Psychological outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic among pregnant women in Indonesia: a cross-sectional study

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to analyze the psychological outcomes of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in several areas that are epicenters for the spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in Indonesia.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used data obtained from an online survey administered to 120 women who were pregnant and gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. The psychological condition of pregnant women was measured using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 questionnaire which was modified for conditions experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. We classified pregnant women into 2 groups according to their psychological condition: pregnant women who experienced anxiety and pregnant women who did not experience anxiety or felt normal. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was undertaken for the 2 groups. This study also used univariate analysis and bivariate analysis.

Results

The results of the ROC analysis resulted in a cutoff score of 3.56. The proportion of respondents who felt anxious was 53.3% and the proportion of respondents who did not feel anxious or felt normal was 46.7%. Anxiety was most common among pregnant women with high education levels, gestational age <19 weeks, and working pregnant women.

Conclusion

Maternal health services need to be performed with strict health protocols, complemented by pregnancy counseling services. This will provide a feeling of comfort and safety as pregnant women receive health services and give birth.

Introduction

Since severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus first broke out in China in December 2019, it has continued to spread [1,2]. The resultant coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [3], which has had an extremely negative impact on public health [4]. The health care system faces numerous disruptions as the death toll from the virus continues to increase and becomes increasingly more difficult to control [5]. The COVID-19 pandemic has also taken a significant toll on the world economy [6]. Millions of people have experienced layoffs and poverty as a result of the pandemic [7,8], which has led to an increase in psychological disorders in some communities [9–11].

Mental health problems as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic also afflict pregnant women [12,13], which are one of the pandemic’s most vulnerable groups [14,15]. In addition to the risk of infection, pandemic conditions result in limited physical activity and a disruption of maternal health services which in turn affect the mental health of pregnant women [16,17]. Poor mental health in pregnant women poses risks for adverse birth outcomes, such as miscarriage, premature birth, complications during childbirth, and death [18,19].

Pregnant women need psychological support to carry out pregnancy and childbirth during the COVID-19 pandemic [20,21]. Maternal health services need to be implemented with strict health protocols so that pregnant women can obtain health services with a low risk of COVID-19 infection. These services must also be supplemented by pregnancy counseling services, which improve the mental health of pregnant women [22]. In addition, psychological support needs to be provided by the family, especially by their partners [23], which can provide a feeling of comfort for pregnant women [24].

However, these standards have been difficult to meet during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. The accessibility of safe maternal health services is still not optimal, especially in areas that are considered epicenters of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, such as Jakarta, where health services are more focused on treating COVID-19 patients. Thus, non-COVID-19 health services have faced many disruptions [25]. Many pregnant women struggle to access maternal health services at all, and if they do, they may encounter inadequate health protocols. This increases the risk of pregnant women becoming infected [26].

People have also faced economic pressure also during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many people have lost their jobs and income, including people in households with pregnant women. This further increases the mental health burden of pregnant women [27–29]. In addition, pregnant women who work also face severe psychological stress [30]. There is no extended leave policy for pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Even working hours are generally reduced, pregnant women do continue to work. Of course, working while pregnant during pandemic conditions is very difficult for pregnant women, many of whom experience mental health problems [31].

This study analyzed the psychological condition of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. The purpose of this study was to analyze the psychological outcomes of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic in several areas that have become epicenters for the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Indonesia. The results of this study are expected to help pregnant women overcome psychological health problems and help health workers provide maternal health services that can promote a feeling of security for pregnant women.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This cross-sectional study used data obtained from online surveys. An online survey was conducted to avoid face-to-face or physical data collection between researchers and respondents. Face-to-face or physical data collection would have a high risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission between researchers and respondents. In addition, Indonesian regulations also restrict public and social activities, including field research. As a result, we decided to use an online survey in this study to examine the psychological outcomes of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia.

Data and Study Sample

Data were collected online using an online questionnaire. The data collection period was carried out from October 19, 2020 to November 19, 2020. Questionnaires were distributed through the community networks of pregnant women, whose contact numbers were obtained from various sources, such as health personnel, lecturer networks, and community members. Questionnaires were also distributed through social media.

