Epidemiological Characteristics of Field Tick-Borne Pathogens in Gwang-ju Metropolitan Area, South Korea, from 2014 to 2018

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

The importance of tick-borne diseases is increasing because of climate change, with a lack of long-term studies on tick-borne pathogens in South Korea. To understand the epidemiological characteristics of tick-borne diseases, the monthly distribution of field ticks throughout the year was studied in South Korea between May 2014 and April 2018 in a cross sectional study.

Methods

The presence of various tick-borne pathogens (Rickettsia species, Borrelia species, Anaplasma phagocytophilum) was confirmed by using polymerase chain reaction, to provide information for a prevention strategy against tick-borne pathogenic infections, through increased understanding of the relationship between seasonal variation and risk of infection with Rickettsia species. This was performed using logistic regression analysis (SPSS 20, IBM, USA) of the data obtained from the study.

Results

During the study period there were 11,717 ticks collected and 4 species identified. Haemapysalis longicornis was the most common species (n = 10,904, 93.1%), followed by Haemapysalis flava (n = 656, 5.6%), Ixodes nipponensis (n = 151, 1.3%), and Amblyomma testudinarium (n = 6, 0.05%) The results of this cross-sectional study showed that Haemapysalis flava carried a higher risk of transmission of Rickettsia species than other tick species (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

In conclusion, due attention should be paid to preventing tick-borne infections in humans whilst engaged in outdoor activities in Spring and Autumn, particularly in places where there is a high prevalence of ticks.

Introduction

Ticks are important vectors that can spread various pathogenic bacteria, viruses, and protozoans [1]. There are reports worldwide that ticks are responsible for causing various diseases, such as Rickettsioses, Borreliosis, Anaplasmosis, Ehrlichiosis. These diseases are often responsible for causing acute febrile illness in soldiers, and people exposed to ticks, either through their pets or by being in fields or wild areas [2]. There have been 5 genera of ticks, including 30 species, reported on the Korean peninsula and Japan [3]. Among them, Haemaphysalis longicornis, Haemaphysalis flava, and Ixodes nipponensis are the predominant species [4].

Rickettsia is an intracellular symbiotic bacterium, and Rickettsioses is globally known to manifest as an acute febrile illness in human [5]. About 30 species of Rickettsia were previously reported to be transmitted by ticks, of which 20 are known to be pathogenic [6]. In Korea, R. japonica (a pathogenic Rickettsia), was first isolated from a patient in 2006 [7]. Rickettsia species vary according to regions and arthropod vectors, for example R. rickettsii, R. pakeri, R. canadensis, and R. belli are present in America, R. slovaca, R. africae, R. raoultii and R. conorii are reported in Europe and Africa, R.sibirica, and R.japonica are found in Asia [8], R. massiliae is reported worldwide (except in Australia), and R. felis is reported all around the world [8]. Most species of Rickettsia are transmitted by ticks [8]. R. prowazekii is transmitted to humans by lice, and R. felis and R. typhi are transmitted by fleas [9], R. akari and R. felis are transmitted by Mesostigmatid mite. For the detection and classification of Rickettsia in species in specimens, the conserved 16S rRNA gene region was used. Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species are intracellular bacteria that infect leukocytes and are included in the family Anaplasmataceae. Anaplasma contains 6 species and Ehrlichia contains 10 species [10]. Gene sequencing analysis of the conserved 16S rRNA region is one of the key methods to categorize Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species [11]. Rickettsial pathogens (Rickettsia, Anaplasma, and Ehrlichia) are a public health threat in Korea [12], and are reported to be transmitted by ticks [13]. Borrelia afzelii, B. garinii, and B. burgdorferi are the major causative agents of Lyme borreliosis that has been reported in the northern hemisphere [14]. Borrelia species vary according to the host that transmits it [15]. Rodent ticks and bird ticks transmit B. afzelii and B. garinii, respectively [15]. Both rodents and birds can be the hosts for transmission of B. burgdorferi [15]. FlaB (Flagellin) proteins of Borrelia are conserved regions which are used for molecular diagnosis [16]. B. burgdorferi was first isolated from ticks in Korea in 1993 [17].

