appropriate dossier according to the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act, Article 34 [12], the Regulation on Safety of Pharmaceuticals, etc, Article 24 [13], and the Regulation on Approval for Investigational New Drug Application of Drug [14]. Approval must be obtained from the Minister of Food and Drug Safety.

The design of clinical trials to develop dry eye syndrome drugs should follow the NIFDS general guidelines for clinical trials. However, special consideration must be given to the selection of the comparator, the target population, efficacy, safety, and clinical evaluation parameters.

Clinical Pharmacological Study

A clinical pharmacological study is a first-in-human trial to administer an investigational product (IP). It is necessary to conduct a clinical trial in healthy adults who can confirm the safety/tolerability and pharmacokinetics (systemic exposure) of the IP during a stepwise dose increase in single and repeated administration. Reasonable evidence for selection of the initial clinical dose and the stepwise dose increases should be provided by referring to nonclinical study data.

When the IP is applied to the eye for the first time, monocular administration is recommended for the single and subsequent administrations. If 2 drops are required at a time, an appropriate interval should be set because the tissue characteristics of the eye limit the amount that can be held in the eye (approximately 20−30 μL). When performing pharmacokinetic analysis to confirm the degree of systemic exposure after administration, parent drug (unchanged substance) and active metabolite analyses should be performed, considering the characteristics of the IP. If the IP binds to red blood cells and requires whole blood analysis, both whole blood and plasma should be analyzed. It is necessary to establish the inclusion/exclusion criteria as they relate to ophthalmology, and a safety evaluation including an ophthalmological examination and local tolerability evaluation should be conducted by an ophthalmologist.

Exploratory Clinical Study

An exploratory clinical study is first conducted to explore the IP and determine the dosing, study design, evaluation items, and evaluation methods for the subsequent confirmatory clinical study. It is necessary to verify the appropriate concentration, administration method, and dose to confirm the validity of the indication results for patients with dry eye syndrome. In addition, a dose-response study is needed to assess the safety of the IP.

Confirmatory Clinical Study

A confirmatory clinical study is conducted to confirm the safety and efficacy of the IP. In general, it is recommended to verify the safety and efficacy under conditions involving traditional environmental exposures (e.g., seasonal). However, a challenge model study using a control chamber in which temperature, airflow, humidity, and other factors are controlled may also be considered. Add-on treatment in which the IP is added to a standardized treatment regimen is also acceptable.

Comparator

In a comparative clinical study for the development of drugs to treat dry eye syndrome, the comparator may be a placebo (i.e., a vehicle including excipients but excluding the active ingredient) or an existing treatment. It is recommended that the IP demonstrates statistical and clinical superiority over the comparator in a randomized, double-blind, and parallel-design trial. Therefore, since water is commonly used in drugs to treat dry eye syndrome and is known as an effective ingredient in itself, a vehicle control should be used as a comparator in the comparative clinical study. Since there are currently no known effective treatments for dry eye syndrome, equivalence or non-inferiority trials are not recommended without good analytical validation (sensitivity) methods (including both positive and negative controls).

Study Population

Patients with eye discomfort consistent with dry eye syndrome should be enrolled. The inclusion criteria should include both objective signs and subjective symptoms. The signs of dry eye are determined by objective viewing of the eye surface through corneal staining, conjunctival staining, measuring tear break-up time, and Schirmer tear test scoring, and others. The symptoms of dry eye are subjective experiences of eye discomfort, such as blurred vision, light sensitivity, a feeling of sand-like grit in the eye, and others. It is important that studies include large populations with demographic subgroups, including different sex, age, race/ethnicity, and eye color groups.

Dry eye secondary to scarring (e.g., from irradiation, alkali burns, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, cicatricial pemphigoid) or the destruction of conjunctival goblet cells (as with vitamin A deficiency) are considered severe and patients with these conditions should be studied separately from routine dry eye syndrome. Severe blepharitis or obvious inflammation at the eyelid margin can interfere with the interpretation of study results, and patients with these conditions should also be studied separately from routine dry eye syndrome.

In studies aimed at developing drugs to treat dry eye syndrome, exclusion criteria for the study population should be established, considering criteria such as vision parameters, ophthalmic diseases, surgical history, prior medications/concomitant drugs, and history of wearing contact lenses.

Recommended exclusions: (1) a maximum corrected vision; (2) ophthalmic diseases, such as ocular hypertension, glaucoma, allergy, active eye inflammation (uveitis, iritis, blepharitis, etc), autoimmune disease (Sjögren’s syndrome, etc), retinal disease, and other clinically significant eye diseases that are not caused by dry eye syndrome (e.g., corneal surface disease, abnormal corneal sensitivity, excessive secretion of tears, etc); (3) ophthalmic surgery such as vision correction surgery (refractive correction such as LASIK, etc), or cataract surgery where a sufficient recovery period has not elapsed since punctal occlusion, etc; (4) current drugs that may affect the evaluation of safety and efficacy: (a) preparations for dry eye syndrome (e.g., eye drops, anti-inflammatory drugs such as cyclosporin, hyaluronic acid preparations, tetracycline preparations); (b) preparations known to cause dry eye syndrome or drugs that may affect the evaluation of safety and efficacy (e.g., oral contraceptives, anticholinergic drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, hypnotics, diuretics, antimuscarinic drugs, β-blockers, oral aspirin, corticosteroids, mast cell stabilizers); and (5) if contact lenses have been worn recently or contact lenses are required during clinical trials.