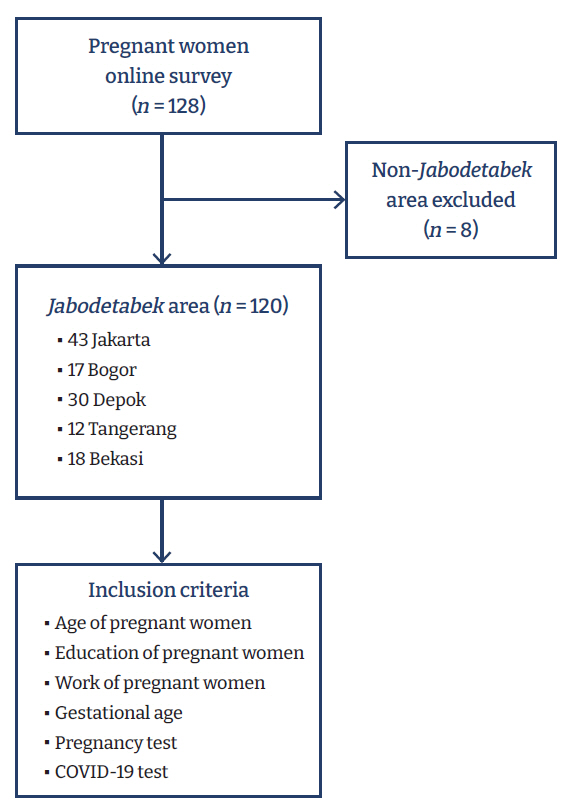

The samples in this study were women who were pregnant or gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 was declared to be a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020. The study locations were the epicenters for the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Indonesia, including Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi. These 5 regions are integrated with each other and considered 1 regional unit, referred to as the Jabodetabek area. The sample selection method is shown in Figure 1.

Method of Measurement and Analysis

We developed a new questionnaire to assess the psychological outcomes of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. This questionnaire was developed by referring to the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 questionnaire, in particular the anxiety component of the instrument [32]. We used 8 variables: (1) feeling unable to obtain maternal health services; (2) feeling unable to take care of household needs; (3) feeling worried about the condition of their pregnancy and the fetus; (4) feeling afraid of the childbirth process; (5) feeling worried about being unable to carry out physical activities, such as sports, during pregnancy; (6) feeling worried about not getting childbirth assistance from their partner; (7) feeling worried about the condition of social relationships; and (8) feeling worried about not being able to adapt to normal life during the pandemic. Each variable was measured using a Likert scale: 1 (very high), 2 (high), 3 (moderate), 4 (low), and 5 (very low).

We calculated the total value of the 8 variables and determined the average value to quantify the psychological outcome of each respondent. We then dichotomized these values using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, which is a visual representation of the relationship between sensitivity and specificity. The ROC curve is generated based on the calculation of a confusion matrix between the false-positive rate and the true-positive rate, which is used to divide data based on a cutoff point [33,34]. We calculated the cutoff point of the ROC curve, and a mean value less than or equal to the cutoff point was categorized as not anxious or normal, while a mean value greater than the cutoff point was categorized as anxious. We also used univariate and bivariate analysis in this research.

Ethical Considerations

This study received ethical permission from the Ethics Committee of the Veterans National Development University of Jakarta (No. 2789/X/2020/KEPK).