With increasing climate change there is a greater proliferation in the tick population, therefore the burden of various tick-borne diseases is also increasing [18]. Hence, it is necessary to understand the distribution patterns of ticks and the prevalence of tick-borne pathogens to take preventive measures. In this study, the pattern of distribution of various ticks was investigated each month for 4 years (May 2014 to April 2018), and a molecular study of various tick-borne pathogens was performed. Risk factors for transmission of Rickettsia species, were assessed and showed a high detection rate in field ticks in Gwang-ju Ju metropolitan area, South Korea.

Materials and Methods

1. Tick collection and sample preparation

For 4 years (May 2014-April 2018), field ticks were collected by the dragging/flagging method using 1 m × 1 m flannel over a 100 m2 rural area (N 35° 13′, E 126° 54′) monthly. The ticks were morphologically identified using Yamaguti’s keys [3].

2. DNA extraction

By species and stage of development, 1 to 3 adults, 10 to 30 larvae, and 30 to 50 nymphs were pooled (1 pool), and in 1.7 mL tubes with 700 μL of sterile phosphate-buffered solution, and 2 mm stainless steel beads and spun at 8,000 rpm for 20 seconds in a homogenizer (Precelly 2000, Bertin Technology, France). DNA extraction from the tick samples was performed by using a Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The genomic DNA was stored at 4°C until the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed.

3. Detection of Rickettsia-specific DNA

For Rickettsia detection, the 16S rRNA gene coding sequence was used [19]. The primer sequences of the 16S rRNA were: forward (16S-F), 5′-TAAGGAGGTAATCCAGCC-3′; and reverse (16S-R), 5′-CCTGGCTCAGAACGAA-3′. PCR was performed in an Applied Biosystems 9700 Thermal cycler (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, USA) as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 52°C for 1 minute, and elongation at 72°C for 2 minutes, using a Geneamp 9700 Biosystem (ABI, California). The amplification products (16S rRNA:1,482 bp) were analyzed after electrophoresis using a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

4. Detection of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia-specific DNA

For Anaplasma and Ehrlichia detection, a nested PCR was performed using the 16S rRNA gene coding sequence [10]. The primer sequences (AE1-F) of the first PCR were: forward, 5′-AAGCTTAACACATGCAAGTCGAA -3′; and reverse (AE1-R), 5′-AGTCACTGACCCAACCTTAAATG-3′. PCR was performed as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 minutes, annealing at 59°C for 1 minutes, and elongation at 72°C. The second PCR was performed with Anaplasma and Ehrlichia specific primer. The Anaplasma primers used were: forward (AP-F), 5′-AGTCACTGACCCAACCTTAAATG-3′; reverse (AP-R), 5′-GTCGAACGGATTATTCTTTATAGCTA-TAGCTTGC-3′. The Ehrlichia primers used were: forward (EC-F), 5′-CAATTGCTTATAACCTTTTGGTTAT-AAAT-3′; and reverse (EC-R), 5′-TATAGGTACCGTCATTATCTTCATTATCTTCCCTAT-3′. PCR was performed as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, annealing at 56°C for 1 minute, and elongation at 72°C for 2 minutes. The amplification products (Anaplasma, 926 bp; Ehrlichia: 390 bp) were analyzed after electrophoresis using a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

5. Detection of Borrelia-specific DNA

For Borrelia detection, the FlaB gene coding sequence was used [20]. The primer sequences of the FlaB protein for outer reaction were: forward (132f), 5′-TGGTATGGGAGTTTCTGG-3′; and reverse (905r), 5′-TCTGTCATTGTAGCATCTTT-3′. PCR was performed as follows: denaturation at 94 °C for 10 minutes, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 50°C for 45 seconds, and elongation at 72°C for 1 minute. The primer sequences of the FlaB for inner reaction were: forward (220f), 5′-CAGACAACAGAGGGAAAT-3′; and reverse (824r), 5′-TCAAGTCTATTTTGGAAAGCACC-3′. PCRs was performed as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 50°C for 45 seconds, and elongation at 72°C for 1 minutes. The amplification product of 604 bp was analyzed after electrophoresis using a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

6. Sequence and phylogenetic analysis

The amplified PCR products were transported to Cosmogenetech (Daejeon city, Korea) for sequencing using an ABI 3730XL DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA). The nucleotide sequences were aligned via ClustalW to a reference sequence obtained from the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) database and phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the MEGA6 program (http://megasoftware.net). A neighbor-joining tree with 1,000 bootstrap replicates was constructed using the Kimura 2-parameter model.