Efficacy

In general, safety and efficacy should be demonstrated in appropriate and well-controlled multicenter studies. Dry eye syndrome is a disease sensitive to the surrounding environment, and it can be difficult to objectively prove the efficacy of drugs through the subjective reaction of patients. It is recommended that efficacy be demonstrated in a natural exposure study with repeated administrations over a sufficient period of time, considering the mechanism of action of the IP and the purpose of treatment. It is recommended that one of the following are demonstrated: (1) a statistically significant difference between the IP and the vehicle for at least 1 objective predefined sign of dry eye (mean group score of the IP versus the vehicle) and at least 1 subjective predefined symptom of dry eye (mean group score); (2) a statistically significant difference between the percentage of patients who have reached complete recovery of corneal staining; or (3) a statistically significant difference between the percentage of patients who increased ≥10 mm in their Schirmer tear test scores.

If signs and symptoms are used to demonstrate efficacy, several different endpoints for the objective sign or the subjective symptom are recommended: (1) signs of dry eye include, but are not limited to corneal staining results, conjunctival staining results, decreased tear break-up time, and decreased Schirmer tear test scores (with or without anesthesia); (2) symptoms of dry eye include, but are not limited to, blurred vision, light sensitivity, a feeling of sand in the eye, ocular irritation, ocular pain or discomfort, and ocular itching.

Subjective symptom improvement can also be demonstrated by showing statistically significant differences in the percentage of patients who have reached complete recovery of symptoms. The regulatory agency should be consulted if cases are to be included where complete recovery (complete clearing of signs or symptoms) has not been achieved in the responder analysis. In other words, responders should be defined in advance.

Efficacy for a sign and efficacy for a symptom need not be demonstrated in the same clinical trial, but should be demonstrated in one or more clinical trials. The sponsor should describe all the scoring methods or scales used to measure the efficacy variables and submit the scoring methods or scales with the clinical trial protocol. The scoring methods or scales should be verified methods.

Pivotal clinical trials should be conducted using the formulation that is proposed for marketing. If only the efficacy for a sign is demonstrated in a pivotal clinical trial, the drug indications may be limited according to the results. Thus, the efficacy for a certain symptom should be confirmed based on a secondary endpoint.

Safety

The study should include a sufficient number of patients to identify adverse drug events. To achieve this, a sufficient number of patients using the IP should complete treatment with a concentration and frequency of use at least as high as is proposed for marketing.

Before submitting an application dossier for marketing authorization, it is necessary to ensure that follow-up observations were completed over a sufficient period following administration. Evaluations should be conducted over a sufficiently long period of time (e.g., 12 months) [15].

For reformulations of drug substances that have already been approved in the same dosage form, the same route of administration, and the same or lower concentration, a shorter period of treatment may be considered when safety information is included from a sufficient number of patients.

It is recommended to demonstrate safety in a natural exposure study using repeated administrations over a sufficient period of time. If the efficacy study period is shorter, it is recommended that the safety study be conducted for at least 6 weeks.

Other Considerations

Excipients may be certified in Korea and abroad and their purpose in the drug combination should be pharmaceutically reasonable. The excipient should have no direct pharmacological effect and should not decrease the efficacy of the drugs or interfere with quality control. If there is no previous experience with the excipient in Korea, data to confirm its safety (e.g., nonclinical data) are needed. For nonclinical study data, one should refer to the NIFDS guideline on the nonclinical evaluation of pharmaceuticals [16].

Conclusion

According to the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, the number of patients with dry eye in Korea was approximately 2.45 million in 2020 and the condition was evenly distributed across age groups (teenagers to older adults in their 70s) [10]. Most of the drugs to treat dry eye syndrome in domestic and foreign markets are dominated by products from global pharmaceutical companies. Most of the domestic market is also dominated by drugs that originated in the United States (US), Japan, and Switzerland. The global market for dry eye syndrome treatments was approximately 6.5 trillion won (5,465 million US dollars) in 2021 and is expected to grow at an annual rate of 4.8% from 2022 to 2027 [17]. The domestic market for drugs to treat dry eye syndrome reached 300 billion won in 2020 [18] and the market is expected to continue growing as the number of patients with dry eye increases every year. Furthermore, with the expiration of patents in 2021 for the current drugs used to treat dry eye syndrome, generic drugs have been released, and a number of domestic pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical companies have begun developing new drugs to treat dry eye syndrome, as well as launching the generic drugs.

A draft guideline for developing drugs to treat dry eye syndrome was published by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2020 [19], and has not yet been finalized. In Korea, a guideline has been published [11] to support the development of effective drugs to treat dry eye syndrome by increasing the efficiency of drug development and improving the quality of clinical trial data. We hope that this paper, based on the Korean guideline [11], will help the domestic pharmaceutical industry and investigators who want to design clinical trial protocols for developing drugs to treat dry eye syndrome.

HIGHLIGHTS

This paper offers general considerations for designing clinical trials to develop drugs that treat dry eye syndrome, including the protocol design, study population, comparator, and efficacy endpoints. This information is intended to help the pharmaceutical industry and clinical trial investigators.

Notes

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

None.

Availability of Data

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Other data may be requested through the corresponding author.

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: SB, HS, HJO; Writing–original draft: SB, HS; Writing–review & editing: HS, HJO. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.