Results

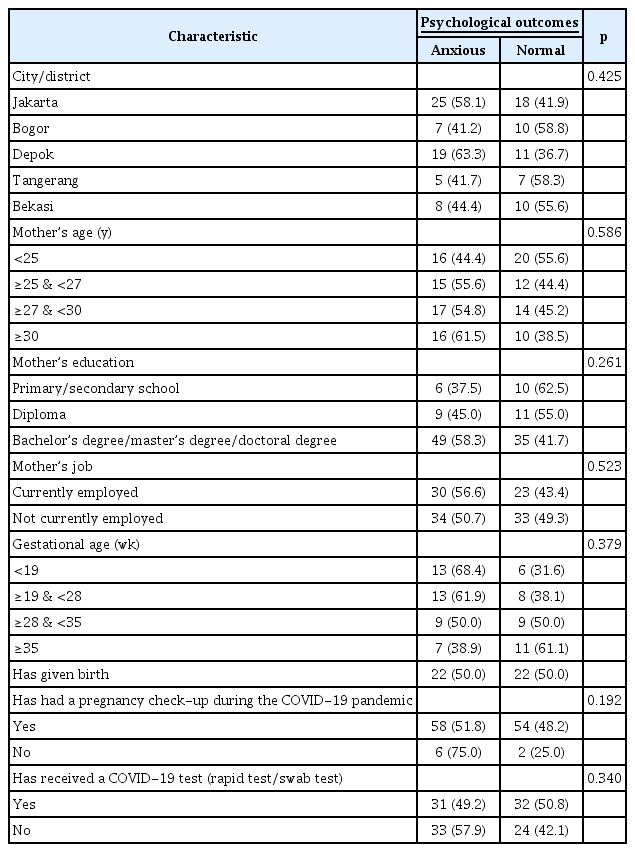

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. Univariate analysis showed that 35.8% of respondents lived in Jakarta, 14.2% in Bogor, 25.0% in Depok, 10.0% in Tangerang, and 15.0% in Bekasi. With regard to age, 30.0% of respondents were <25 years of age, 22.5% between ≥25 and <27 years old, 25.8% between ≥27 and <30 years old, and 21.7% ≥30 years old.

Most of the participants had relatively high education levels; specifically, 0.8% of respondents had only completed elementary school, 12.5% had completed up to high school, 16.7% had completed a bachelor’s degree, and 70.0% had completed their bachelor’s, master’s, or doctoral degrees. Slightly fewer than half (44.2%) of respondents worked, while 55.8% did not. The proportion of respondents whose gestational age was <19 weeks was 15.8%, while 17.5% had a gestational age from ≥19 to <28 weeks, 15.0% from ≥28 to <35 weeks, and 15.0% ≥35 weeks. The proportion of those who had given birth was 36.7%.

Fully 93.3% of respondents had received antenatal care, while 6.7% had never had a prenatal examination. The proportion of respondents who had been tested/tested for COVID-19 (rapid test/swab test) during pregnancy was 52.5%, while 47.5% had never been tested for COVID-19 (Table 1).

The ROC results had a cutoff point of 3.56. The average value was 3.54 and the standard deviation was 0.51. Based on the ROC analysis, the proportion of respondents who felt anxious was 53.3% and the proportion of respondents who did not feel anxious or felt normal was 46.7% (Table 2).

The results of the bivariate analysis showed that the highest concentration of respondents feeling anxious was in Depok, with 58.1% of respondents from this region reporting anxiety, while the lowest concentration was in Bogor, with only 41.2% reporting anxiety. The group with the largest proportion of respondents experiencing anxiety was respondents ≥30 years old, with a total of 61.5% reporting feeling anxious. The group with the lowest anxiety rate was respondents <25 years old, of whom only 44.4% reported feeling anxious.

Furthermore, respondents with a higher education level (bachelor degree/master’s degree/doctoral degree) had a higher anxiety rate (58.3%) than those with a secondary education or lower, of whom 37.5% reported feeling anxious. Working pregnant women were mostly in the anxious category as well, as 56.6% reported feeling anxious. Among pregnant women who did not work, 50.7% reported anxiety.

The lower the gestational age of the respondents, the greater the percentage of respondents who reported feeling anxious. The percentage of respondents with a gestational age <19 weeks who reported anxiety was 68.4%, whereas only 38.9% of respondents with a gestational age ≥35 weeks reported anxiety. However, for respondents who had given birth, the percentage of anxious respondents increased to 50.0%. Furthermore, respondents who had never had a prenatal check-up were more anxious, with 75.0% reporting anxiety. Meanwhile, only 51.8% of who had a prenatal check-up reported anxiety. Of respondents who had not been tested for COVID-19, 57.9% were in the anxious category, while only 49.2% of respondents who had been tested for COVID-19 reported feeling anxious (Table 3).

Discussion

The rapid spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the Jabodetabek area has disrupted maternal health services. Several maternal health facilities were closed to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2. The Indonesian government also limits physical activity (physical distancing) in public spaces to reduce the spread of the virus [35]. These measures have all had impacts on the psychological condition of pregnant women [12,13].