The nucleotide sequences in this study were deposited into GenBank and were assigned the following accession numbers: Rickettsia species 45 sequences (MK283930-965, MK283970-MK283977, and MK283979), Anaplasma species 3 sequences (MK283923 and MK283923), and Borrelia species 9 sequences (MK283896-904).

7. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens

During the study period, the prevalence of tick-borne pathogens was calculated by (minimum positive rate = detected pools/collected ticks). The minimum positive rate for the pooled ticks refers to the number of positive pools per total number of ticks. It was assumed that each tick positive pool contained only 1 infected tick.

8. Cross-sectional study

To understand the seasonal variation of tick species and the risk factors associated with Rickettsia species, a cross-sectional study was conducted. The odds ratio was calculated for the presence of ticks and a significant prevalence rate was assumed when p < 0.05 which was incorporated into a logistic regression model using SPSS software Version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

1. Distribution of the field ticks

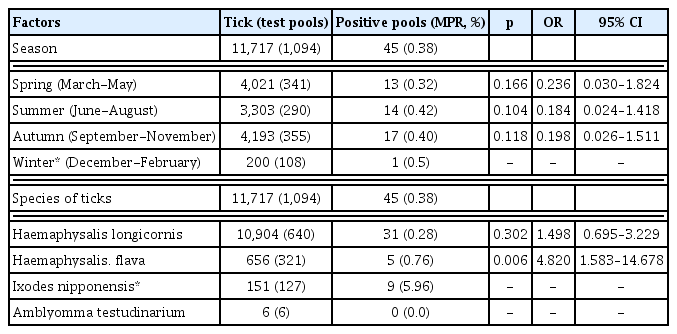

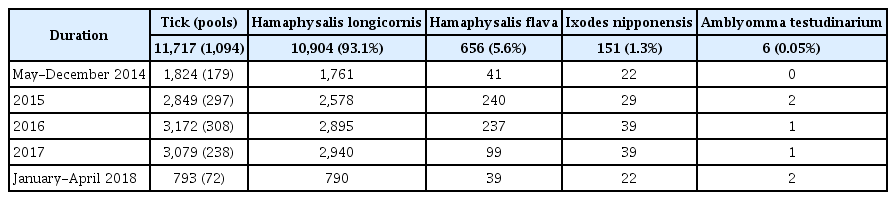

During the study period there were 11,717 ticks, including 4 species, collected. H. longicornis was the most common species (n = 10,904, 93.1%), followed by H. flava (n = 656, 5.6%), I. nipponensis (n = 151, 1.3%), and Amblyomma testudinarium (6, 0.05%; Table 1). The total number of tested pools was 1,094. There were 179 pools tested between May and December 2014, followed by 297 pools in 2015, 308 pools in 2016, 238 pools in 2017, and 72 pools between January and April 2018 (Table 1). The ticks were collected throughout the year and were most prevalent in April and September (Figure 1).

Seasonal variation of species detected in field ticks collected in the Gwang-ju metropolitan area, South Korea (May 2014–April 2018).