This study evaluated the psychological status of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic, many of whom reported feelings of anxiety, which can have a negative effect on the health condition of pregnant women and increase the risk of adverse birth outcomes [36–38]. Several findings of this study are noteworthy. First, the likelihood of experiencing psychological distress was higher in areas with a high rate of spread of the virus and fewer available health facilities, such as Depok. This can be explained by the greater likelihood of being infected with the virus in general, making it difficult to access maternal health services.

Education level also affected the psychological health of pregnant women. Mothers with higher education levels tended to have more feelings of anxiety than mothers with lower education levels. This may be because higher levels of awareness of the threat posed by the virus increase anxiety. However, precisely this knowledge should also allow a person to better adapt to pandemic conditions [39].

The rate of experiencing anxiety was also higher among pregnant women who worked, who have a higher risk of psychological distress than pregnant women who do not work [40]. This may be due to having to carry out work-related activities in pandemic conditions, in addition to experiencing pregnancy [41]. Moreover, pregnant women can experience emotional instability. These factors result in increased feelings of anxiety during pregnancy for women who work, for whom it is unsafe to perform work activities outside the home. As a result, it is encouraged for pregnant women who work and working women who recently gave birth to take time off work during the pandemic.

Pregnant women with a gestational age <19 weeks experience greater psychological problems than those with a gestational ≥19 weeks. Anxiety in early pregnancy occurs because pregnant women feel worried about not receiving high-quality maternal services during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the beginning of pregnancy, pregnant women want to make sure that their pregnancy is in good condition and that the fetus is healthy, so they need to receive a prenatal check-up. However, as a result of psychological distress, pregnant women may choose not to receive antenatal care at health facilities due to worries about being infected with SARS-CoV-2 [42].

Psychological distress is also caused in part by information regarding the high risk and effects of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant women. Pregnant women with COVID-19 can experience health problems such as acute respiratory infection, pneumonia, high fever, lymphocytopenia, and fatigue [43–45]. The clinical symptoms of COVID-19 may require intensive care for pregnant women with the virus [46]. COVID-19 can also have an effect on obstetric outcomes, such as premature births, the need for cesarean sections, a low birth weight, and neonatal death [47–49]. This information often causes anxiety in pregnant women.

The COVID-19 pandemic seriously disrupted the maternal health service system, especially at the onset of the pandemic. Health protocols in the maternal health service system were designed and implemented very slowly by the government, which resulted in low access to maternal health services for pregnant women [50]. The high risk level of infection for pregnant women and the disruption of access to maternal health services caused pregnant women to experience psychological problems during pregnancy [51]. Therefore, efforts to improve health protocols and maternal health services that are comfortable and safe are necessary for pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic [52].

In addition, the role of the family is very important for providing comfort to pregnant women during the pandemic. Comfort plays an important role in reducing the likelihood of psychological disorders in pregnant women [53,54]. This includes family members showing discipline in their application of health protocols during interactions with pregnant women.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused psychological problems for many pregnant women. Therefore, it is necessary to provide psychological guidance to reduce the likelihood of severe psychological disorders. Providers of maternal health services for pregnant women must also provide security and a sense of comfort for pregnant women by devising and adhering to strict health protocols. Likewise, family support is very important for the psychological condition of pregnant women. A government policy is also needed to provide a longer leave for working pregnant women and working women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Such a policy would allow working women to experience pregnancy and childbirth comfortably with fewer psychological problems.

Notes

Ethics Approval

This study received ethical permission from the Ethics Committee of the Veterans National Development University of Jakarta (No. 2789/X/2020/KEPK). Participants were given consent form prior to data collection and all data were completely anonymized after obtaining their permission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This study was funded by Research and Community Service Institution of Universitas Pembangunan Nasional (UPN) Veteran Jakarta, Indonesia.

Availability of Data

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. For other data, these may be requested through the corresponding author.

Additional Contributions

We are grateful to the Research and Community Service Institution of Universitas Pembangunan Nasional Veteran Jakarta, Indonesia; Department of Public Health, Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah, Jakarta, Indonesia; and Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic Indonesia for their institutional support throughout this study.