2. Detection of Rickettsia species

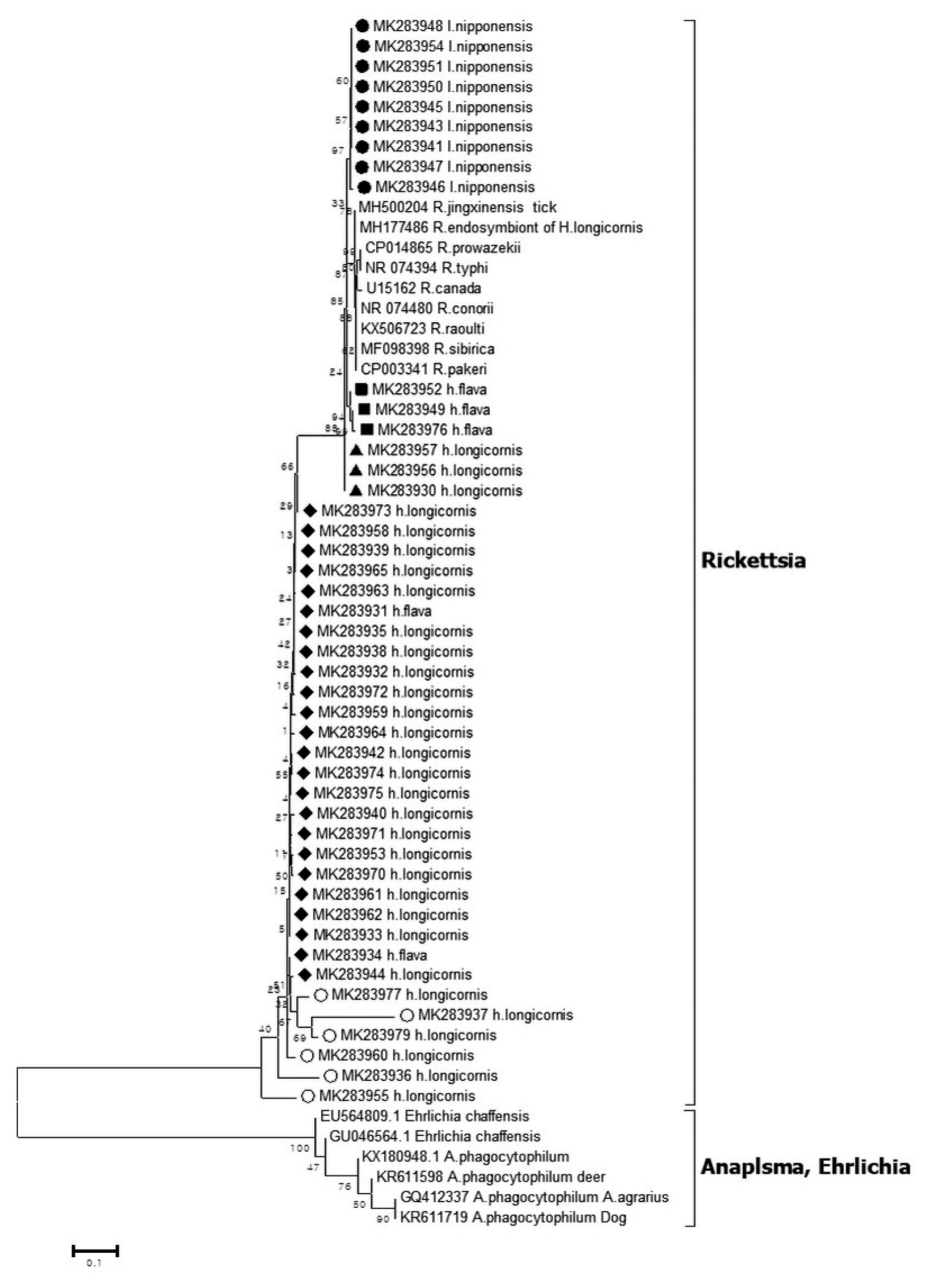

Out of the 1,094 pools tested, 45 pools were positive for Rickettsia 16S rRNA coding gene as revealed by phylogenetic analysis (Figure 2). Nine sequences (MK283941, MK283943, MK283945-948, MK283950, MK283951, and MK283954) detected from I. nipponensis were 94.3%–94.4% homologous to the Cadidatus R. jingxinensis sequence (accession no. MH500204). Three sequences (MK283949, MK283952, and MK283976) detected from H. flava were 93.5%, 94.0%, and 94.5% homologous to the Ca. R. jingxinensis sequence (accession no. MH500204). Three sequences (MK283930, MK283956, and MK283957) detected from H. longicornis were 95.6% homologous to the Ca. R. jingxinensis sequence (accession no. MH500204). Twenty-four sequences (MK283931-935, MK283938-940, MK283942, MK283944, MK283953, MK283958, MK283939, MK283961-965, and MK283970-975) detected from 22 pools of H. longicornis and 2 pools of H. flava were 81.7%–85.8% homologous to the Ca. R. jingxinensis sequence (accession no. MH500204). Six sequences (MK283936, MK283937, MK283955, MK283960, MK283977, and MK283979) detected from H. longicornis were 61.0–82.6% homologous to the Ca. R. jingxinensis sequence (accession no.: MH500204).

Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequence of Rickettsia species detected in the field ticks collected in South Korea, from May 2014-April 2018. The phylogenetic tree was constructed through the neighbor-joining method with the Kimura two-parameter model (bootstrap 1,000) using MEGA 6.0. The GenBank accession numbers of each sequence of Rickettsia species and Anaplasma species are indicated.

3. Detection of Anaplasma phagocytopylum

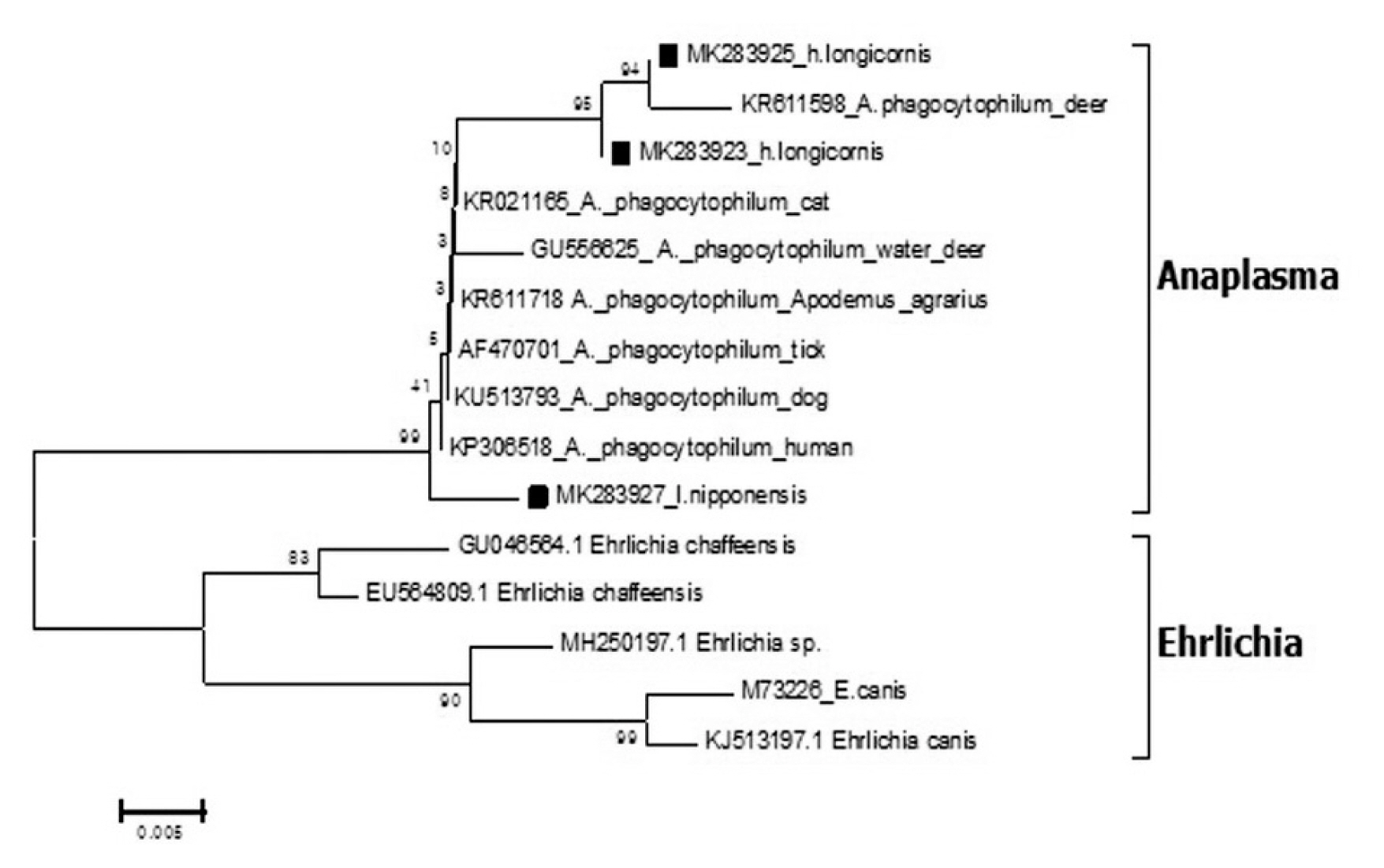

Out of the 1,094 pools tested, 3 pools were positive for Anaplasma 16S rRNA coding gene by phylogenetic analysis (Figure 3). Three sequences (MK283923, MK283925, and MK283927) were detected from 2 pools of H. longicornis and 1 pool of I. nipponensis was detected with 95.6%, 99.4%, and 99.6% homologous to the A. phagocytopylum sequence (accession no. AF470701), respectively.

Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequence of Anaplasma species detected in the field ticks collected in South Korea, from May 2014-April 2018. The phylogenetic tree was constructed through the neighbor-joining method with the Kimura two-parameter model (bootstrap 1,000) using MEGA 6.0. The GenBank accession numbers of each sequence of Anaplasma phagocytopylum and Ehrlichia species are indicated.

4. Detection of Borrelia species

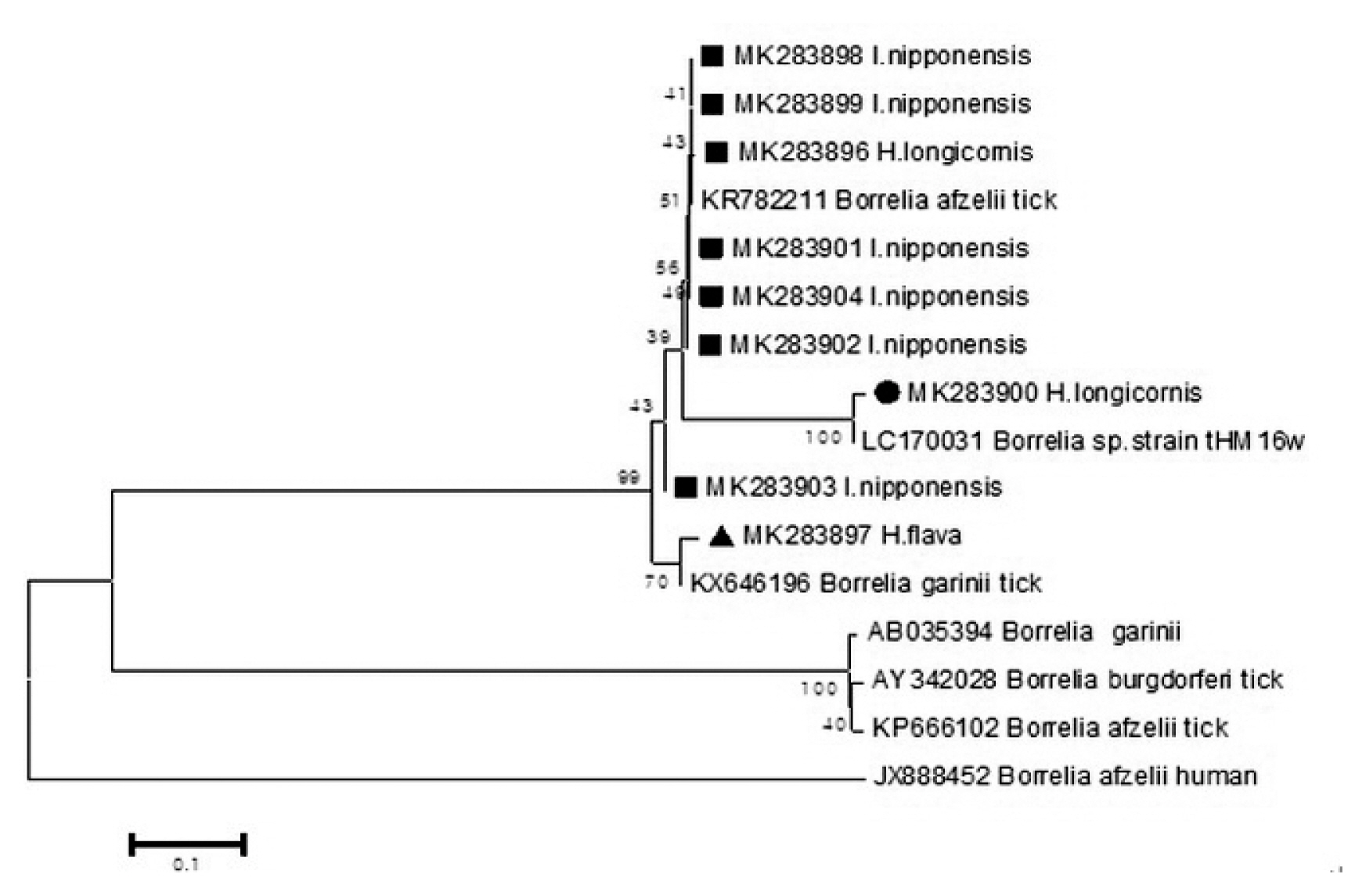

Out of the 1,094 pools tested, 9 pools were positive for Borrelia species (Figure 4) by phylogenetic analysis using the Fla coding gene. Two sequences (MK283896, MK283900) were detected from 2 pools of H. longicornis. Six sequences (MK283898, MK283899, MK283901, MK283902, MK283903, MK283904) detected from 6 pools of I. nipponensis were similar to the Borrelia species). A sequence (MK283897) detected from 1 pool of H. flava was close to the Borrelia species.

Phylogenetic tree based on the Fla gene sequence of Borrelia species detected in the field ticks collected in South Korea, from May 2014-April 2018. The phylogenetic tree was conducted through the neighbor-joining method with the Kimura two-parameter model (bootstrap 1,000) using MEGA 6.0. GenBank accession numbers of Borrelia species are indicated for each sequence

5. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens

Out of the 11,717 ticks (1,094 pools), 45 pools (0.38%) were positive for Rickettsia species, 3 pools (0.02%) were positive for A. phagocytophilum, and 9 pools (0.07%) were positive for Borrelia species (Table 2). Out of 640 pools containing 10,904 H. longicornis ticks, 31 pools (0.28%) were positive for Rickettsia species, 2 pools (0.02%) were positive for A. phagocytophilum, and 2 pools (< 0.01%) were positive for Borrelia species. Out of 321 pools containing 656 H. flava ticks, 5 pools (0.76%) were positive for Rickettsia species, and 1 pool was positive (0.15%) for Borrelia species. Out of 127 pools containing 151 I. nipponensis ticks, 9 pools (5.96%) were positive for Rickettsia species, 6 pools (3.97%) were positive for Borrelia species, and 1 pool (0.66%) was positive for A. phagocytophlum.

6. Co-infection

In 1 pool of H. flava, Rickettsia species (MK283934) and B. garinii (MK283897) were confirmed by PCR. The pool consisted of 1 H. flava tick.

7. Cross-sectional study for Rickettsia species

To assess the transmission risk factors (seasonal variation and tick species) for Rickettsia species, 11,717 ticks (1,094 pools) were analyzed. The distribution of the Rickettsia species by seasonal variation did not show a significant difference between Spring, Summer, and Autumn, using winter as the reference season (Table 3). Among the different species of ticks, the H. flava-carrying ticks were the most frequently detected in Gwang-ju, South Korea, from May 2014 to April 2018 (odds ratio 4.820, 95% CI: 1.583–14.678, p = 0.006; Table 3).

Discussion

It is essential to investigate the epidemiological characteristics of field tick-borne pathogens in order to establish preventive measures against tick-borne infections in humans. In the Gwangju metropolitan area, there is limited epidemiology data of ticks. In particular, ticks are affected by changes in climate and habitat. There are limitations in identifying trends in the tick populations and in predicting infections through short-term distribution surveys.

In a 4-year survey, out of the 11,717 ticks, H. longicornis was the most dominant species [10,904 (93.1 %);Table 1]. H. longicornis was reported to be a dominant species in Korea in earlier studies reported in 2013 and 2017, which included data of field ticks collected for 2 years [2,4]. H. longicornis is considered to be an important species of tick-borne diseases in Korea. Based on the annual distribution pattern over 4-years, the tick population increased in March and peaked in April and September (Figure 1), similar to previously published data by Chong et al [2]. The data in this current study showed that ticks exist in the winter months (December to February) as well. However, since there have been no earlier attempts to collect ticks in the Winter season in Korea, this observation is a novel finding. The seasons for tick-borne diseases in Korea is anticipated to begin in Spring and last until early Autumn when the tick population increases. Thus, special attention is required in these seasons and especially when the tick population reaches its peak in April and September.

The Rickettsia species sequences for 16S rRNA detected in the ticks (Figure 2) showed homology with the Ca. R. jingxinenesis (MH500204) sequence and was reported in ticks from China. In Korea, Rickettsia japonica was reported in a 16S rRNA-based analysis which was different to the data observed in this study [7], but it is possible that the pool of this study consisted of more than 1 tick, and the sequences were mixed. The Rickettsia species sequence detected in the ticks showed tick species-wise differences. The sequences in I. nipponensis (MK283941, MK283943, MK283945-948, MK283950, MK283951, and MK283954) and H. flava (MK283949, MK283952, and MK283976) showed a tendency to be different in the sequence of H. longicornis (Figure 2). By species of tick, differences in the Rickettsia species have previously been reported in Korea and abroad. In particular, Rickettsia monacensis was only reported in Ixodes species [13,19].

The A. phagocytophilum sequences for 16S rRNA detected in the ticks (Figure 3) showed homology with the A. phagocytophilum (AF470701) sequence and was reported in ticks from Korea [12]. Similar to the study by Kim et al [12], this current study confirmed the presence of A. phagocytophilum in H. longicornis. However, unlike the study of Kim et al [12], detection of I. nipponensis showed a 99.6% homology with A. phagocytophilum.

The sequences (MK283896, MK283898, MK283899, MK283901, MK283902, MK283904, MK283897) for Fla detected in the ticks were close to Borrelia species (Figure 4. In Korea, B. afzelii and B. garinii are known to be responsible for causing Lyme disease [20,21], and were detected in this current study. The sequence (MK283900) of H. longicornis showed high concurrency with a Borrelia species strain_(tHM16w) reported in ticks from Japan [22]. Sequences of bacteria detected in ticks identified in Europe and Japan, are also detected in Korea.

In 1 pool (H. flava), a co-infection of Rickettsia species (MK283934) and B. garinii (MK283897) was confirmed. Many cases of co-infection in ticks have been reported worldwide [23–25]. The pathogen content of ticks was not significantly high in any season (Table 3) and was consistent throughout the year. This implied that the ticks could transmit pathogens at any time of the year. Since there are no reports of pathogen surveys in ticks throughout the whole year in Korea, our research is likely to be meaningful in predicting the prevalence of tick-borne diseases.

In conclusion, due attention should be paid to preventing tick-borne infections in humans while performing outdoor activities in the Spring and Autumn, particularly in places where the prevalence of ticks is high. Monthly data were collected to provide reliable information on the seasonal variation of tick numbers and tick-borne pathogens. In all the collected species, the presence of pathogens was demonstrated and in particular, the presence of Rickettsia species and H. flava warrants caution. To prepare for tick-borne disease epidemics, the seasonal variation in the numbers of ticks should be studied and the pathogen content of ticks should be continuously monitored.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Health and Environment Research Institute of Gwang-ju, Korea.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.